When Triage Fails: Why Labor and Delivery Must Treat Every Complaint as Real

Hospitals do not get a second chance to listen. In obstetrics, ignoring a woman in pain is not a clerical error. It is a safety event.

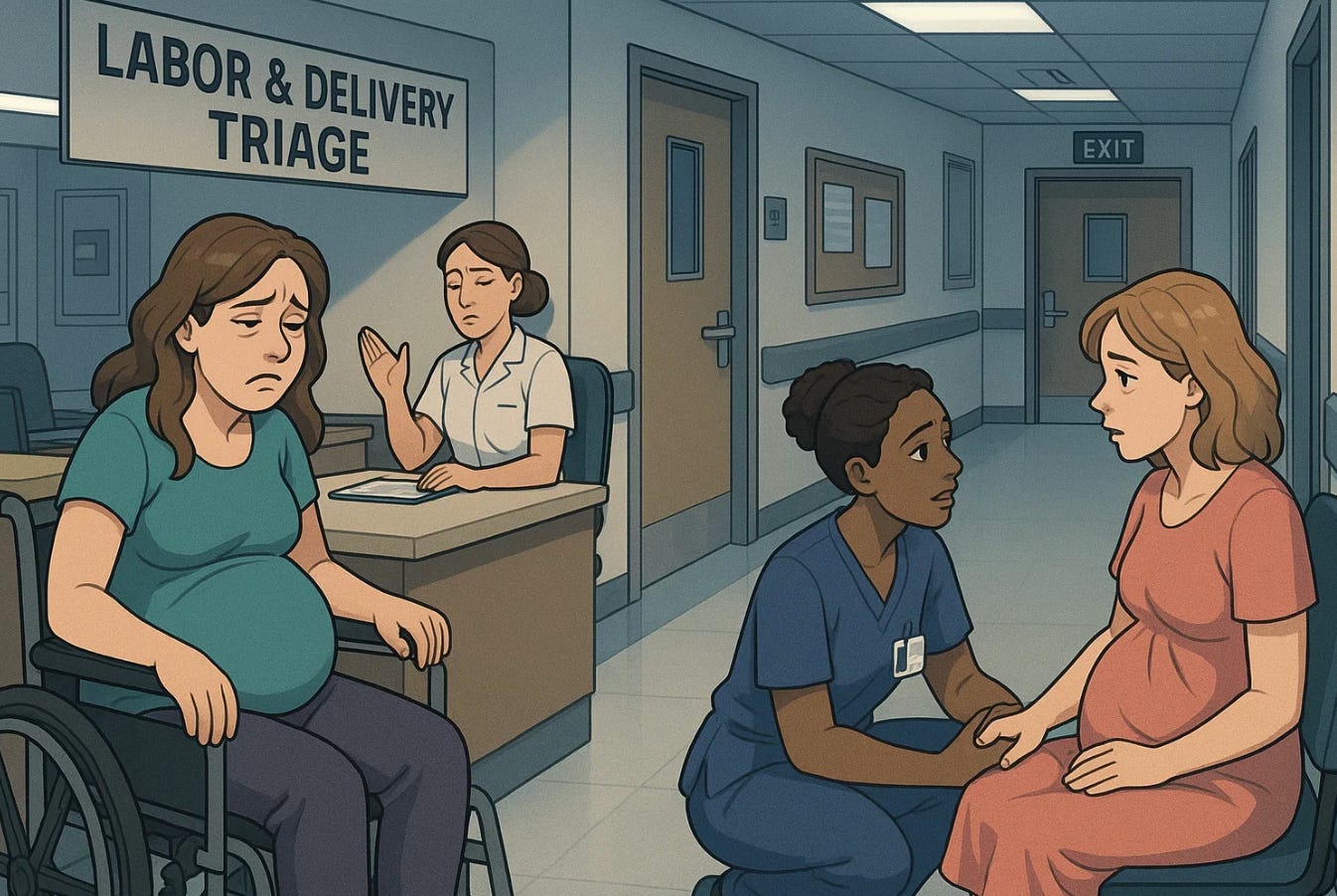

A woman in clear distress arrived at a hospital in Indiana and was told to go home. Eight minutes later she delivered her baby in a car on the side of the road. The video of her breathing in agony, pleading for help, and then being escorted out by security is painful to watch for anyone who works in labor and delivery. The hospital CEO stated bluntly that “compassionate concern is absent when a caregiver fails to listen to a patient who is clearly in pain and vulnerable.” He is right. But in obstetrics, this is not simply about compassion. It is a systems failure with predictable roots.

As an obstetrician who has led a high-volume labor and delivery unit for years, I have seen variations of this scenario more times than I care to admit.

