When the “Biological Storm” Has a Mechanical Trigger: Amniotic Fluid Embolism (AFE) and Labor Induction

In the wake of a catastrophic maternal collapse from Amniotic Fluid Embolism (AFE), the medical-legal defense often pivots to a single, comforting word: Idiosyncratic.

This long-form analysis reviews the “Anaphylactoid Syndrome” paradigm, tracing the evolution of AFE theory to show how it has been weaponized as a legal defense to obscure the mechanical role of induction.

Late 2025, Hailey Okula, a 33-year-old ER nurse with nearly 500,000 Instagram followers, died two minutes after delivering her first child via C-section. After years of infertility and IVF, she finally held her son Crew for a split second before going into cardiac arrest. The cause: what used to be called amniotic fluid embolism (AFE).

Her husband Matthew, an LA firefighter, told the media he’d never heard of AFE before it killed his wife. “There’s no treatment. There’s no way of diagnosing it,” he said. “It’s just so sad to think that other people have to go through what I’m going through right now.”

The official line is that AFE is unpredictable, unpreventable, and strikes randomly—twice as rare as being struck by lightning. But there’s a problem with that narrative, and it starts with what we’re now being told to call this condition.

We don’t know the circumstances of her death, so what is next is unrelated to her specific cause.

The Name Game: From “Embolism” to “Anaphylactoid Syndrome”

In recent years, there’s been a push to rename amniotic fluid embolism as “Anaphylactoid Syndrome of Pregnancy” (ASP). The rationale sounds scientific: research from the National AFE Registry showed that the condition behaves more like anaphylaxis than a mechanical embolism. Fetal tissue isn’t universally found in affected women. Instead, 66% report prior allergies—double the rate in the general obstetric population—suggesting an immune-mediated catastrophe.

On the surface, this seems like progress. We’re moving from a mechanistic model (fluid blocks vessels) to a more sophisticated immunological understanding (fluid triggers a massive allergic-type reaction).

But here’s what bothers me: renaming the condition “anaphylactoid syndrome” conveniently erases the mechanical trigger that precedes the immune response.

Think about it. An anaphylactoid reaction requires exposure to the triggering substance. A peanut allergy doesn’t manifest unless you eat peanuts. A bee sting allergy doesn’t manifest unless you get stung. And an anaphylactoid reaction to amniotic fluid doesn’t manifest unless amniotic fluid enters the maternal circulation.

The critical question isn’t “why do some women have an anaphylactoid response?” The critical question is: “What caused the breach that allowed amniotic fluid into the maternal bloodstream in the first place?”

By focusing on the immune response and calling it a “syndrome,” we’ve shifted attention away from the antecedent event—the breach itself—and toward an apparently random biological susceptibility. The woman who dies becomes the problem (she was immunologically predisposed), rather than the management that may have created the breach.

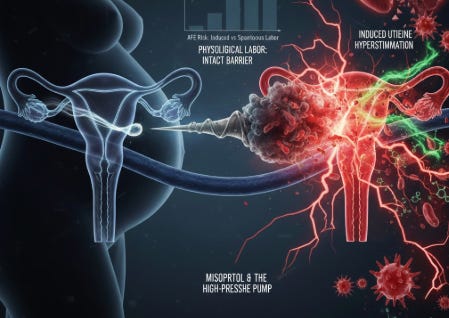

The Breach Doesn’t Happen Spontaneously

Amniotic fluid entering maternal circulation requires disruption of the maternal-fetal barrier. This barrier exists at the placental interface, the cervix, and the uterine wall. Under normal physiological labor, small amounts of fetal material may cross into maternal circulation without incident.

But catastrophic breach—the kind that floods maternal circulation with enough amniotic fluid to trigger cardiovascular collapse—requires significant mechanical disruption. And that disruption has identifiable causes:

Uterine hyperstimulation: When contractions become too frequent or too intense, intrauterine pressure rises dramatically. This pressure gradient can force amniotic fluid across the placental bed or through microscopic tears in the lower uterine segment.

Cervical laceration: Rapid, forceful dilation—whether from precipitous labor or aggressive induction—can tear cervical tissue, creating a direct route for amniotic fluid to enter maternal venous sinuses.

Uterine rupture: The most dramatic breach, where the uterine wall gives way entirely, spilling amniotic fluid directly into the peritoneal cavity and maternal vasculature.

Placental abruption: Premature separation creates a bleeding interface where amniotic fluid can mix with maternal blood.

None of these events are “random.” They have mechanical causes. And many of those causes are iatrogenic—created by our interventions.

What the Population Data Actually Shows

A landmark Canadian study examining over 3 million hospital deliveries found that medical induction of labor was strongly associated with fatal AFE and a near-doubling of overall AFE risk.

