Too Hungry to Wait: What SNAP and WIC Cuts Mean for Pregnant Women

The Responsibility Clause - When a political shutdown meets a biological reality, the ones who suffer most are those carrying the future.

Bagels, Cream Cheese, and Bureaucracy

When I directed the high-risk pregnancy clinic in Harlem, I used to pick up enormous bags of fresh bagels and tubs of cream cheese on clinic mornings. Our waiting room smelled like a New York bakery. Every week, we fed women who were hungry, tired, and often anxious about whether they’d make it through the month. Around Thanksgiving, we handed out frozen turkeys, a small gesture that turned a prenatal appointment into something hopeful.

Then the city health department stepped in. The tubs of cream cheese, they said, were “unhygienic.” We could only serve single-use packets, and each bagel had to be wrapped individually. The food still filled bellies, but something vital was lost — the sense of community, of breaking bread together, of dignity without paperwork.

That experience taught me something simple: feeding pregnant women is medicine. Bureaucracy rarely understands that. And as the SNAP and WIC cuts take effect, it’s hard not to remember how easily good intentions get strangled by red tape.

Tonight, federal funding for SNAP and WIC stops.

For the 42 million Americans depending on food aid, this is not a policy debate; it’s tomorrow’s breakfast. Among them are roughly 700,000 pregnant women who receive WIC benefits each month. They were promised help in buying milk, eggs, fruits, vegetables, and formula, the simplest building blocks of a healthy pregnancy. Now, the nation’s safety net has holes large enough for expectant mothers to fall through.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) together form the nutritional backbone for low-income families. SNAP feeds the household. WIC protects the vulnerable, the pregnant woman, the unborn child, and the newborn. When both are cut off at once, this isn’t just “belt-tightening.” It’s state-sanctioned malnutrition.

Who is affected

In 2025, about 6.6 million people were served monthly by WIC:

700,000 pregnant women

4 million children under 5

1.9 million infants

At the same time, over 40 million Americans relied on SNAP for groceries. Many pregnant women receive both. The overlap is enormous, around half of all WIC participants are also on SNAP. So when SNAP funding halts, and WIC follows, roughly 350,000 pregnant women may immediately lose or see interruptions in food access.

For a pregnancy, even a few weeks of food insecurity can matter. Maternal undernutrition increases the risk of preterm birth, low birthweight, anemia, and developmental delays. These are not abstract risks. They show up as NICU admissions, school struggles, and lifelong health inequities.

The ethical cost

Pregnancy doesn’t wait for Congress. Biology keeps moving forward, even as politics grinds to a halt.

The ethical failure here is not simply that benefits have been cut, but that the timing makes the impact cruelly precise. The third trimester, when calorie and iron needs are highest, is when many women will feel these losses most sharply.

This is what happens when governance forgets physiology. Legislators can debate “budget priorities.” Fetuses can’t. When we talk about being “pro-life,” we must ask: whose life are we protecting if we withhold the food that sustains it?

How hospitals and doctors can help their pregnant patients

Clinicians can’t refill WIC cards, but they can still act. Hospitals, obstetric offices, and community clinics should treat this cutoff as an urgent public health emergency. Practical steps include:

Screen for food insecurity at every visit. Add a one-line question: “Do you have enough food for the next week?” Even a brief conversation can uncover silent hunger.

Build a local referral list. Partner with community food banks, religious centers, and nonprofits that offer groceries, diapers, or meals for pregnant women.

Create “nutrition continuity kits.” Hospital social work departments can coordinate low-cost bundles (beans, rice, oats, prenatal vitamins) through donations or local grants.

Educate through prenatal classes. Include short modules on affordable meal planning, food safety, and cooking basics, with printed guides or QR codes for recipes.

Use hospital cafeterias wisely. Offer discounted or free healthy meals to admitted or outpatient pregnant women during the shutdown period.

Track outcomes. Record maternal weight loss, anemia rates, or preterm labor cases linked to food insecurity to strengthen the evidence base for advocacy.

In a system where food is medicine, clinicians must sometimes become pharmacists of nourishment.

What our professional organizations can do

If hospitals are the frontline, our national societies are the amplifier. Professional leadership can make the invisible visible by reframing this as a maternal safety emergency, not a welfare story. Here’s how:

Issue joint statements. ACOG, SMFM, AWHONN, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Nurses Association should release coordinated alerts emphasizing that nutrition support is essential prenatal care.

Mobilize emergency communication. Encourage members to screen for food insecurity, post verified local resources, and share updates about available state WIC funds.

Engage policymakers directly. Advocate for immediate restoration of SNAP and WIC funding as a maternal health measure, not a partisan issue.

Provide guidance on documentation. Offer templates so clinicians can record food insecurity as a social determinant of health in the medical record, strengthening future research and policy arguments.

Fund local interventions. Create microgrants for clinics or residency programs to supply emergency food or nutrition vouchers to pregnant patients.

Educate the public. Use professional platforms and social media to correct misinformation — emphasizing that WIC is not a “handout” but a proven, evidence-based public health intervention that reduces infant mortality and health care costs.

