When Removals Of Warnings Are Political Rather Than Scientific - And ACOG Applauds It

The FDA’s removal of boxed warnings from menopausal hormone therapy, and ACOG’s celebration of it, reveal a troubling disregard for patient autonomy and coherent risk communication.

Definition of the issue: A boxed warning is the strongest safety communication the FDA issues. It exists to alert patients and clinicians to clinically significant risks that require explicit discussion. The FDA recently removed this warning from many menopausal hormone therapy products. The American College of ObGyns (ACOG) and other professional organizations including the Menopause Society and Pharmaceutical companies publicly applauded the move and framed it as the removal of a “barrier” that was supposedly limiting patient access. Lost in this enthusiasm was the fact that the boxed warning was not a barrier. It was a source of information. The celebration itself revealed how easily autonomy becomes collateral damage when clinical messaging is simplified for political or strategic reasons.

Why ACOG’s statement is ethically and clinically flawed

ACOG’s assertion that removing the boxed warning will “increase access” and “remove an unnecessary barrier” misdefines what a boxed warning is. A warning is information, not an obstacle. It does not block prescribing. It does not restrict insurance coverage. It does not prevent clinicians from recommending treatment. Its purpose is to ensure that patients understand clinically meaningful risks before therapy is started. By treating a safety warning as a barrier, ACOG reframes risk communication as if it were paternalistic rather than protective. This is ethically unsound. It privileges throughput over transparency and inadvertently diminishes the informational foundation of shared decision making. ACOG also fails to acknowledge that low-dose vaginal estrogen and systemic estrogen have historically shared a class boxed warning because systemic risk applies to systemic products, not because the FDA was confused about vaginal safety. Instead of welcoming the label change while simultaneously strengthening expectations for clinician counseling, documentation, and informed consent, ACOG portrayed the warning itself as harmful. That inversion of meaning is dangerous. Removing a warning does not create access. It simply removes the most visible cue prompting clinicians to disclose risk. When a professional society cheers that disappearance, it signals that ease of prescribing is being elevated over the patient’s right to a full accounting of benefits, risks, and uncertainties.

Hormone therapy carries real and heterogeneous risks. Thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, stroke, invasive breast cancer, and endometrial cancer for estrogen alone remain clinically relevant. Evidence has evolved, particularly for younger symptomatic women and appropriate timing of initiation, but the need for individualized risk assessment remains unchanged. Revising the boxed warning could have been an opportunity to promote nuanced counseling. Instead it was treated as a symbolic victory. It was presented as liberation from overregulation. In reality it removed the most visible prompt clinicians had to initiate a thorough risk discussion.

ACOG’s framing is central to the ethical problem. ACOG described the boxed warning as a barrier to care. They celebrated its removal as a step toward better access. They did not acknowledge that barriers and warnings are not the same. A warning does not block treatment. It clarifies the stakes of treatment. When an organization positioned as a guardian of women’s health treats high level risk communication as an obstacle rather than a safeguard, it signals a drift away from autonomy toward a narrower advocacy agenda. The result is an unbalanced narrative where access is celebrated and informed consent is an afterthought.

The inconsistency becomes striking when compared with the FDA’s posture on prenatal acetaminophen exposure. The agency has issued cautious public advisories based on observational associations that remain weak and confounded. In that setting the agency amplified a low quality signal. In hormone therapy it erased a high quality one. Patients notice when an agency warns aggressively about Tylenol but removes the strongest warning from estrogen. They notice the inconsistency and it erodes trust. Professional organizations should be the first to challenge that inconsistency. Instead ACOG endorsed it.

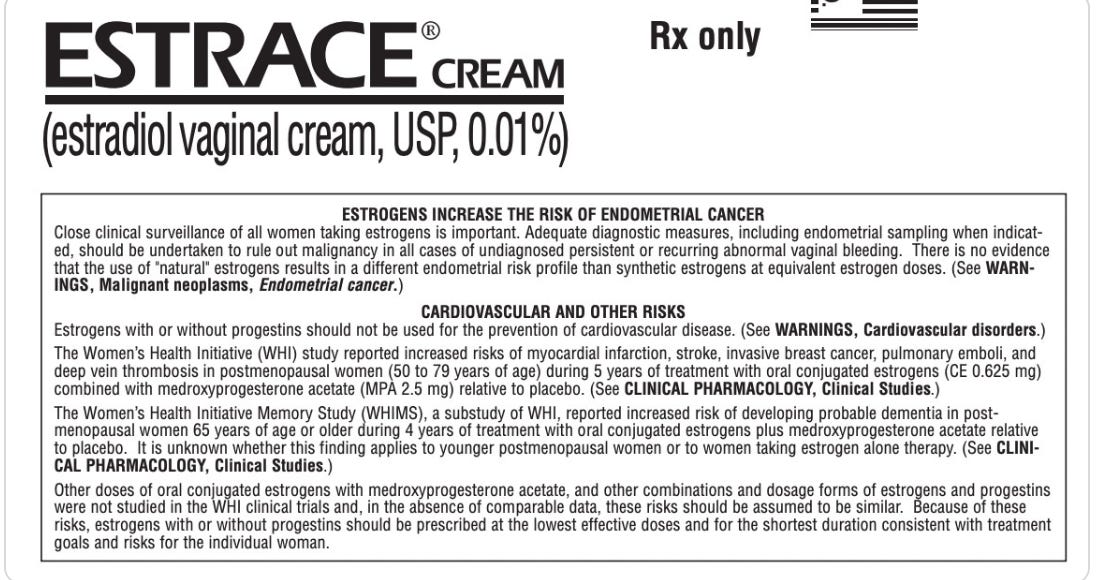

The former boxed warning stated that estrogen-alone and estrogen-plus-progestin regimens were associated with increased risks of endometrial cancer for estrogen alone in women with a uterus, cardiovascular disorders including myocardial infarction, stroke, venous thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism, invasive breast cancer, and probable dementia in older postmenopausal women. It emphasized that hormone therapy should not be used for the prevention of cardiovascular disease or dementia, that the lowest effective dose should be used for the shortest duration consistent with treatment goals and risks, and that any recurrent genital bleeding required evaluation to exclude malignancy.

Legally permissible verbatim excerpts from FDA-approved labels

“WARNING: ENDOMETRIAL CANCER, CARDIOVASCULAR DISORDERS, BREAST CANCER and PROBABLE DEMENTIA. See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning.”

“Estrogen plus progestin therapy should not be used for the prevention of cardiovascular disease or dementia.”

The ethical issue is not whether the warning needed revision. It is the disappearance of the warning without adequate reinforcement of counseling responsibilities. The FDA removed a visible signal. ACOG applauded the removal. No one emphasized that the burden of risk communication now rests entirely on clinicians who already have limited time, limited support, and increasing clinical complexity.

Autonomy is not strengthened when risk becomes harder for patients to see. It is strengthened when risk is named clearly and discussed transparently. Removing a warning without replacing it with structured counseling tools, decision aids, or improved documentation practices does not increase access. It merely shifts responsibility to the clinician while reducing the patient’s opportunity to understand the full landscape of benefits and risks.

Closing reflection: When professional societies celebrate the disappearance of critical safety information as the removal of a barrier, autonomy is the casualty. If the FDA will not protect coherent risk communication, the profession must. Silence is not neutrality. It is complicity.