When Agreement Between Colleagues Becomes Evasion

Why acknowledging risk without acting on it is not ethical neutrality

A colleague recently replied to one of our posts on home birth with a familiar refrain. We agree home births are more dangerous than hospital births. We just disagree on what to do with that knowledge. It was framed as collegial. It was also, in its own way, revealing.

Let me just pivot a little. How would you respond to a colleague telling you: “We agree smoking is more dangerous than not smoking. We just disagree on what to do with that knowledge.” I would tell a pregnant woman to stop smoking. Is there anything else? Tell her smoking is OK? Tell her the risks but tell her I have no opinion whether she should continue to smoke?

He would tell her: "I will inform you of the increased perinatal mortality risk, but I decline to make a professional recommendation about whether you should accept that risk." That's not autonomy-respecting informed consent. That's information dumping followed by moral abdication.

What this is about

This essay is about a recurring ethical move in obstetrics. Risk is acknowledged. Data are accepted. Harm is conceded. And then responsibility quietly stops. The argument shifts from evidence to metaphor, from outcomes to dystopia, from newborns to novels.

The colleague’s position, summarized fairly

The response makes several claims.

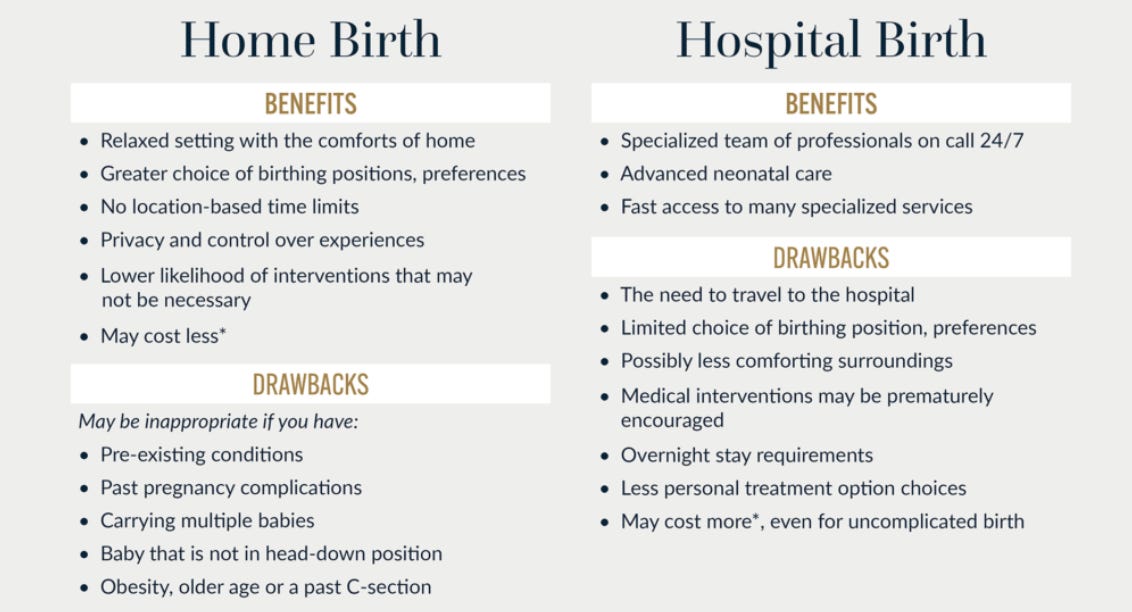

First, that we already agree on the facts. Planned home birth carries higher perinatal risk than hospital birth.

Second, that continuing to present data is redundant because the disagreement is not about evidence but about action.

Third, that the appropriate response is disclosure, not restriction. Inform women of excess risk.

Make home birth safer. Make hospitals more attractive. Do not legislate or criminalize. Finally, it warns that any attempt to limit risk-taking in pregnancy leads us down a slippery slope toward a surveillance state, invoking The Handmaid’s Tale and images of women needing passports to eat fast food or turn left in traffic.

On the surface, this sounds like a defense of autonomy. In reality, it is something else.

Where the argument fails

The first problem is categorical confusion. No serious clinician is arguing that pregnant women should be stripped of rights, criminalized, or placed under state control. That is a strawman. The real question is whether clinicians and professional societies have ethical obligations beyond disclosure when a choice predictably increases preventable harm to a third party, the fetus and future child.

Obstetrics is not unique in this regard. We already accept limits on “informed choice” in medicine. We do not offer unsafe anesthesia options simply because a patient understands the risk. We do not provide substandard chemotherapy because a patient prefers it. We do not allow surgeons to operate in environments that lack basic safety infrastructure. These are not dystopian controls. They are professional standards.

The second problem is the misuse of autonomy language. In clinical ethics, autonomy does not obligate clinicians to validate every informed preference. It obligates us to respect persons while exercising professional judgment.

