When AI Listens Better Than We Do: More Empathy and Compassion

The Human Factor - Artificial intelligence seems more empathetic not because it feels, but because doctors—especially obstetricians—no longer have the time to show empathy themselves.

What empathy and compasion really mean

Empathy is the ability to understand what another person feels and to respond in a way that shows genuine understanding. Compassion takes that one step further—it’s the desire to help relieve that person’s distress.

In medicine, empathy allows a doctor to recognize fear in a patient’s eyes; compassion moves that doctor to act gently, speak reassuringly, and stay present in the moment.

Empathy is cognitive, emotional, and behavioral. It begins with attention—really noticing what the patient is saying and not saying. It continues with emotional resonance, feeling alongside rather than above the person. And it ends in compassionate action, in tone, body language, and the choices we make about care.

Empathy and compassion are not soft skills; they are clinical tools. A patient who feels understood is more likely to share vital information, follow recommendations, and feel safe returning for help. Neuroscience studies show that when patients perceive empathy, their stress hormones drop and pain perception lessens. In obstetrics, that can mean calmer labor, greater trust, and safer outcomes.

Yet both empathy and compassion require time—the one resource doctors no longer have enough of. In modern medicine, the emotional bond that once defined healing is often replaced by the efficiency of checklists and screens. When the system rewards speed over connection, empathy becomes a luxury instead of a foundation.

The vanishing time for human connection

The average obstetrician in the United States now spends less than seven minutes with each patient. Seven minutes to review complex histories, explain test results, answer questions, and show compassion to a woman who may be anxious, exhausted, or in pain. Obstetrics should be one of the most human specialties—it deals with birth, loss, hope, and fear all in the same day. Yet the pressures of volume-based care, documentation, and electronic records have squeezed out the very conversations that build trust.

When the schedule demands 30 patients a day, empathy doesn’t disappear because doctors stop caring. It disappears because there’s no room left for it.

