When Genetic Screening Seems to Work and Ethics Still Fails

Why the real lesson of the sperm donor cancer case is not genetics, but scale

What happened

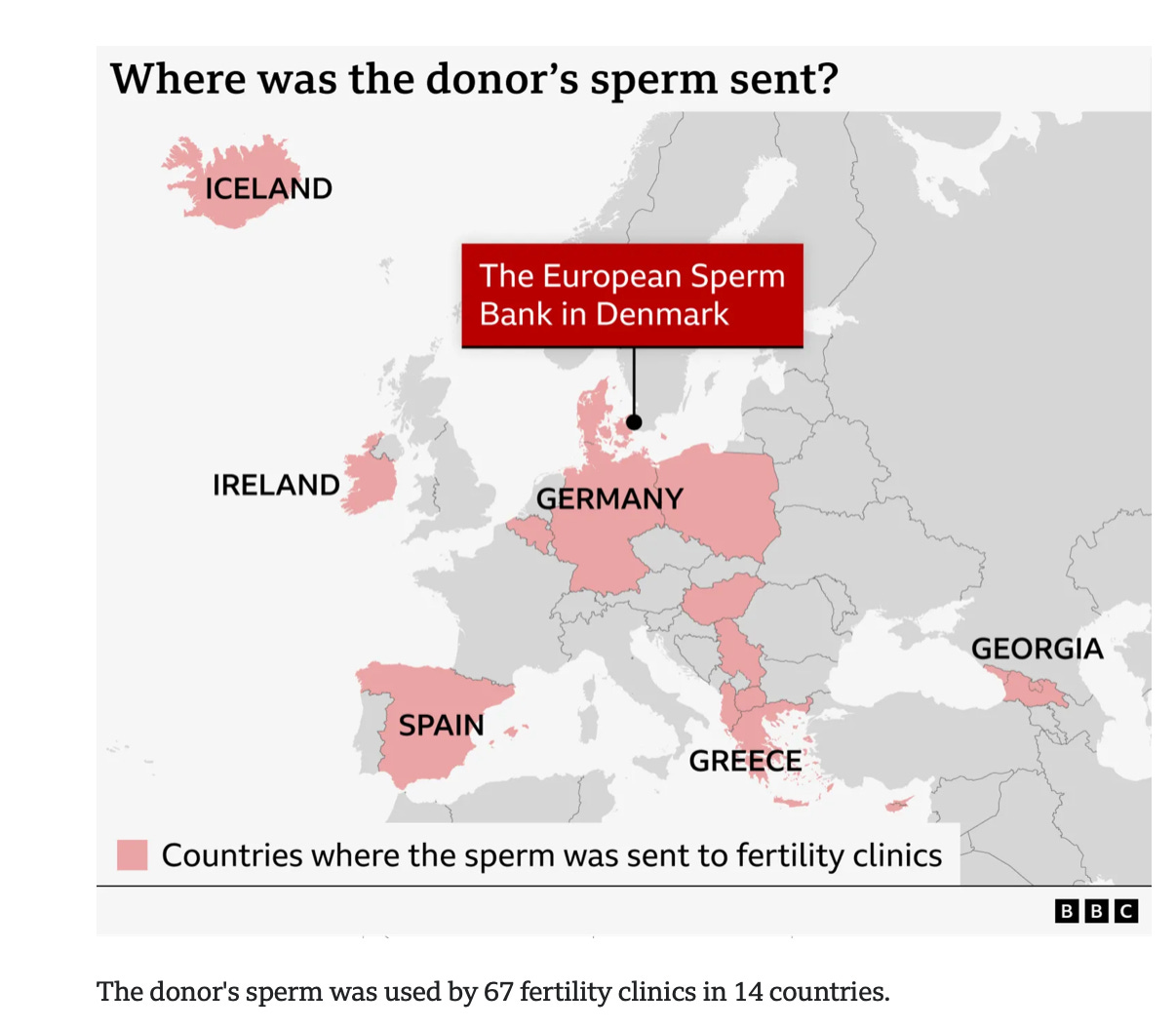

In late 2025, an international investigation revealed that sperm from a single donor had been used to conceive at least 197 children across Europe. The donor sperm came from a sperm bank in Denmark. Years later, some of those children were diagnosed with cancer. Several died. Many more now live under lifelong medical surveillance.

