Your Risk Is Not “1 in 384.” It’s a Story About You and Your Baby

The Human Factor - Obstetrics keeps throwing scary numbers at pregnant women. We need to stop performing with statistics and start telling the truth.

What the Numbers Really Mean

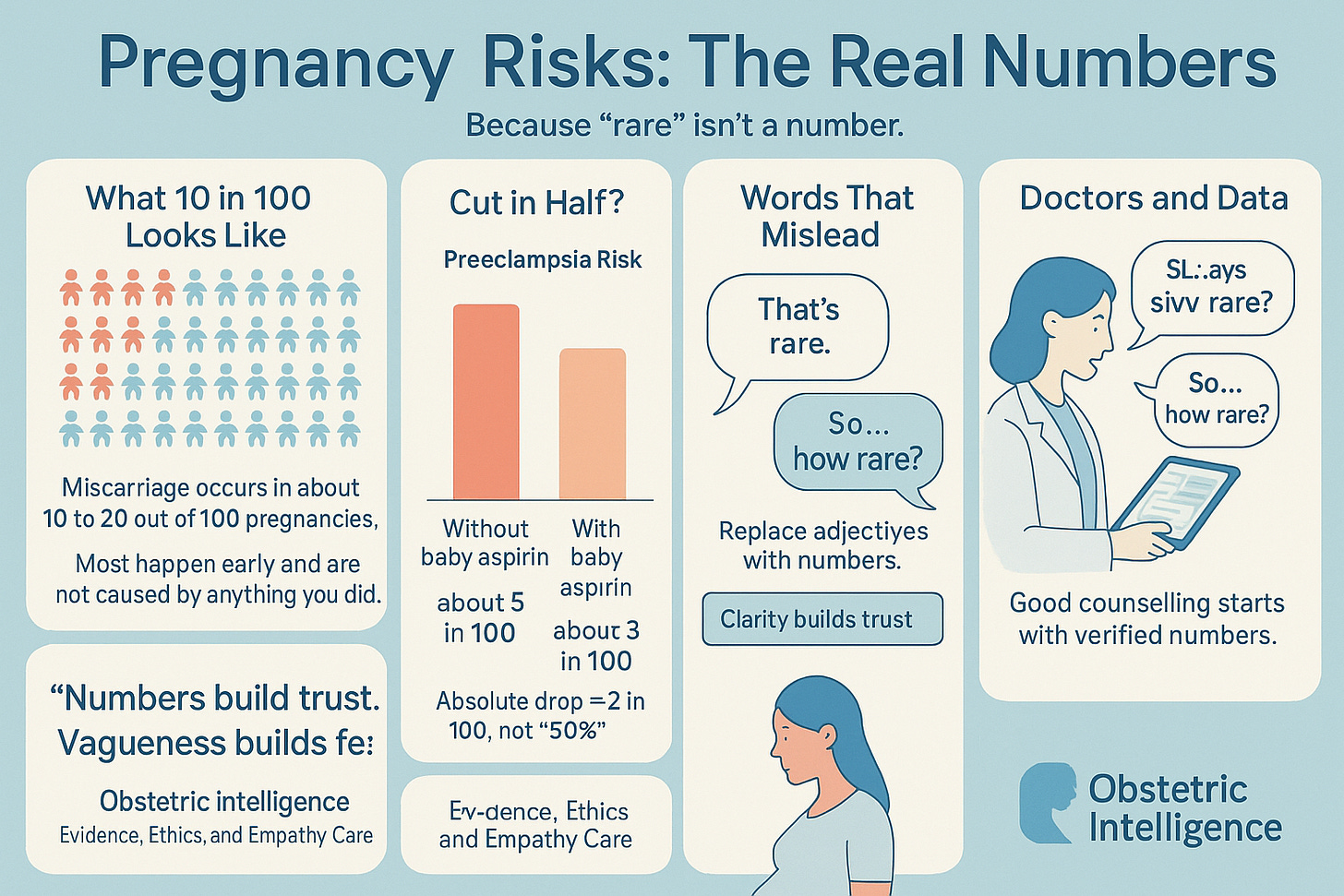

Almost every pregnant woman hears numbers in prenatal care. “Your chance of Down syndrome is 1 in 384.” “The risk of preeclampsia goes down 50 percent if you take aspirin.” “Stillbirth is rare.” These sound precise but are not clear, not honest, and not built for how real people process risk -with emotion first and math second. The problem is not women’s numeracy; it is the medical system’s habit of choosing the wrong numbers and the wrong way to say them.