When professional organizations speak clearly, legislators listen differently. Silence in moments like this is not neutrality. It is complicity in preventable harm.

How to eat well with less: the survival science of affordable nutrition

When every dollar matters, nutrition becomes math. For pregnant women suddenly losing SNAP or WIC, survival depends on stretching food, not skipping meals. These are small but powerful shifts that preserve health on a shoestring:

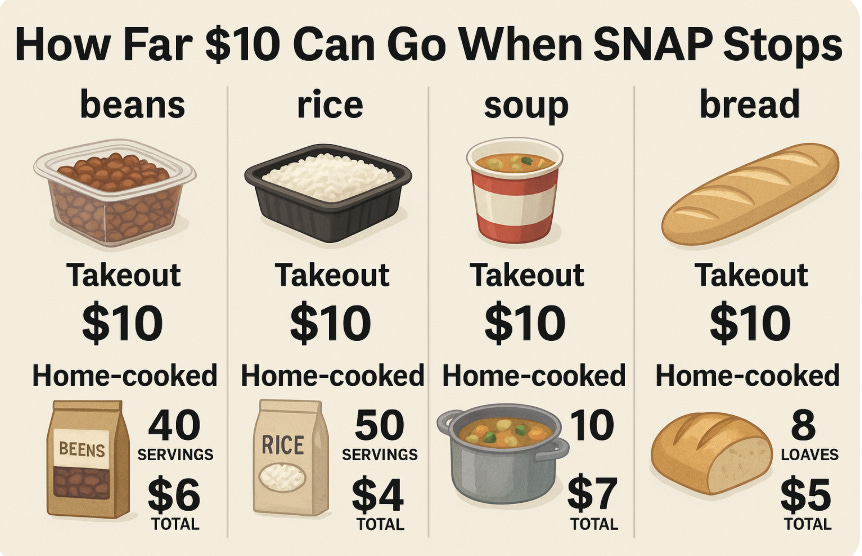

1. Cook at home. Every meal saved is money saved.

Home-cooked meals cost about one-third as much as eating out. A $10 takeout meal can often be replaced with a $3 home-cooked version. Soups, rice dishes, stews, and casseroles stretch ingredients, and leftovers can be frozen for quick meals later in pregnancy when energy is low.