A woman arrives contracting, frightened, and insisting something is happening. She is told she is “not far enough along” or “too early to be admitted.” She is discharged. Minutes later she delivers precipitously at home, in the car, or in the elevator. Every hospital chief of L&D knows these cases. They are not rare. They are a signal that triage is the most underestimated, undertrained, and thinly staffed component of obstetric care.

What Actually Went Wrong

Labor triage is not urgent care. It is the front door to one of the highest-risk environments in medicine. Yet many systems treat triage like a holding zone instead of the critical decision-making node it actually is.

Errors cluster around a few predictable patterns.

First, clinicians underestimate precipitous labor. Progress can go from 3 cm to complete far faster than textbooks suggest, especially in multiparous women. The idea that dilation equals admission is outdated. Pain, behavior, and a woman’s own report of what she feels are powerful diagnostic signals. Ignoring them is not just insensitive. It is clinically dangerous.

Second, hospitals use inconsistent criteria for discharge. Some units rely on a “one exam” rule. Others try to send patients home until they reach arbitrary thresholds. Without clear algorithms, decisions drift toward convenience rather than safety.

Third, empathy erodes under stress. When a unit is overwhelmed, listening is often the first casualty. Staff may default to gatekeeping rather than caregiving. A stern face and a quick dismissal are almost always symptoms of a stressed system, not a single bad clinician.

Why This Keeps Happening

Triage errors flourish in environments without explicit training, standardized protocols, or a culture that regards early labor complaints as legitimate.

In my own department, I learned this the hard way. We saw too many near-miss cases of women sent home who should have stayed. Some delivered in ambulances. Others ruptured membranes in the parking lot. One woman pushed her baby out at home minutes after being discharged because “she was not in active labor.” Her outcome was positive, but only because biology was kind to us that day.

After reviewing case after case, the pattern was obvious. Our staff were not incompetent. They were undertrained for the complexity of triage. They were relying on heuristics. And they lacked a clear, defensible framework for evaluating patients who “did not look ready.”

What Effective Triage Looked Like When We Fixed It

We rebuilt the process with three pillars.

1. Intensive, recurring training for all personnel

Triage is a skill, not a reflex. We instituted regular simulation for residents, nurses, and attendings, including scenarios of:

• precipitous labor

• atypical pain presentations

• misleading early exams

• distressed patients who “don’t look uncomfortable”

• women with prior rapid labors

Simulation changed behavior immediately. Staff became more cautious, more attuned to patient narrative, and far more consistent in decision-making.

2. Clear, written guidelines that eliminate guesswork

Essential: Every L&D unit MUST have clear triage guidelines. If your L&D does not have it, create one immediately

Every pregnant woman presenting with pain, contractions, bleeding, fluid loss, decreased fetal movement, or “something feels wrong” was evaluated by a nurse and physically examined by a physician before discharge. We prohibited decisions based on phone assessments alone. We created criteria for:

• observation periods

• repeat cervical checks

• when to initiate monitoring

• when not to discharge even if dilation is minimal

• mandatory physician exam before leaving the unit

This is exactly the type of change the Indiana hospital is now instituting. It should not take a public failure to adopt it.

3. A culture of empathy backed by accountability

Empathy is not soft. In obstetrics, it is diagnostic. A woman who looks terrified, breathes through pain, or insists “this is different” is giving clinical information. When staff feel supported, trained, and trusted, empathy increases. When they feel rushed or judged for admitting “too many patients,” empathy collapses. We shifted our culture so that listening to patients became a safety practice, not an optional courtesy.

Why This Case Matters for Every Labor Floor

This incident is not an anomaly. It is the predictable result of a system that undervalues the triage moment. The doctor and nurse were fired, but firing individuals rarely fixes the underlying problem.

The solution is structural: training, guidelines, staffing, and culture. Patients should never feel unwelcome when arriving in labor, and no woman should be escorted out while in visible distress.

The Hard Question for All of Us

How many more preventable roadside deliveries, lobby deliveries, or bathroom deliveries are we willing to call “unexpected”? Obstetrics is defined by time-sensitive decisions. When a woman tells us she is in labor, she is usually right. And our obligation is to listen the first time, not after the car delivery.

Reflection / Closing

The core ethical principle in obstetrics is simple: when a pregnant woman seeks care, we err on the side of safety. The Indiana case reminds us that the cost of disregarding a woman’s voice can be immediate and irreversible. The real test of a labor floor is not how it handles emergencies, but how it treats the woman who walks in saying, “Something is wrong.” If we cannot get that moment right, nothing else downstream matters.