Advising against a high-risk setting and declining to support it is not coercion. It is integrity. The inverse is also true. Failing to advise against a setting known to carry excess, preventable risk is professionally negligent, not ethically neutral. When clinicians remain silent, equivocal, or “agnostic” in the face of foreseeable harm, they are not respecting autonomy. They are abandoning their duty to warn, to guide, and to protect. The third problem is the slippery slope argument itself. Comparing limits on planned home birth to banning cheeseburgers or left turns is rhetorically clever and ethically unserious. Pregnancy is not analogous to daily lifestyle risks because pregnancy creates a time-limited, predictable, and preventable window of vulnerability for another human being. That distinction matters. Ethics depends on distinctions. If you have a pregnant patient who smokes or takes drugs, your professional obligation is to strongly recommend against it.

What is actually being avoided

The line “we agree on the risk but disagree on what to do with it” sounds reasonable. But it functions as an ethical off-ramp. Once risk is acknowledged yet neutralized by autonomy rhetoric, no further responsibility is required. No thresholds need to be defined. No accountability is owed when harm occurs. The clinician becomes a bystander armed with a consent form.

This is not ethical humility. It is ethical minimalism.

A preventive ethics lens

Obstetrics has always been a preventive discipline. We act before catastrophe, not after. We induce labor to prevent stillbirth. We recommend cesarean delivery to prevent uterine rupture. We restrict trial of labor when conditions exceed acceptable risk. None of this is dystopian. It is the core of professional responsibility.

From a preventive ethics standpoint, the question is not “Can a woman choose risk?” Of course she can. The question is “What risks should clinicians and systems actively normalize, support, or facilitate?” Planned home birth crosses that line when safer alternatives exist and when excess risk is borne primarily by the fetus and newborn.

Where this leaves us

I appreciate the colleague’s acknowledgment of risk and the collegial tone at the end. But passion is not the issue. Responsibility is. We cannot keep pretending that presenting data exhausts our ethical duty. At some point, agreement on harm demands more than a shrug and a metaphor.

The real ethical discomfort is not about dystopia. It is about saying no. And in medicine, especially in obstetrics, saying no to prevent harm is sometimes the most ethical act we have.

Why home birth is not ethically unique

One move that often derails this discussion is the claim that pregnancy is categorically different from every other domain of professional risk. It is not. What makes planned home birth ethically relevant is not that it involves pregnancy. It is that it involves unqualified or insufficiently regulated practitioners operating outside enforceable safety standards, with foreseeable adverse outcomes.

Every other profession already draws this line.

If an unlicensed contractor repeatedly causes structural failures, we do not respond by saying homeowners were informed of the risk and therefore nothing more can be done. The contractor is stopped.

If an unqualified aviation mechanic ignores maintenance standards and planes crash, we do not defend that as consumer choice. The mechanic loses certification. If an uncertified daycare provider repeatedly harms children, the response is not better brochures. The response is removal from practice.

Home birth is not different.

When a home birth midwife refuses to establish or follow evidence-based guidelines, declines meaningful peer review, resists outcome reporting, and continues to practice despite recurrent neonatal injury or death, the ethical problem is no longer maternal autonomy. It is professional negligence operating without accountability.

At that point, inaction becomes complicity.

The claim that “we should just inform women of the risk” collapses under comparison with every other safety-critical field. In no other profession do we tolerate repeated preventable harm simply because the client signed a consent form. In no other domain do we allow practitioners to opt out of standards while continuing to expose third parties to serious risk.

The fetus and newborn cannot consent. They cannot shop for safer providers. They rely entirely on the professional integrity of the adults involved.

What is our responsibility

Our responsibility as physicians, ethicists, and professional leaders is not to police women. It is to draw firm boundaries around professional conduct. That includes insisting on minimum training standards, transparent outcome reporting, enforceable transfer protocols, close relationships with a hospital, and consequences when harm predictably recurs.

If a practice setting cannot meet basic safety thresholds and refuses regulation, the ethical response is not neutrality. It is intervention.

This is not dystopia. It is how every safety-oriented profession already functions.

The uncomfortable truth is this: once we accept that some practices predictably cause avoidable harm, continuing to tolerate them under the banner of autonomy is not respect. It is abdication.

And abdication is not an ethical position.

Reflection

If we truly believe that some practices predictably cause avoidable harm, what does professionalism require of us when autonomy and prevention collide? That is the question worth debating, without novels, without hyperbole, and without pretending that inaction is neutrality.

The smoking comparison really cuts through the muddiness here. Once risk is acknowledged but action gets deferred to "autonomy," it does feel like an off-ramp rather than an ethical stance. The distinction between preventable harm with third-party consequences versus personal lifestyle choices is critical. I've seen this play out in consultng work where acknowledging a problem but refusing to act on it becomes itsown form of negligence. The slippery slope argument is rhetorically strong but structurally weak when compared to how every other safety profession operates.

The reasoning to engage professionals in any field is to avail yourself of the greater knowledge and expertise that they possess. After considering and presenting the options I believe there is an ethical imperative to recommend the solution which is most likely to yield the best/most optimal/ desired outcome. We are the most highly trained, experienced and knowledgeable professionals who have dedicated our lives to providing safe, protected and productive childbirth to women and their unborn/ newborn children. We can’t abandon this responsibility regardless of misguided populist rhetoric.