The risk factors identified in this and other population-based studies tell a consistent story:

Medical induction of labor

Cesarean delivery

Instrumental vaginal delivery

Cervical laceration or uterine rupture

Polyhydramnios (excess amniotic fluid = more fluid to breach)

Placenta previa or abruption

Eclampsia

Fetal distress (often a marker of difficult labor with strong contractions)

What do these have in common? They’re all associated with increased mechanical stress on the maternal-fetal interface.

The study authors themselves noted: “The increased risks of AFE associated with labour induction and caesarean delivery have implications for elective use of these interventions.”

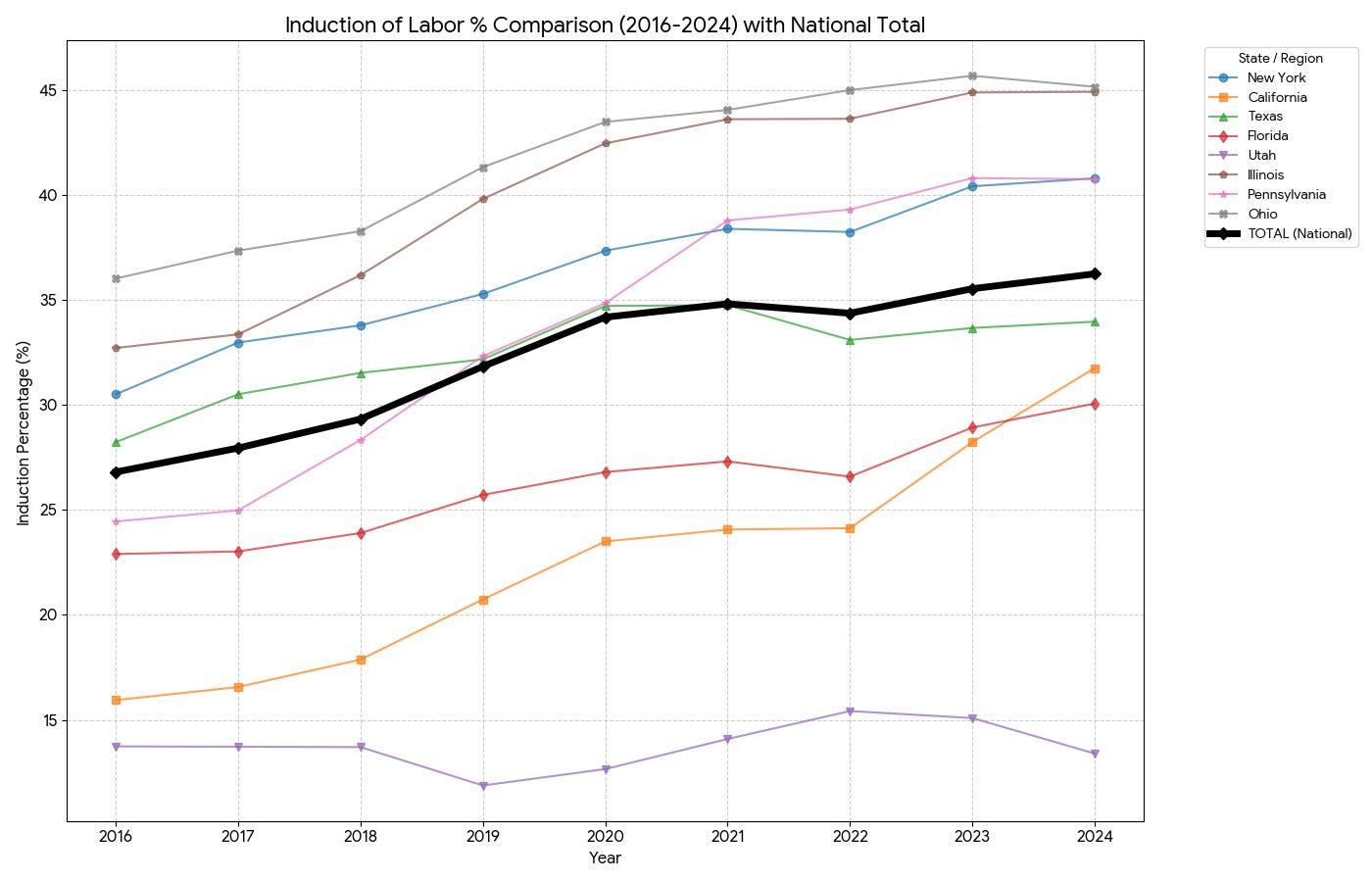

With nearly 4 million births annually and induction rates exceeding 30% in the United States, the MDedge analysis estimated this could translate to 30-40 additional AFE cases and 10-15 deaths per year attributable specifically to induction practices.

We have an induction epidemic in the US:

Data by the CDC WONDER database.