The “1 in X” Trap

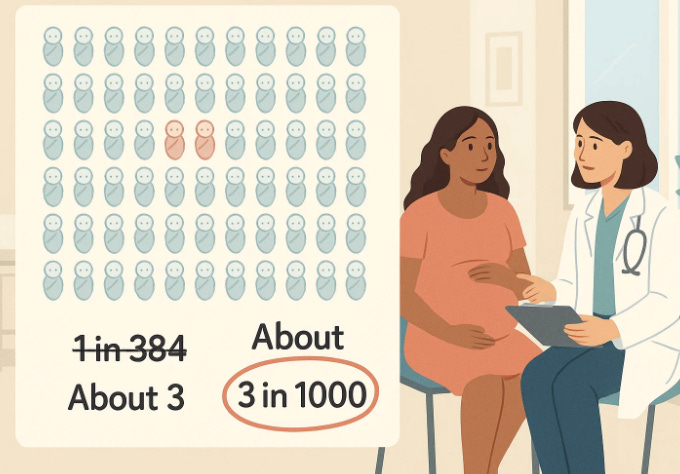

A patient sits across from me, trembling after hearing her baby has “a 1 in 112 chance” of a chromosomal issue. To her, that means almost certain. She is not wrong to feel that way. In one study of 633 pregnant women, 73 percent correctly identified which risk was higher when framed as “8.9 per 1000 vs 2.6 per 1000.” Only 56 percent got it right when told “1 in 112 vs 1 in 384.” The “1 in X” format distorts perception and makes risk feel larger.

We can fix this immediately. Use one consistent denominator. Say “about 9 in 1000 versus 3 in 1000,” or “about 1 percent versus 0.3 percent.” Informed consent begins when comprehension does.

Stop Calling Things “Rare” or “High Risk” Without Numbers

When clinicians say a condition is “rare,” patients guess anywhere from 0 to 80 percent. “Common” means anywhere from 10 to 100 percent. Those words are meaningless. Yet obstetrics relies on them. “High risk pregnancy.” “Rare complication.” Without numbers, such labels cause anxiety, guilt, and defensive choices. A simple fix: say “about 4 in 100” or “less than 1 in 1000.” Patients prefer numeric or mixed formats over words alone.

The Relative-Risk Mirage

You’ve heard it: “Baby aspirin cuts the risk of preeclampsia in half.” It sounds dramatic, but “in half” hides the truth. If the risk drops from 15 percent to 8 percent, that’s a meaningful 7-point difference -not magic. Across 17 studies, relative terms like “33 percent reduction” made treatments seem more effective and more compelling than when absolute numbers were shown.

Even guideline writers fall for it: benefits in relative terms, harms in absolute ones. That framing exaggerates help and minimizes harm. It is not statistics; it is marketing.

Show the Whole Picture

When we display only the numerator -the bad outcomes - risk looks enormous. But when we show both numerator and denominator, perception balances. Visuals that include all 100 cases, with a few highlighted, help patients grasp proportion. Obstetrics often dramatizes the numerator. We need to re-draw the picture.

Give Numbers Context

Pregnant women see countless lab values - platelets, glucose, blood pressure -without translation. When numbers are shown with clear thresholds, patients worry less about near-normal results yet still respond appropriately to danger. For preeclampsia, that means explaining which blood pressure is “watch,” which is “act.” Context turns data into guidance.

Five Rules for Better Risk Talk

Always give a number. Never say “rare” or “high risk” without one.

Use one denominator. Percent or per 1000, not “1 in X.”

Speak in absolutes. “From 15 to 8 percent,” not “cuts in half.”

Show scale. Include all 100 outcomes, not just the tragic few.

Mark thresholds. Tell patients when clinicians truly act.

Doctors Must Know Their Numbers — Or Know How to Find Them

One of the quiet failures in modern obstetrics is how many conversations begin with confidence but without data. “It’s rare.” “That’s not a big risk.” “Aspirin helps.” Too often, clinicians rely on memory, habit, or vague impressions of risk rather than current evidence. But patients deserve precision. When we tell a woman that her chance of a complication is “low,” we are making a claim about reality. That claim should be supported by numbers we can verify.

In a world where accurate data are seconds away, saying “I’m not sure” is no longer a weakness - it is professionalism. Artificial intelligence tools can instantly access the latest research, guidelines, and population-level probabilities. The point is not to replace the physician’s judgment but to enrich it. A clinician who asks an AI or database for “current rates of preeclampsia by age and parity” before walking into the room will speak with clarity and humility instead of approximation and authority.

Here’s a simple example of how to use it. You could open your AI assistant and type:

Prompt: “Always give a number. What is the current absolute risk of preeclampsia in first pregnancies for women aged 30 to 34 in the United States, and how does low-dose aspirin change that?”

Within seconds, you’ll have precise, evidence-based numbers to discuss. You can then translate them: “Your chance of preeclampsia is about 5 in 100. If you take baby aspirin daily, it drops to around 3 in 100.” That is what informed consent sounds like.

Doctors should not fear numbers or technology. They should fear getting caught without either in front of a patient who deserves both.

Why This Is an Ethical Issue, Not a Soft Skill

When women misunderstand risk, informed consent collapses. Miscommunication about numbers is not harmless; it manipulates autonomy. Presenting relative benefits and hiding absolute harms is bias disguised as precision.

If we would speak differently to our own daughters—“about 3 in 1000,” “from 15 to 8 percent,” “if it reaches this number, we act”—then our current counseling is not ethical enough for someone else’s.

