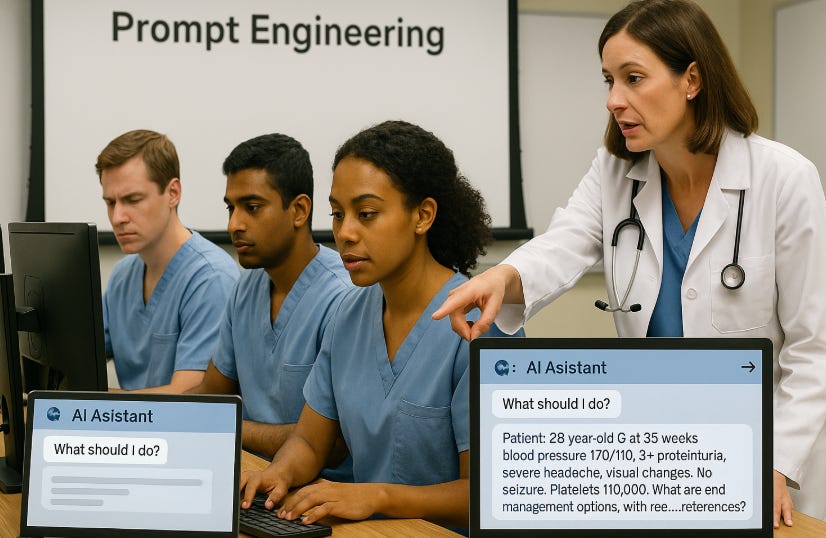

Why Ignoring Prompt Engineering is the Fatal Flaw in AI Education for Doctors

Doctor are not being taught the most important tool of AI

A recent white paper by Elsevier on “empowering residents with AI” sounded thoughtful on the surface: preserve clinical reasoning, supervise carefully, include learners in the discussion. All important points. But the entire document missed the single most important skill that determines whether AI is useful or dangerous: prompt engineering.