Another experience:

A while back, I raised concerns about misoprostol and its potential link to catastrophic complications including AFE. An experienced ObGyn, someone with decades of practice, attacked me and dismissed my concerns. "There's no evidence," he insisted. “We ar doing so many inductions so it’s not unusual.” Exactly, I thought.

This is the reflexive response whenever anyone questions misoprostol: denial, dismissal, and an appeal to the absence of randomized controlled trials proving causation. But absence of evidence is not evidence of absence—particularly when we're discussing a complication so rare that no RCT could ever be powered to detect it, and when the very terminology we use ("anaphylactoid syndrome") has been engineered to obscure the mechanical antecedents. The resistance to examining misoprostol's role tells you something about how deeply invested the profession is in defending its use.

Misoprostol: The Mechanical Trigger We Don’t Want to Discuss

Among induction agents, misoprostol (Cytotec) deserves particular scrutiny. This prostaglandin analog causes powerful uterine contractions—and unlike oxytocin, which can be titrated and rapidly discontinued, vaginal misoprostol cannot be “turned off” once administered.

The result is a documented pattern of unpredictable uterine hyperstimulation. Tetanic contractions. Precipitous cervical dilation. Exactly the mechanical conditions that would force amniotic fluid across the maternal-fetal barrier.

The FDA has never approved misoprostol for labor induction. The package insert explicitly warns against use in pregnancy. Yet it remains widely used because it’s cheap, shelf-stable, and effective at starting labor.

The question no one wants to ask: How many cases of “anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy” were preceded by misoprostol-induced hyperstimulation that created the breach in the first place?

Our Story

During my tenure overseeing one of the largest Labor and Delivery units in New York—a high-volume center responsible for over 60,000 births—we maintained a strict, intentional policy: we did not use misoprostol for labor induction. Our rationale was rooted in clinical caution regarding the drug’s lack of FDA approval for induction and the potential for unpredictable, catastrophic complications.

Remarkably, throughout those 60,000 deliveries, we did not encounter a single case of amniotic fluid embolism.

While some might dismiss this as statistical coincidence, I firmly believe it was a direct consequence of our refusal to introduce the mechanical volatility associated with misoprostol. By avoiding the “high-pressure pump” of prostaglandin-induced hyperstimulation, we likely preserved the maternal-fetal barrier in cases where more aggressive management might have forced a breach.

Sometimes the best way to manage a “biological storm” is to never provide the mechanical trigger.

Why the Renaming Matters

Language shapes how we think about causation and prevention. Consider the difference:

“Amniotic fluid embolism” implies that fluid entered the circulation (something caused the breach) and blocked vessels (mechanical consequence). The name prompts the question: how did fluid get there?

“Anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy” implies a random immunological event—like any other allergic reaction. The name suggests biological susceptibility rather than iatrogenic causation. It prompts sympathy, not scrutiny.

This isn’t conspiracy. It’s the natural evolution of medical terminology toward language that protects institutions. If AFE is an “anaphylactoid syndrome,” then it’s an unpredictable biological event—tragic but not preventable, and certainly not actionable in court.

But if AFE is the downstream consequence of a mechanical breach that our interventions helped create, then we have to ask uncomfortable questions about induction rates, misoprostol use, and whether the rising tide of managed labor is creating risks we’re not accounting for.

The Two-Hit Hypothesis

Here’s how I conceptualize it: AFE/ASP is a two-hit phenomenon.

Hit 1: The Breach. Something disrupts the maternal-fetal barrier sufficiently to allow significant amniotic fluid into maternal circulation. This is often mechanical—hyperstimulation, laceration, rupture, abruption.

Hit 2: The Response. The maternal immune system reacts to amniotic fluid components with an anaphylactoid cascade—complement activation, cytokine release, cardiovascular collapse, DIC.

The current focus on “anaphylactoid syndrome” addresses only Hit 2. It asks why some women’s immune systems overreact. This is a valid scientific question.

But it completely ignores Hit 1. It doesn’t ask what created the breach. It doesn’t examine whether our labor practices are generating more breaches than necessary. It doesn’t question whether the rising incidence of AFE—which some data suggest has increased as induction rates have risen—reflects an epidemic of immunological susceptibility or an epidemic of iatrogenic trauma.

The Informed Consent Problem

Matthew Okula’s grief-stricken observation haunts me: he’d never heard of AFE before it killed his wife.

How is this possible? How does a woman, a nurse, go through pregnancy, prenatal care, IVF, and delivery without ever being told that a rare but catastrophic complication exists that can kill her within minutes?

The answer is that we don’t routinely discuss AFE in informed consent conversations. We discuss cesarean risks. We discuss epidural risks. We discuss postpartum hemorrhage. But AFE? It’s “too rare to mention.” It would “scare patients unnecessarily.”

