Why U.S. maternal mortality is so much worse than Europe’s

What fragmented care, social inequity, and policy neglect reveal about the American maternity system.

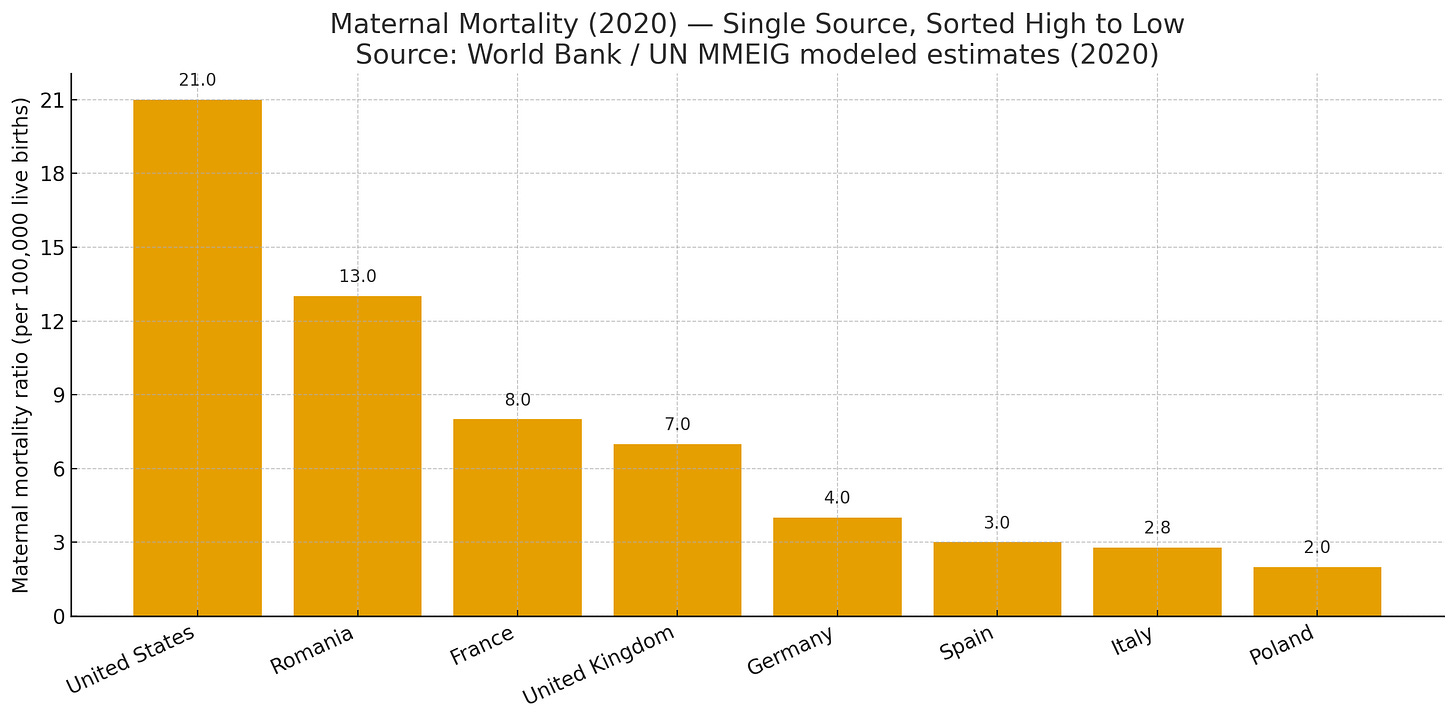

Start with the numbers. In 2023, the United States recorded about 18.6 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, down from 22.3 in 2022, yet still very high for a wealthy nation. Black mothers faced much higher risk than White mothers. Europe’s rich countries sit far lower. Recent OECD reporting shows single-digit rates in many European systems, with an OECD average near 11 in 2020 and countries like Norway and Iceland below 3. The gap is persistent and large. It is not a rounding error. It reflects how we design and finance care before, during, and after pregnancy.

Many people look for a simple villain. Some blame doctors and hospitals. Some blame racism. Some blame it on how we report maternal mortality in the US compared to Europe. Others point to obesity, older maternal age, cesareans, or patient behavior. These factors matter, but they are not the main story. The deeper drivers are system design, fragmented insurance, churn before and after birth, uneven access, and the way costs and hassles nudge families to delay care. Structural racism and the closing of local maternity units add more risk.

