When Lower Cesarean Rates Become a Story Instead of a Safety Question

A falling cesarean rate means nothing unless mothers and babies are safer.

A cesarean delivery is a surgical birth used when it can protect the health of a mother, a baby, or both. It is one of the most important lifesaving procedures in obstetrics. The purpose of a cesarean is simple. It is meant to improve outcomes. It is successful when used for the right reasons and at the right time. That is why any claim that fewer cesareans are automatically better needs careful scrutiny.

Every once in a while, a story is published celebrating a hospital that “cut its cesarean rate.” It sounds like progress. It makes headlines. It gives the impression of success. But it also leaves out the only question that matters. Did mothers and babies actually do better.

A lower cesarean rate can be meaningful only when paired with better outcomes. On its own, the rate is not a measure of quality. It is a utilization statistic.

That is the core issue when journalists cheer declining cesarean numbers without presenting data that mothers and newborns were safer as a result. Without outcomes, the public receives a narrative that is not just incomplete. It is misleading.

The New York Times story is a strong example. It frames cesareans as the main threat in maternity care. It repeats familiar talking points about overuse, physician preferences, reimbursement, and culture.

But it does not report whether the hospital that lowered its cesarean rate saw changes in outcomes such as uterine rupture, shoulder dystocia injury, cord acidemia, NICU admissions, postpartum hemorrhage, maternal ICU transfers, or even maternal or neonatal deaths. These are not exotic metrics. Every hospital tracks them. Leaving them out distorts the story and encourages policy recommendations without evidence.

Real safety cannot be inferred from fewer operations. It must be demonstrated with data. A shift from a 40 percent cesarean rate to 25 percent means nothing unless both mothers and babies experienced fewer complications. Without that verification, the story becomes celebration of an administrative statistic instead of an evaluation of care.

There is a second problem. The article implies that midwifery routing, labor positioning techniques, and peer comparison boards are proven interventions. No evidence is presented.

No acknowledgment is made that many hospitals with lower cesarean rates report higher rates of birth trauma or neonatal morbidity.

The article also overlooks the fact that healthy first time mothers are not one uniform group. Maternal age continues to rise. Obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and IVF pregnancies are more common. These clinical realities affect outcomes far more than workflow redesign.

The ethical issue is clear. When journalists celebrate lower cesarean rates without reporting harm surveillance, they risk putting pressure on clinicians. That pressure encourages avoidance of surgery even when a cesarean is indicated. Professional bodies in multiple countries have warned about this dynamic. It places physicians in a conflicted position, balancing medical judgment against institutional targets and public expectations. Pregnant women can also be misled. Many will walk away believing that avoiding a cesarean is inherently safer. In reality, the safest outcome is a healthy mother and a neurologically intact baby. The mode of delivery is a means to that end, not the end itself.

International experience shows what can happen when systems push too hard to reduce cesareans. Several countries reversed national low-cesarean policies after increases in adverse perinatal events. Yet this context is absent from the reporting.

A responsible story would present both sides. It would include operative morbidity, infection, transfusion rates, thromboembolic events, NICU admissions, five minute Apgar scores, cord pH data, shoulder dystocia injuries, and perinatal mortality. It would compare these before and after cesarean reduction. It would stratify by parity, age, BMI, race and ethnicity, and insurance status. It would ask whether vulnerable groups were harmed. It would also ask whether informed consent was consistently honored and whether women who wanted cesareans were denied them.

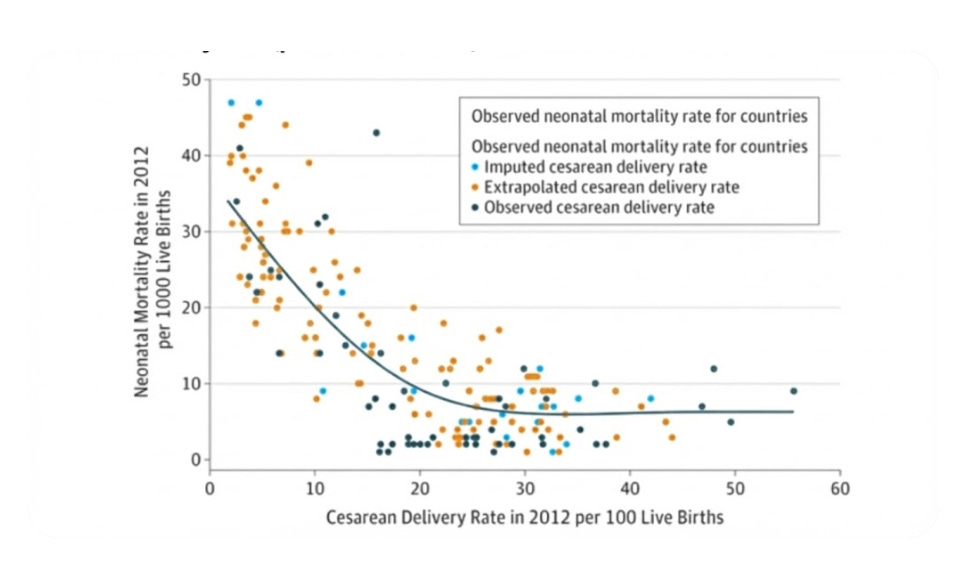

This graph above is from a JAMA study showing that optimal neonatal mortality is reached around a 30% cesarean delivery rate. The rate we presently see in the US.

The issue also intersects with what we know about artificial intelligence in clinical communication. Studies confirm that incomplete or inaccurate language in medical communications carries real risks. For example, recent investigations into AI translation show clinically significant errors in multiple languages when instructions are not rigorously validated. These errors include omissions and mistranslations that could affect patient care. The lesson is simple. Accuracy and full context matter. Missing information can harm. In obstetrics, the stakes are even higher because two patients are involved and outcomes can change in minutes.

Hospitals that redesign their systems to reduce cesarean use must also commit to transparent reporting of adverse events. Journalists covering these changes must insist on seeing those data. Without them, we are not reporting. We are advocating. When the subject is maternal and neonatal safety, that is not acceptable.

Obstetrics is the only specialty that cares for two patients at once. It is also the one specialty where seconds, not minutes, determine outcomes. Avoiding a necessary cesarean can cause catastrophic injury. Delaying an indicated operation can change the course of a child’s life. These realities must be part of any discussion of cesarean reduction. They cannot be edited out to fit a narrative of success.

For a cesarean reduction effort to be called a success, both mother and baby must be demonstrably safer. Only outcome data can answer that. Without those data, celebration is premature and unprofessional.

Pregnant women deserve better information. Clinicians deserve fair representation of the tradeoffs they face every day. The public deserves coverage that honors the seriousness of maternity care.

Reflection:

Safety cannot be inferred from ideology. It must be measured. Journalism that omits outcomes undermines informed decision making and erodes trust in maternity care reporting.