Yet if induction doubles the risk of AFE, shouldn’t women considering elective induction know that? If misoprostol carries a particular risk profile, shouldn’t that be part of the conversation?

The renaming to “anaphylactoid syndrome” makes this worse, not better. A syndrome sounds like something that just happens—a random biological event, like a stroke or an aneurysm rupture. It doesn’t sound like something that might be connected to the induction you’re about to receive.

What Would Change If We Took This Seriously?

If we accepted that AFE often has a mechanical trigger—that the breach precedes the reaction—our practice patterns would shift:

More selective induction. If induction carries even a small absolute increase in AFE risk, the calculus for elective induction changes. The convenience of scheduled delivery looks different when weighed against catastrophic complications.

Caution with misoprostol. An agent that cannot be rapidly discontinued, that causes unpredictable hyperstimulation, that has never been FDA-approved for labor induction—perhaps this should be reserved for situations where its benefits clearly outweigh its risks, not used as first-line convenience.

Better monitoring for hyperstimulation. If excessive uterine activity creates breach risk, then recognizing and treating tachysystole becomes a safety priority, not just a labor management issue.

Honest informed consent. Women deserve to know that labor interventions carry risks beyond the ones we routinely discuss. AFE is rare, but it’s real, and its risk may be modifiable based on how we manage labor.

The Bottom Line

Hailey Okula spent her career helping new nurses navigate the healthcare system. She documented her IVF journey, her pregnancy, her hope. She died two minutes after meeting her son.

Was her death a random “anaphylactoid syndrome”—an unpredictable immune event that couldn’t have been prevented?

Or was there a mechanical trigger—something in her labor management that created the breach her immune system then catastrophically responded to?

I don’t know the answer for her specific case. I cannot comment on her care.

But I know this: Our 60,000-delivery experience without misoprostol and without AFE suggests that avoiding unnecessary mechanical triggers may reduce the risk of complications we too readily dismiss as random biology.

I know that population data shows medical induction doubles AFE risk.

I know that renaming the condition “anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy” conveniently shifts focus from the breach to the response—from the iatrogenic trigger to the biological susceptibility.

And I know that a grieving firefighter in Los Angeles had never heard of this condition until it took his wife.

We can do better. We should do better. And the first step is refusing to let comfortable terminology obscure uncomfortable questions about what we’re doing in labor and delivery that might be creating risks that don’t need to exist.

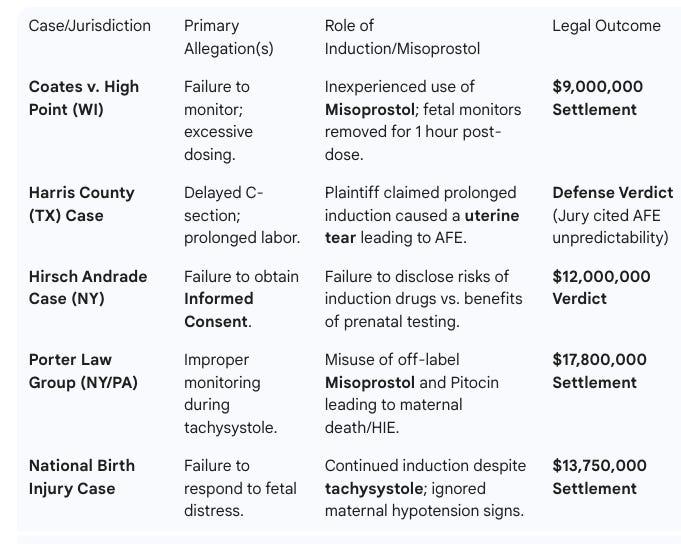

Som Liability Cases associated with Induction/ Misoprostol

References

Clark SL, Hankins GD, Dudley DA, et al. Amniotic fluid embolism: analysis of the national registry. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(4 Pt 1):1158-67.

Kramer MS, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and consequences of amniotic fluid embolism. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013;27(6):546-552. DOI: 10.1111/ppe.12066

Knight M, et al. Amniotic fluid embolism incidence, risk factors and outcomes: a review and recommendations. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:7. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-7

Han Y, Wang S, Xie L. An investigation of the risk factors, an analysis of the cause of death, and the prevention strategies for amniotic fluid embolism. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2020;13(9):6662-6668. DOI: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00001

Kramer MS, Rouleau J, Baskett TF, Joseph KS. Maternal Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. Amniotic-fluid embolism and medical induction of labour: a retrospective, population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2006;368(9545):1444-8. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69607-4

Knight M, Berg C, Brocklehurst P, et al. Amniotic fluid embolism incidence, risk factors and outcomes: a review and recommendations. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:7. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-7

Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM). Amniotic fluid embolism: diagnosis and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(2):B16-24. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.05.012