In other words, it is not one bad habit or one bad clinician. It is a predictable result of how we pay for and organize pregnancy care.

An explanation from Nobel prize winners

I like to introduce to you two Nobel prize winners in Economics who might explain this from an economic point of view.

Paul Krugman: Paul Krugman won the 2008 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for his work on trade theory and economic geography. He writes clearly about how insurance markets succeed or fail, which is the lens I use here.

Daniel Kahneman: Daniel Kahneman won the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for prospect theory, explaining how real people think about risk, loss, and time. His insights help explain why small costs and hassles lead to delayed pregnancy care.

The Krugman lens, applied to pregnancy

Paul Krugman’s health economics story is simple. Insurance markets need risk pooling and predictable subsidies, or they drift into a bad risk pool where prices rise, healthy people drop out, and outcomes get worse. Pregnancy care magnifies this dynamic. When coverage is fragmented or expensive, people delay visits, miss tests, and lose postpartum follow up. Delay in obstetrics is not just inconvenient. It is dangerous.

Europe avoids the spiral by funding maternity as a guaranteed benefit. The United States does not. Here, women churn between employer plans, Medicaid, exchanges, or no plan/no insurance at all. Deductibles reset. Networks change. Rural labor units close. Each friction point becomes a missed blood pressure check, a skipped diabetes screen, or an untreated mood disorder. Europe’s universal systems smooth those frictions, and that shows up in the mortality gap.

What Kahneman would say about our choices

Daniel Kahneman taught us that real humans do not decide like calculators. We rely on fast intuition, we fear losses more than we value gains, and we notice what is easy to recall.

Loss aversion. Large deductibles and surprise bills loom larger than unseen benefits. A copay today feels like a loss. A prevented eclampsia next month feels abstract. So families delay care. Universal coverage removes the near-term losses that drive harmful procrastination.

Present bias and hassle costs. Even small barriers, like prior authorization or a new portal login, shift behavior. In pregnancy, a two-week delay can move a patient past the ideal window for aspirin, anatomy scan, or glucose testing.

Availability bias. People overweigh vivid anecdotes. A friend’s story about a big hospital bill is more vivid than a statistic about reduced mortality. When universal coverage is the norm, the vivid story is a smooth prenatal path, not a financial scare.

Kahneman’s point is not to blame patients. It is to design systems that respect predictable human behavior. Universal maternity coverage does exactly that. It removes the losses and hassles that nudge people away from timely care.

The U.S. mechanics that convert insurance into mortality

Coverage churn in the perinatal year. Eligibility flips during pregnancy and again after birth. Postpartum coverage often ends just when cardiac, hypertensive, and mental health risks peak. Europe maintains coverage through the full year, which supports home blood pressure monitoring, lactation help, and depression care.

Cost sharing at the wrong moments. High deductibles and coinsurance make people think twice about calling or coming in. In obstetrics, waiting turns small problems into emergencies.

Administrative friction. Prior auth and narrow networks shift care later in time and farther in distance. Friction raises risk. Europe simplifies, bundles, and funds capacity so that teams can act early.

Underbuilt postpartum care. U.S. systems still struggle to guarantee visits by 1 to 3 weeks, to supply home cuffs, or to integrate mental health. France’s national data show mental health and cardiovascular disease as key drivers even within a universal model, which underscores how critical funded postpartum programs are everywhere.

What policy actually fixes quickly

Guarantee universal, first-dollar maternity coverage from pregnancy confirmation through 12 months postpartum, in every state. No deductibles for prenatal, delivery, or postpartum services, including mental health and home blood pressure devices.

Stabilize access. Pay to keep regional labor units open and integrate midwifery with reliable transfer protocols, so geography does not decide outcomes.

Strip friction from time-sensitive care. No prior auth for core pregnancy medications and ultrasounds. Publish simple criteria instead of denials.

Make early prevention the default. Automatic opt-in for aspirin when indicated, remote BP monitoring, and timely diabetes screening.

