Virginia Apgar and the First Minutes of Life

How a simple score reshaped accountability and still challenges obstetrics to confront what it overlooks.

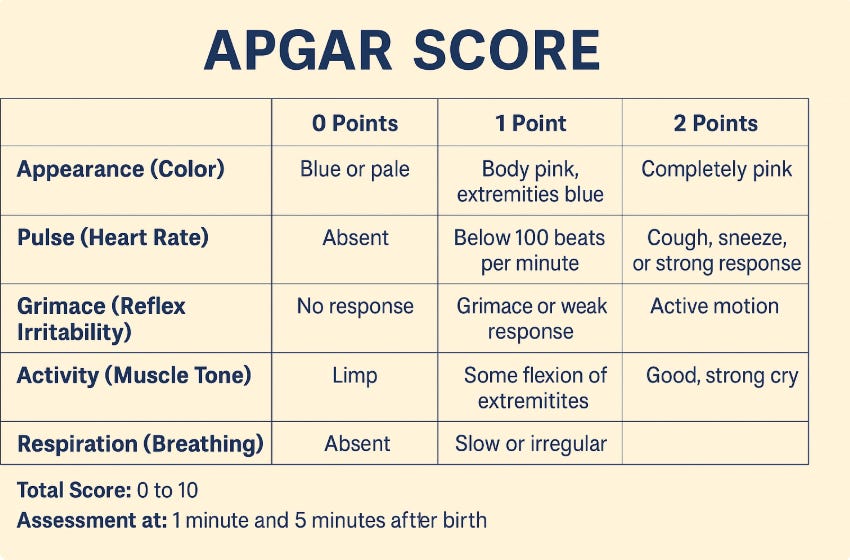

Virginia Apgar (1909–1974) was an American anesthesiologist whose work transformed the evaluation of newborns and reshaped expectations for obstetric accountability. Trained at Columbia-Presbyterian and later a leader in perinatal public health at the March of Dimes, she introduced the Apgar Score in 1953 as a standardized system for assessing newborn condition at one and five minutes of life. Her contribution was not only scientific but ethical. She created a language that forced clinicians to look directly at the newborn and to respond quickly when distress appeared. Apgar believed that measurement saves lives, that clarity drives improvement, and that newborns deserved more than assumptions. Her discipline and imagination continue to guide obstetric thinking today.

1. Seeing What Had Been Invisible

Before Apgar’s work, newborn condition was often described vaguely as “good,” “poor,” or “asphyxiated.” These terms reflected subjective impressions rather than actionable information. Apgar recognized that such ambiguity harmed both babies and clinicians. She created a tool that brought newborn physiology into focus. By assigning numeric values to appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration, she transformed a clinical moment previously governed by instinct into one governed by clarity. This change was profound because it forced hospitals to integrate newborn well-being into the evaluation of obstetric care. What had been invisible was now visible, measurable, and impossible to ignore

2. Simplicity With Consequence

The Apgar Score succeeded because it demanded almost nothing in resources yet changed everything in practice. Its simplicity was not a compromise. It was a strategy. Apgar understood that clinicians under pressure need tools that are fast, intuitive, and reproducible. By offering a ten-point system that could be completed in seconds, she ensured universal adoption. The score revealed patterns of maternal anesthesia complications, differences in neonatal outcomes by delivery technique, and gaps in resuscitation training. Simplicity became a vehicle for accountability. A low score was a call to action, not a judgment. It created a shared responsibility among obstetricians, anesthesiologists, pediatricians, and nurses.

3. A New Standard for Teamwork

Apgar worked across disciplines long before collaborative perinatal teams became standard. She understood that a safe birth required coordinated timing, clear communication, and aligned priorities. The Apgar Score became a shared language that united clinicians who often operated in parallel but not in partnership. Birth rooms became more synchronized, because everyone understood what a score of three or eight meant and what needed to happen next. Her score helped break down silos by creating a shared framework for urgency. The ethos of teamwork that defines today’s obstetric and neonatal units owes much to the structure she introduced.

4. The Score as a Mirror of the System

Apgar knew that newborn outcomes did not simply reflect the baby’s physiology. They reflected the quality of care. The score became a mirror that exposed variations by time of day, training level, resource availability, and adherence to protocols. This transparency was uncomfortable for some, but she insisted that discomfort is part of progress. Modern obstetrics still grapples with similar issues. Variation in fetal monitoring interpretation, inconsistent emergency response, and wide differences in maternal morbidity remain common. Apgar’s work suggests that without simple, reliable measures, these patterns remain hidden. Her legacy challenges us to create new metrics that illuminate maternal safety with the same clarity her score brought to newborns.

5. The Maternal Parallel We Still Lack

Despite decades of progress, obstetrics has not created a universally accepted maternal equivalent of the Apgar Score. Hemorrhage risk, hypertensive crises, sepsis indicators, and triage delays lack the standardized scoring system that newborn assessment enjoys. This absence carries consequences. Without consistent measurement, hospitals struggle to identify early warning signs or benchmark performance. Apgar’s philosophy implies that the same urgency applied to newborn care should apply to maternal well-being. A structured maternal score would not replace clinical judgment. It would sharpen it. It would ensure that the mother is not overshadowed by the moment of birth that she makes possible.

6. Precision as an Ethical Act

Apgar’s scientific rigor was inseparable from her ethical commitments. She believed that if clinicians can know more, they must. If systems can improve, they should. The Apgar Score exemplifies this mindset. Precision protects the vulnerable. Clarity reduces error. Structured observation prevents excuses. These principles remain critical in an era of rising maternal morbidity, staffing shortages, and system strain. Apgar reminds us that ethical care begins with knowing exactly what is happening and responding promptly. Her commitment to precision challenges clinicians not only to observe but to act.

7. The Legacy of Expecting Better

Virginia Apgar changed expectations. She demonstrated that even a deeply traditional field like obstetrics could evolve rapidly when given the right tool. Her score still appears on whiteboards and bedside charts around the world, a quiet reminder that improvement begins with attention. She taught clinicians to expect better from themselves and from their systems. Her legacy is not just a scoring system. It is a philosophy of responsibility. Birth is unpredictable, but care should never be casual. In every delivery room, the Apgar Score represents a promise that the newborn will be seen clearly and cared for promptly.

Reflection

Apgar’s achievement was simple and radical. She measured what others ignored and forced a profession to confront its blind spots. Today, obstetrics faces new blind spots, many affecting maternal safety rather than neonatal condition. The question her life poses is direct. What are we failing to measure now that future generations will see as obvious. Until we answer that question with the same clarity she brought to the first minutes of life, her work remains unfinished.

Please contact me at jmissanelligrob@aol.com.

Virginia Apgar was complicit with her Yale collegue Edward Hon, the Inventor of the Electronic Fetal Monitor, in extablishing one of the greatest bamboozals in medical history. She gave her score to the newborn babies at Yale and if the score was 6 or less, she looked at the graph of what Hon had produced during the labor of those newborns, saw that there were decelerations in the fetal heart, confirmed that there must have been hypoxia as espoused by Hon, and forever more errouneosly cemented the "deceleration" as the indication of hypoxia, prompting unnecessary interruption of labor mostly by Cesarean, being oblivious to the Fetal Oxygen Brain Sparing Mechanism. She may have done a great service to the reputation and the fortune of Dr. Hon, but she cemented in the minds of all practitioners who manage labor a false and unproven assumption. It highlighted a travisty, not genious.