2. Choose versatile, low-cost staples.

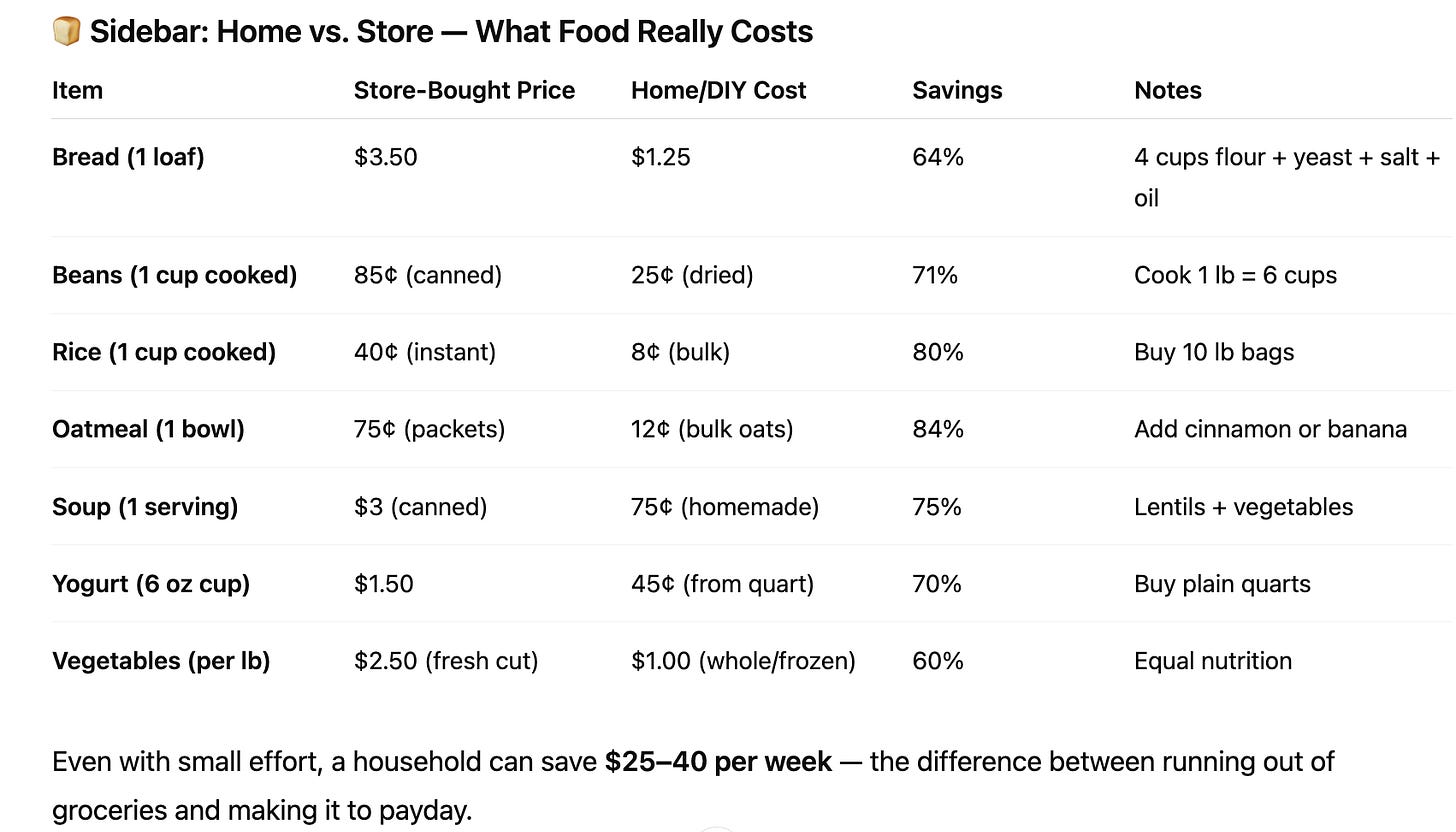

Beans and lentils: Dried beans cost about $1.50 per pound and yield six cups of cooked beans, about $ 0.25 cents per cup. Canned beans cost $1.25–$1.75 per can and yield about 1.5 cups, $ 0.80 cents per cup. That’s a fourfold price difference. Soak and cook dried beans in batches; freeze them in one-cup portions.

Rice: Brown rice and white rice both provide filling calories. Buying a 10-pound bag for $8 costs 8 cents per serving, compared to $2 pre-cooked cups at 10 times the cost.

Oats: A pound of oats ($1.30) makes about 11 servings of oatmeal, a 12-cent breakfast. Add banana slices or cinnamon for flavor.

Eggs: Still one of the most affordable proteins at ~15 cents per egg. Two eggs and toast make a nutrient-rich breakfast under 50 cents.

Frozen vegetables: Cheaper than fresh and often just as nutritious. A 12-ounce bag (~$1.20) can last for three meals.

3. Bake bread — it’s not just old-fashioned, it’s smart economics.

A store-bought loaf averages $3–$4. Baking at home costs under $1.50 per loaf using basic ingredients (flour, yeast, salt, water, a bit of oil). Homemade bread also provides better satiety and avoids additives.

If you lack an oven, many recipes use a skillet or slow cooker. Kneading dough is optional, time and heat do the work.

4. Prioritize nutrients, not marketing.

Buy whole carrots, potatoes, onions, and apples instead of pre-cut or packaged versions. A 3-pound bag of apples for $4 yields a week of fruit servings, compared to $1.50 for a single pre-sliced pack. Avoid sugary drinks and “snack packs”, they eat budgets and offer little nourishment.

5. Make protein affordable.

Canned tuna or salmon: about $1 per 3-ounce serving, rich in protein and omega-3s.

Peanut butter: ~10 cents per tablespoon. A spoonful adds protein to oatmeal or fruit.

Chicken thighs: cheaper and more flavorful than breasts; can be roasted and stretched across meals.

Lentil soup: a pot of lentils, carrots, and onions feeds four for under $3 total.

6. Compare unit prices.

SNAP and WIC or for that matter many other shoppers often overlook the price per ounce listed on shelf tags. It’s the easiest way to find savings. A large container of yogurt or cereal can be half the price per ounce compared to single servings.

7. Limit waste.

Freeze leftovers. Save vegetable scraps for broth. Use stale bread for toast or crumbs. Every ounce saved is another meal gained.

I think about this often because I grew up in a family that knew what scarcity felt like. My parents came out of the war with nothing. To save money, we went to the green market at the end of the day when prices dropped and the sellers wanted to clear the stalls. They gathered bruised but perfectly good vegetables, and stopped by the butcher for free bones that still had bits of meat on them. They even wento restaurants at the end of the day to ppick up food before it was being disregarded. At home, those bones together with the vegetable we did not peel to increase nutrition became soup, the kind that fed you twice, once through the warmth, once through the memory that you could make something from almost nothing. That lesson stayed with me in medicine: frugality is not failure, it is survival with dignity.

What this moment reveals

Cutting off food aid for pregnant women is not fiscal discipline. It is economic shortsightedness. Every dollar spent on WIC saves about $2.50 in future health costs, mostly by preventing preterm birth and infant hospitalization. That’s not charity; it’s preventive medicine.

Yet the immediate effect of today’s cutoff is not an accounting shift. It’s a moral regression. It punishes those least able to vote, lobby, or even speak: unborn children.

A reflection

The late psychologist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in 2002 for showing how humans make irrational choices, especially under stress and scarcity. He taught that people don’t weigh outcomes logically, they react to fear and loss. If Kahneman were here today, he might say that America’s current response to food insecurity is a case study in “loss aversion gone wrong.” Policymakers fear political loss more than human suffering.

Kahneman believed that empathy and evidence could make us wiser decision-makers. He would remind us that pregnant women are not an “interest group” but the literal carriers of our collective future, and starving them of basic nutrition is not just unwise policy, it’s unethical governance.