These are not moonshots. They are design choices that line up with human psychology and with the economics of risk pooling. Countries that fund universal coverage already harvest these gains, and their mortality rates show it. OECD

Our Professional Organizations

Professional groups like the AMA and, at times, ACOG often resist universal coverage for reasons that Kahneman would call loss aversion and status quo bias. Guaranteed public payment feels like a loss of pricing control, even if total volume and stability rise. Complex billing, multiple payers, and local negotiations are familiar, so the brain favors the current system. Krugman would add the market logic. By defending a fragmented payer mix, these groups preserve weak risk pooling and uneven subsidies, which reliably produce higher prices, coverage churn, and thin networks. In pregnancy, those market features convert into late entry to care, missed screening windows, and poor postpartum follow up. The opposition is not only ideological. It is financially rational within a fee-for-service world that rewards complexity and price variation. The public result is predictable. Fragmentation persists, friction at the point of care remains high, and maternal mortality stays above European levels. If we applied Kahneman’s insight, we would redesign incentives to lower perceived losses from universal coverage. If we applied Krugman’s, we would fix the risk pool with simple, first-dollar maternity benefits that keep healthy and high-risk patients in the same system from the first prenatal call through one year postpartum.

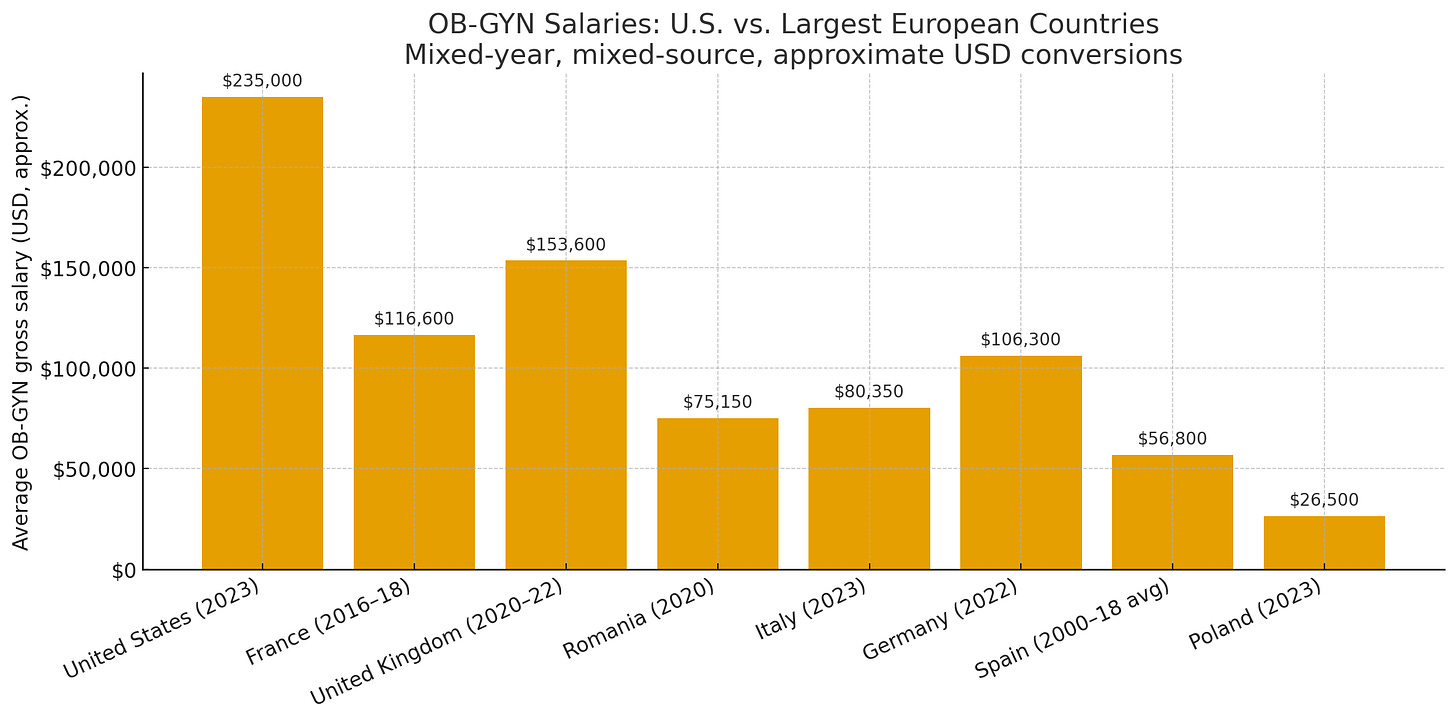

Average OB-GYN gross salaries for the same eight countries. These are illustrative, mixed-year estimates converted to USD; actual compensation varies by seniority, public vs private, overtime/guards, and region.