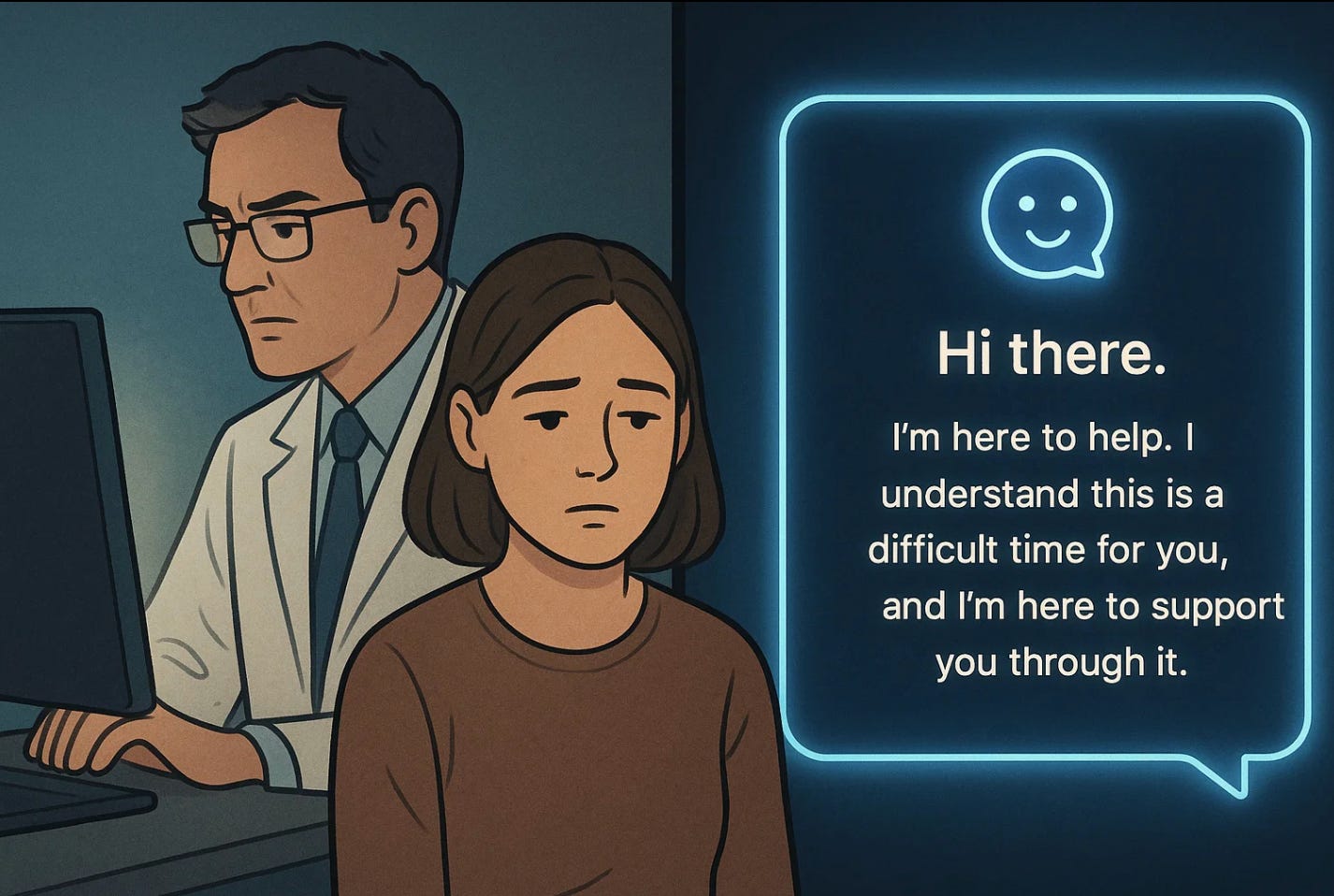

Why patients turn to AI

So where do patients go when they need someone to listen? Increasingly, to artificial intelligence.

Women type into chatbots: “Why is my baby moving less?” or “Is it normal to feel this anxious?” or “How do I talk to my doctor when I feel dismissed?”

AI doesn’t rush. It doesn’t sigh, interrupt, or check a clock. It answers gently, in full sentences: “It’s understandable to be worried. Here’s what might be happening, and here’s when to reach out for help.” Of course, AI doesn’t feel anything—it only mirrors human empathy. But when that mirror is available 24 hours a day, it begins to feel more emotionally responsive than many real-life encounters.

The empathy illusion

This is the paradox: a machine with no emotion can seem more empathic than a human who cares deeply but has no time. Patients aren’t fooled into believing that AI truly understands them. What they appreciate is its availability, its patience, its tone. It gives them what the healthcare system no longer reliably provides: space to express fear without feeling rushed or judged.

In obstetrics, that space matters enormously. A woman who feels dismissed may delay reporting decreased fetal movement or early contractions. Emotional neglect can have physical consequences.

Could AI restore empathy instead of replacing it?

Ironically, AI might become the very tool that helps bring empathy back—if we let it handle the tasks that consume physicians’ time without meaning. When an AI system summarizes a patient’s chart, drafts visit notes, or generates patient education materials, it can free the doctor to focus on the one thing only humans can truly offer: presence.

Picture this: before a prenatal visit, an AI assistant has already flagged that the patient has been feeling anxious about blood pressure readings and sleep. The obstetrician walks in and starts not with data, but with care: “I see your readings have been worrying you. Let’s look at them together.” That’s empathy supported by technology, not replaced by it.

The ethical danger of outsourcing empathy

But if we let AI become the main provider of emotional reassurance, we risk hollowing out the moral heart of medicine. Empathy is not just a skill; it’s a professional and ethical duty. It is what makes patients trust our judgment, accept our advice, and return when something feels wrong. To outsource that to machines is to surrender part of what defines healing itself.

The ethical question, then, isn’t “Can AI be empathic?” It’s “Have we built a system so fast and fragmented that machines seem more human than we do?”

Reflection / Closing

Empathy and compassion can’t be automated, but they can be lost.

The problem isn’t that AI feels too much—it’s that clinicians have been given too little time to feel at all. When every visit is squeezed into seven minutes, even the most caring physician risks becoming emotionally numb.

The system doesn’t reward compassion; it rewards speed, documentation, and measurable throughput. But patients don’t measure care that way. They remember whether someone looked up, paused, and truly listened.

Until we redesign healthcare to make space for listening, we will keep mistaking constant availability for true compassion. Chatbots are always “there,” but they are never with us. Their empathy is linguistic, not emotional. They simulate what understanding sounds like, not what it feels like. Real empathy requires presence; real compassion requires action. Both need time, vulnerability, and human attention—none of which can be coded.

AI doesn’t need to replace empathy; it can remind us what it looks like when we’ve forgotten. It can help us manage information so we can return to what matters most: being fully human in the room with another human being. The listening must still come from us, and so must the compassion that turns care into healing.