5 Risks Every Pregnant Woman Should Know — In Real Numbers and Real Words

Miscarriage – happens in about 10 to 20 in 100 pregnancies, mostly in the first trimester.

Usually caused by genetic problems in the embryo and not by anything you did.Ectopic pregnancy – about 1 to 2 in 100 pregnancies.

The embryo implants outside the uterus and needs urgent treatment to prevent internal bleeding.Gestational diabetes – affects about 6 to 9 in 100 women.

Can cause large babies and complications at birth if untreated, but controlled with diet or insulin it’s manageable.Preeclampsia – around 3 to 5 in 100 pregnancies.

A rise in blood pressure with organ stress that can harm mother and baby if not caught early.Preterm birth (before 37 weeks) – about 10 in 100 births.

Earlier delivery increases risk for breathing and feeding problems but most babies after 34 weeks do well.Stillbirth (after 20 weeks) – roughly 6 in 1000 births in the U.S.

Risk rises slightly after 40 weeks or with certain conditions like diabetes or hypertension.Placenta previa – about 1 in 200 pregnancies.

Placenta covers the cervix; usually requires cesarean delivery.Placental abruption – about 1 in 100 pregnancies.

Placenta separates too early, causing bleeding and requiring urgent care.Postpartum hemorrhage – about 3 to 5 in 100 births.

Excess bleeding after delivery; treatable but one of the top causes of maternal complications.Cesarean delivery – performed in about 32 in 100 U.S. births.

Sometimes planned, sometimes emergency; carries longer recovery and surgical risks.Vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) uterine rupture – about 5 in 1000 attempts.

Serious but uncommon; safest in well-equipped hospitals.Infection during pregnancy (chorioamnionitis, urinary tract, etc.) – about 10 in 100 pregnancies.

Usually mild but important to treat to protect both mother and baby.Anemia – about 15 to 25 in 100 pregnancies.

Low iron can cause fatigue and increase need for transfusion at birth.Group B strep infection in newborn – about 1 in 2000 births without antibiotics.

Simple screening and antibiotics during labor prevent nearly all cases.Preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (water breaks early) – about 3 in 100 pregnancies.

Increases infection and early birth risk; requires hospital monitoring.Multiple pregnancy (twins or more) – about 3 in 100 pregnancies.

Higher risk for preterm birth, anemia, and preeclampsia.Fetal growth restriction (baby smaller than expected) – about 5 to 10 in 100 pregnancies.

Often related to placenta function; requires close monitoring and timed delivery.Birth defects overall – about 3 in 100 babies.

Most are mild; only about 1 in 100 are serious or life-threatening.Gestational hypertension (high blood pressure without protein) – about 6 in 100 pregnancies.

Can progress to preeclampsia, so regular checks are key.Amniotic fluid problems (too much or too little) – about 1 to 2 in 100 pregnancies.

Usually monitored with ultrasound and managed with timing of delivery.Postpartum depression – about 10 to 15 in 100 mothers.

A real and treatable condition; needs early screening and support.Thromboembolism (blood clots) – about 1 in 1000 pregnancies.

Pregnancy increases clotting; risk is higher after cesarean or prolonged rest.Preterm preeclampsia-related complications for the baby – about 1 to 2 in 100 births.

Can cause low birth weight and NICU stay but good long-term outcomes with modern care.Rh incompatibility (untreated) – less than 1 in 1000 births with modern prevention.

Easily prevented with Rh-immune globulin injections.Maternal death (U.S.) – about 2 in 10,000 births.

Rare but still too high; main causes are hemorrhage, hypertension, and heart disease.

How to Use This List

Each number is a starting point, not a sentence. Ask your clinician:

“Which of these apply to me?”

“What are my actual odds?”

“How can I lower them?”

And when you ask, expect a number. If your doctor says “rare” or “low,” try this line:

“Could you give me the number, please? About how many women out of 100 does this happen to?”

That single question can turn fear into understanding—and guesswork into partnership.

What Daniel Kahneman Would Say About All This

Daniel Kahneman was a psychologist, not a physician, but his ideas changed the way doctors should think. He won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2002 for showing that human beings are not rational calculators of probability. We make decisions through emotion, shortcuts, and mental habits he called heuristics.

His research with Amos Tversky proved that how a number is framed matters more than the number itself. Say “a 90 percent survival rate” instead of “a 10 percent death rate,” and people make different choices.

If Kahneman sat in a prenatal counseling room, he would not be surprised by how “1 in 384” terrifies women or how “cuts the risk in half” distorts decisions. He would say that obstetrics is a perfect laboratory for cognitive bias—where uncertainty, emotion, and stakes are all at their highest. He would tell us that numbers are not neutral; they carry emotional weight, tone, and power.

Kahneman would likely remind us that the solution is not to make patients “more rational” but to design communication that respects how humans actually think. In pregnancy, that means showing the whole picture, speaking in absolute terms, and grounding every statistic in empathy.

The lesson is simple: if we want truly informed consent, we must learn to speak both languages—numbers and feelings—with equal fluency.