The sperm had been sold to 14 countries:

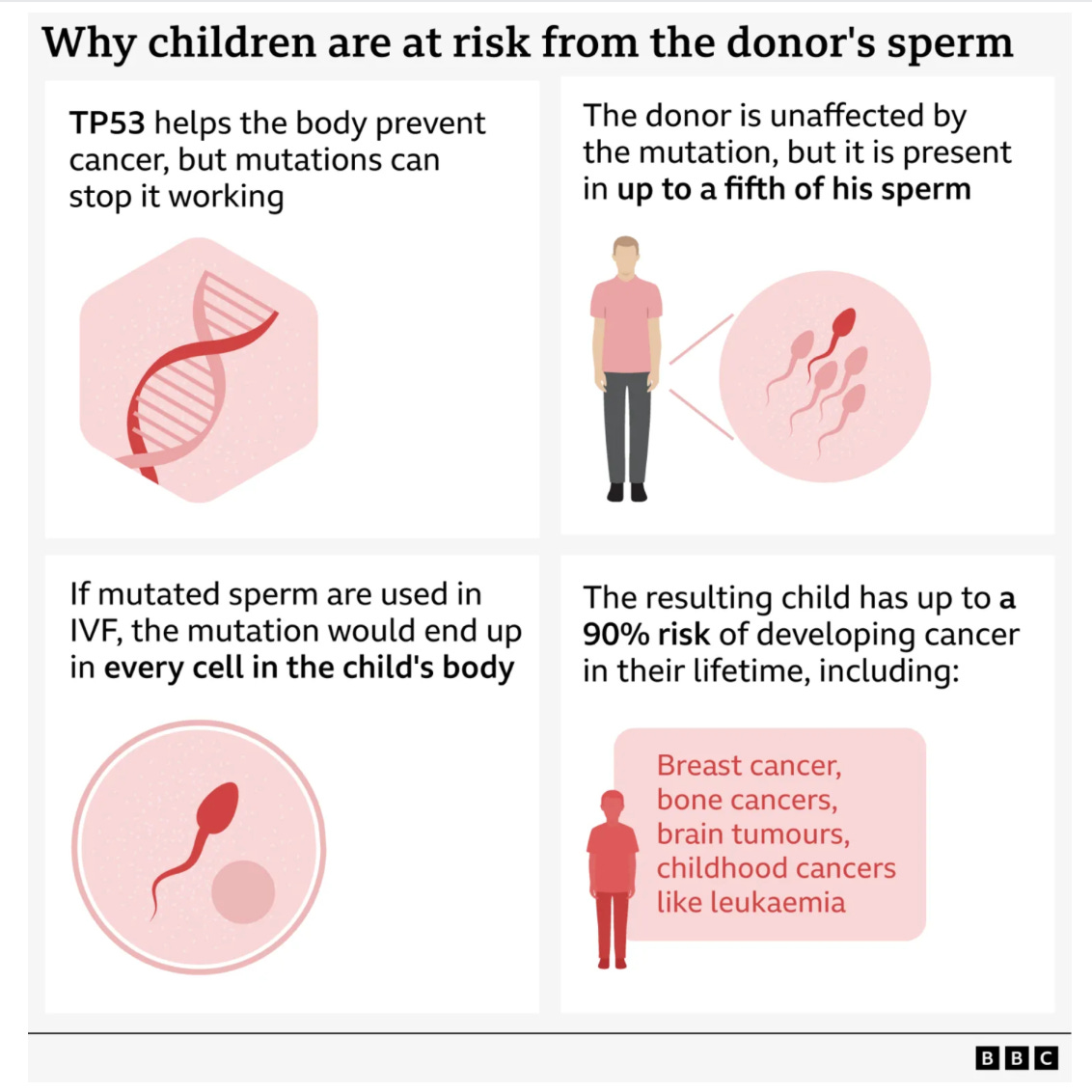

The underlying diagnosis was Li-Fraumeni syndrome, caused by a pathogenic mutation in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene. This condition carries an exceptionally high lifetime risk of cancer, often beginning in childhood and involving multiple organs. What made this case especially troubling is that the donor himself was healthy. He passed all required screening at the time of donation. The mutation was present only in a portion of his sperm due to germline mosaicism, a biological phenomenon that routine testing could not detect then and often cannot detect even now.

Once the mutation was discovered, the donor was blocked and families were notified. But by that point, the harm had already propagated across countries, clinics, and years. This was not a story of fraud or bad faith. It was a story of medicine operating at scale while ethics lagged behind.

Check out a proposed way to check sperms and eggs for screening issues

What exactly was diagnosed, and why it matters

Li-Fraumeni syndrome is not a mild or theoretical risk. It is one of the most penetrant cancer predisposition syndromes known. Children who inherit the TP53 mutation face a dramatically elevated risk of leukemia, brain tumors, sarcomas, and other malignancies. Adults, especially women, face high risks of early breast cancer and additional cancers over a lifetime.