And remember the money context. Average OB-GYN pay in the United States sits around two to three times that of many European peers, often in the 200–300 thousand dollar range versus roughly 60–150 thousand dollars in large European systems, depending on country, seniority, and public versus private work. Kahneman would predict strong loss aversion when a policy threatens perceived income or pricing control, even if universal coverage would bring steadier payment and less administrative grind. Krugman would note that organizations defending a high-price, multi-payer market are effectively defending weak risk pooling. So while the AMA and ACOG often present themselves as pro-patient, their policy posture has usually been cautious to hostile toward universal, first-dollar national coverage. The result is that they help preserve a fragmented system that raises friction at the point of care, drives delayed prenatal and postpartum services, and, in aggregate, contributes to our higher maternal mortality compared with Europe.

Pregnancy Care Before and After Pregnancy: The Missing Link

The health of a pregnancy begins long before conception and extends long after delivery. Countries with the lowest maternal mortality rates treat pregnancy as a continuum of care, not a 9-month event. Pre-pregnancy health assessments, routine management of chronic conditions like hypertension, diabetes, and thyroid disease, and ready access to contraception are all funded as part of public maternity systems in most of Europe. In the United States, these steps are often fragmented by insurance status and geography. Many women lose coverage between adolescence and adulthood, regain it briefly through Medicaid during pregnancy, and lose it again just weeks after delivery. Each coverage gap creates a medical gap. A missed blood pressure check before conception becomes preeclampsia risk. An untreated mood disorder becomes postpartum depression. An unfilled prescription becomes a readmission.

Europe’s universal systems connect these dots. Pre-pregnancy counseling is embedded in primary care; every pregnant woman receives automatic access to early prenatal visits, nutrition and smoking cessation programs, and postpartum follow-up that lasts at least six months to a year. Home midwife visits after birth are standard in France, the Netherlands, and the Nordic countries, with protocols for checking blood pressure, mental health, lactation, and wound healing. Postpartum cardiomyopathy, suicide, and delayed hemorrhage—major causes of maternal death in the United States—are caught early because coverage is continuous, and visits are proactive. Universal healthcare makes these interventions possible because they are not contingent on employment, income, or billing code. They are simply part of what society funds to protect mothers.

By contrast, U.S. policy treats prenatal care as a temporary insurance episode. Postpartum coverage ends precisely when physiologic stress peaks and when hypertension, cardiomyopathy, and mood disorders emerge. Obstetric teams often lose contact with patients after discharge, not because they lack compassion, but because payment stops. The result is a system that does not support women before pregnancy or after birth—the two times when prevention works best. Universal healthcare would make that continuity standard, not optional, guaranteeing that women are monitored before conception, supported throughout pregnancy, and followed during the critical first postpartum year. In maternal health, that continuity is not a luxury. It is the system itself.

The ethical bottom line

Kahneman reminds us that people are predictably human. Krugman reminds us that markets are predictably unstable without pooling and subsidies. Pregnancy reminds us that timing is everything. If we build coverage that is continuous, simple, and universal, families will come earlier, teams will act sooner, and fewer mothers will die. The U.S. can close the mortality gap with Europe. The fastest route is universal maternity coverage that removes cost at the point of care and guarantees postpartum support for a full year. The data, the psychology, and the economics all point in the same direction.

Notes on sources: CDC 2022 and 2023 U.S. maternal mortality rates, OECD comparison for high-income countries, and French national findings on causes of maternal death are cited above.

I 5000% agree with expanding coverage and benefits/services for pregnant women. But this care must be adequately compensated. OB GYN’s work an incredible number of hours including brutal call shifts. They assume the care and liability for two patients at once. They graduate now with 300k of debit and 10,000’s of hours of training. To suggest that they be compensated at essentially minimum wage is insulting. Not just to the physicians but women. Women and children in the US are undervalued. Care in male dominated fields are compensated at a much higher rate. The additional services so desperately needed for women must be compensated. Not the same low amount, amounting to lowering income to doctors. This will cause practices to close as it can already cost more to see a patient than is compensated. It will cause more hospital labor and deliveries to close. They are already teetering on the edge. ACOG and the AMA have failed to work hard for fair compensation for this field. As a result many OB’s have seen their income decline year after year. This also snowballs into more early retirement from the field, less trainees into the field and no one left to provide the complex care that is desperately needed.