Unequal Care: When Neutral Policies Produce Unequal Care

Health disparities are not always caused by prejudice. Sometimes they are built into the payment system.

We often talk about inequity in medicine as if it requires a bad actor. A biased physician. A discriminatory policy. An explicit refusal of care. But modern health systems rarely work that way.

Unequal access to care more often arises from neutral rules that predictably affect different populations in different ways. This is the difference between intentional discrimination and structural inequity.

Structural inequity means a policy treats everyone the same on paper, yet the outcome is unequal. No one intends to exclude patients. No one needs to say we don’t treat you. The system quietly does it instead.

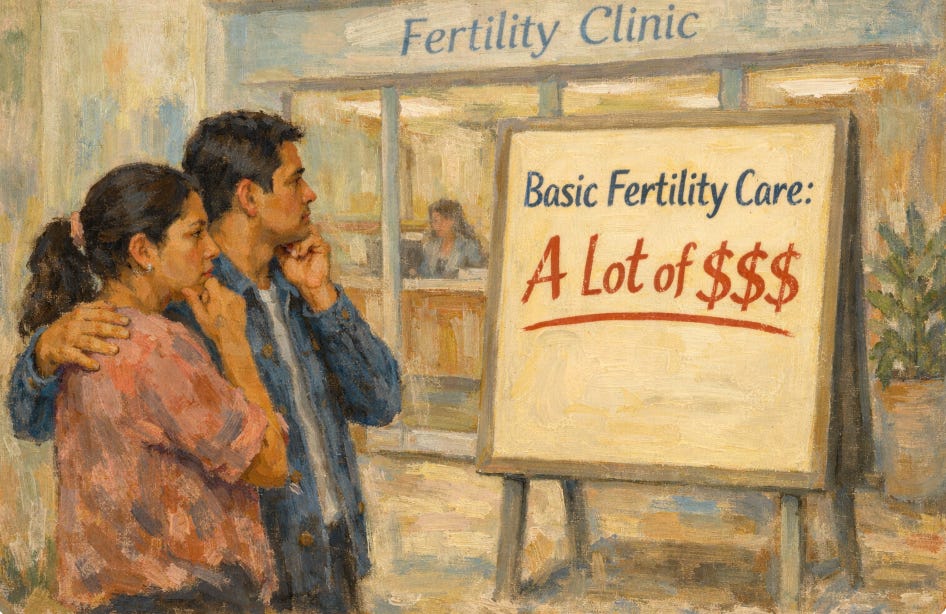

Consider payment models in American health care. Many specialized services operate largely outside traditional insurance networks. Some practices accept only certain commercial plans. Others are effectively self-pay. These decisions are usually explained as operational necessity. Reimbursement is low. Administrative burden is high. Staffing is expensive.

Each individual decision is rational at the level of the practice.

But patient populations are not evenly distributed across insurance types.

Medicaid covers a very large share of births in the United States and disproportionately insures lower-income patients and many minority communities. When a service is inaccessible to Medicaid patients, the policy is not explicitly racial. Yet the effect is predictable. Entire groups encounter barriers before they ever reach a waiting room.

This is not only about fertility treatment. It appears in maternal-fetal medicine referral networks, subspecialty gynecology, postpartum mental health care, and even basic prenatal services in certain regions. The exclusion rarely looks dramatic. It looks administrative. Insurance not accepted. Out-of-network only. Up-front payment required. Limited appointment availability.

No single physician may be acting unfairly. The inequity emerges from aggregated rational behavior.

When Investment Replaces Mission

Private investment in medicine complicates this further. According to a JAMA study, investor-owned systems now perform the majority of IVF procedures in the United States. These systems are designed to improve efficiency, scale operations, and maintain financial sustainability. None of these goals are inherently unethical. Hospitals and practices must remain financially viable to exist at all.

Yet financial optimization and equitable access are not the same objective. When revenue stability becomes the primary operational constraint, patient selection pressure appears even if no one intends it.

Fertility medicine has characteristics that are unusually attractive to investors. Much of the care is self-pay. Treatments often occur in repeated cycles. Clinics can add revenue through laboratory services, genetic testing, and storage. Because pricing is less constrained by insurers than in most medical fields, financial performance depends more on market demand than reimbursement policy. That makes the specialty easier to scale and sell as a business platform.

Typical U.S. reproductive endocrinology and infertility physicians earn roughly $300,000 to $450,000 annually, with many earning considerably more. Some high-volume fertility doctors and program directors have been reported to earn multi-million-dollar annual compensation.

System Ethics, Not Just Bedside Ethics

Clinicians still make clinical decisions, but they do not usually control who reaches them. Access decisions increasingly occur upstream: scheduling policies, insurance contracts, pricing structures. The ethical challenge shifts. It is no longer only bedside ethics. It is system ethics.

Physicians traditionally view professionalism as what happens in the exam room. In reality, professionalism now includes attention to the architecture surrounding the exam room. If entire patient populations predictably cannot enter the system, the fairness of the care inside the system is no longer the central question.

This does not mean every practice can accept every insurance plan. Financial constraints are real. Staffing shortages are real. Administrative complexity is real. But acknowledging reality does not eliminate ethical responsibility. It clarifies it.

The key issue is not whether discrimination is intended. It is whether exclusion is foreseeable.

When neutral policies consistently produce unequal access, the ethical question becomes unavoidable. A health system cannot evaluate itself only by the quality of care it provides to those it sees. It must also consider who it never sees at all.

The Next Ethical Frontier

The future debate about equity in medicine will move away from accusations of individual bias and toward examination of system design. Payment structures, referral networks, and ownership models increasingly determine access to care more than individual physician attitudes.

Structural inequity is uncomfortable because no single person causes it. But that is precisely why it persists. Problems without identifiable villains are harder to fix.

Medicine has spent decades improving treatments. The next ethical frontier is improving entry into treatment.