Crucially, the donor did not have the mutation in most of his body. Standard blood testing would not reliably identify mosaicism limited to germ cells. This is not a loophole. It is a known biological limitation.

That fact matters ethically. The failure here was not that clinicians or sperm banks missed something they reasonably could have detected. The failure was assuming that because screening is incomplete, it is therefore sufficient to expose hundreds of future children to the same undetectable risk.

Historical context

Li-Fraumeni syndrome was first described in 1969 by Frederick Li and Joseph Fraumeni, who identified families with striking clusters of early-onset cancers across generations. The genetic basis was not known at that time.

The causative link to pathogenic variants in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene was established only in 1990, when TP53 was identified as a key cancer-predisposition gene.

Clinical genetic testing for TP53 became available in the mid-to-late 1990s, initially limited to research settings and families with strong cancer histories. Broader clinical screening and inclusion of TP53 on multigene panels expanded gradually in the 2000s and 2010s, as sequencing technologies improved. Even today, detection remains incomplete for certain biological scenarios, including germline mosaicism, which limits the ability of screening to fully prevent transmission.

Screening has evolved, but uncertainty has not disappeared

Over the past two decades, donor screening has expanded dramatically. Twenty years ago, screening focused on infectious diseases, basic medical history, and limited genetic assessment. Family history was central, but molecular testing was narrow and selective.

Ten years ago, expanded carrier screening became more common, primarily targeting autosomal recessive childhood conditions. These panels were designed to reduce the risk of severe pediatric disease, not to identify dominant cancer syndromes with variable onset and expression.

Today, many donor programs test hundreds of genes. Traceability has improved. Reporting obligations are stronger. Genetic technology is far more sophisticated. Yet even now, screening cannot detect all clinically meaningful risk.

There are thousands of rare genetic conditions, many incompletely characterized. New pathogenic variants are identified every year. Some arise de novo. Others, like mosaic mutations, may not be present in the tissues we test. Genetics remains probabilistic, not deterministic.

This is the ethical pivot point. Medicine has rightly invested in better screening. But better screening does not eliminate uncertainty. It only narrows it.

Whose genetics are we really screening?

Public reaction to cases like this often assumes that donor conception should be “genetically safer” than natural conception. That assumption deserves scrutiny.

In routine obstetric care, most pregnant women and their partners are not screened for cancer predisposition genes such as TP53. Carrier screening is typically limited to recessive conditions relevant to reproductive risk. Broad oncogenetic testing is not standard unless there is a strong family history or clinical indication.

In other words, the vast majority of children conceived worldwide are born to parents whose cancer genetics have never been tested.

By that measure, donor sperm is often screened more extensively than most biological fathers.

This is uncomfortable, but important. The ethical problem is not that donor screening falls short of some imagined genetic perfection. The ethical problem is that donor conception introduces systemic amplification of risk.

One undetected mutation in one natural conception affects one family. One undetected mutation in a widely used donor affects dozens or hundreds of families.

Scale changes the moral equation

Medicine is accustomed to thinking in probabilities. Ethics must also think in multiplication.

When a rare, unavoidable uncertainty is repeated hundreds of times, it stops being a background risk and becomes a foreseeable harm. This is not a genetic insight. It is a moral one.

The same uncertainty that is ethically tolerable once becomes ethically unacceptable at scale.

This is why limits on donor use are not merely administrative or social safeguards. They are instruments of preventive ethics. They acknowledge that uncertainty cannot be eliminated, but harm can be contained.

Professional responsibility beyond compliance

No clinician involved in this case acted outside existing regulations. That fact should trouble us, not reassure us.

Professional responsibility is not exhausted by regulatory compliance. It requires judgment about how systems behave over time, across borders, and under commercial pressure.

Clinicians, fertility centers, and professional societies have an obligation to ask uncomfortable questions. How many families has this donor already been used for? In how many countries? What happens when adverse outcomes emerge years later? Who is accountable when harm crosses jurisdictions?

Ethics demands that we confront these questions before tragedy forces the issue.

The lesson we should not miss

This case was not caused by inadequate genetics. It was caused by ethical minimalism in the face of scale.

Screening will continue to improve. Genomic tools will become more powerful. But uncertainty will never disappear. When medicine helps create life under conditions of uncertainty, ethics must step in where technology cannot.

The core lesson is stark and simple. When rare risks are multiplied at industrial scale, professional responsibility requires limits, transparency, and restraint. Preventive ethics is not about predicting every harm. It is about refusing to let uncertainty become a mass casualty event.

If this case teaches us anything, it is that in reproductive medicine, how often we use a donor can matter as much as how well we screen one.

Check out a proposed way to check sperms and eggs for screening issues

Are recipients fully informed of what was tested, and what was not?

One of the most ethically uncomfortable aspects of donor conception is how incomplete informed consent often is, even when all legal requirements are met.

Most recipients of sperm or egg donation are told that donors have been “extensively screened” or “medically cleared.” What they are far less often given is a precise, itemized explanation of what was actually tested, what was not tested, and what cannot be tested with current science.

In many settings, recipients receive a summary rather than a specification. They are informed that infectious disease screening was performed, that carrier screening was done, and that family history was reviewed. They are rarely told which genes were included, which were excluded, what the detection limits are, or what forms of genetic risk remain fundamentally unknowable.

This matters ethically because phrases like “extensive screening” invite false reassurance. They imply completeness where none exists.

What are the requirements today?

Current requirements for donor screening vary by country but generally include:

Mandatory infectious disease testing.

Detailed personal and family medical history.

Genetic carrier screening for selected inherited conditions, usually autosomal recessive diseases associated with severe childhood outcomes.

Periodic updates and re-review if new information emerges.

What they generally do not require is:

Universal screening for dominant cancer predisposition syndromes.

Testing capable of detecting germline mosaicism.

Ongoing genomic reanalysis as scientific knowledge evolves.

Harmonized international limits on donor usage.

Importantly, none of these omissions represent negligence. They reflect scientific limits, cost considerations, and the absence of clear consensus on how much genetic knowledge is ethically required before conception.

But ethical adequacy is not the same as technical feasibility.

Should recipients be told more than the law requires?

From an ethical standpoint, the answer is yes.

Informed consent is not a legal checkbox. It is a moral process. When patients are making decisions that affect not only themselves but future children, disclosure should prioritize understanding over reassurance.

Check out a proposed way to check sperms and eggs for screening issues

Recipients should reasonably be informed that:

Screening reduces risk but does not eliminate it.

Thousands of rare genetic conditions exist that are not routinely screened.

Some serious conditions arise from mutations that cannot be detected in blood testing.

The largest remaining risk is not test failure, but scale, meaning how many times the same donor is used.

Recipents should obtain all copies of screening results. Original copies, not summaries. Then they can look up the resuts by attaching them to a GenAI program like ChatGPT or Gemini and enter the following Prompt:

This does not require overwhelming patients with technical detail. It requires honesty about uncertainty.

The ethical asymmetry of donor conception

There is an ethical asymmetry at the heart of donor conception that clinicians often underappreciate.

In natural conception, genetic uncertainty is distributed randomly across the population. In donor conception, uncertainty is concentrated. The same unknown risk is repeated intentionally and systematically.

This is why consent standards should arguably be higher, not lower, for donor conception. Not because donor conception is unsafe, but because its structure amplifies the consequences of unavoidable uncertainty.

Yet current consent practices often focus on what has been tested rather than on what cannot be guaranteed. This imbalance shifts ethical burden from institutions to families, often without families realizing it.

Completeness is impossible. Candor is not.

No screening program, now or in the foreseeable future, can offer genetic certainty. Even whole-genome sequencing cannot predict penetrance, expression, or future discoveries. Pretending otherwise undermines trust.

The ethical obligation, therefore, is not completeness. It is candor.

Candor means acknowledging missing pieces. It means resisting marketing language that implies safety through thoroughness. It means explaining that donor screening is better than it used to be, better than most natural conception screening, and still fundamentally incomplete.

Most patients can tolerate uncertainty. What they struggle with is learning, years later, that uncertainty was minimized rather than explained.

The ethical bottom line

This case should not drive us toward unrealistic demands for perfect screening. It should drive us toward better disclosure, stricter limits on scale, and a more honest consent process.

Ethics does not demand that we eliminate all genetic risk. It demands that we do not multiply it silently.

When medicine helps create life using systems that magnify uncertainty, professional responsibility requires more than compliance. It requires transparency about limits, humility about knowledge, and restraint where repetition turns rare risk into foreseeable harm.

That is the ethical lesson we ignore at our peril.

Check out a proposed way to check sperms and eggs for screening issues

Scale is the one variable that can and should be immediately addressed. Consensus already exists internationally on many conditions to be screened e.g. infectious diseases. The ART/Fertility community should limit any given donor to some number which would minimize and therefore somewhat mitigate this type of low probability but difficult to diagnose/predict risk