The Year After Birth: What We Still Miss

These postpartum complications account for most morbidity in the first year—and how to diagnose and manage them before they become crises.

The postpartum year remains one of the most dangerous periods in a woman’s life. The recent AJOG systematic review by Ke et al. (2025) “Frequency and timing of complications within the first postpartum year in the United States and Canada: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” pooled over 246 million deliveries in the United States and Canada and catalogued 41 distinct complications. Anxiety, depression, hypertension, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and hemorrhage topped the list, followed by PTSD, surgical infections, severe maternal morbidity, venous thromboembolism, sepsis, cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction, and mortality. More than half of maternal deaths occur between 7 and 365 days after delivery. The findings underscore what obstetricians have long observed: the “fourth trimester” is an illusion if clinical vigilance ends at 6 weeks.

1. Postpartum Anxiety

Diagnosis requires validated screening tools such as the GAD-7 or STAI, ideally administered during each postpartum visit or via telehealth. Symptoms, excessive worry, insomnia, or somatic agitation, often mimic physiologic postpartum changes. Management includes cognitive behavioral therapy as first line, SSRIs when moderate or severe, and referral for psychiatric evaluation if comorbid depression or OCD is present.

2. Postpartum Depression

Screen with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS ≥ 10 suggestive). Distinguish transient “blues” from sustained anhedonia or suicidal ideation. Early intervention with psychotherapy, social support, and if needed SSRIs such as sertraline, markedly reduces relapse and suicide risk.

3. Postpartum Hypertension

Diagnosis relies on blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mm Hg on two readings after delivery, even in women without antepartum disease. Evaluate for preeclampsia with labs and urine protein. Treat persistent hypertension with oral labetalol or nifedipine and ensure home BP monitoring with follow-up within 72 hours of discharge.

4. Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder

Postpartum OCD presents with intrusive thoughts of infant harm and compulsive checking, not psychosis. The Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale helps confirm the diagnosis. SSRIs and exposure–response prevention therapy are effective; hospitalization is reserved for functional impairment or comorbid depression.

5. Postpartum Hemorrhage

Quantified blood loss > 1 L defines PPH. Prompt diagnosis requires continuous assessment and use of calibrated drapes or gravimetric weighing. Treatment is immediate uterotonic administration (oxytocin, misoprostol, or carboprost), bimanual massage, tranexamic acid, and surgical or interventional radiologic control if bleeding persists.

6. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Suspect when women report flashbacks, hyperarousal, or avoidance linked to birth events. Screen with the PTSD Checklist (PCL-5) at postpartum or lactation visits. Early trauma-focused CBT and, when indicated, SSRIs improve recovery and maternal-infant bonding.

7. Surgical or Wound Infection

Typically occurs within 6 weeks, presenting with erythema, discharge, or fever at incision or perineal repair sites. Diagnosis is clinical, supported by wound cultures when needed. Broad-spectrum antibiotics targeting skin and anaerobes, with drainage of abscesses, remain standard.

8. Severe Maternal Morbidity (SMM)

Defined by CDC criteria, SMM includes transfusion, mechanical ventilation, or organ failure. Any readmission or emergency visit within 42 days warrants review for unrecognized SMM. Prevention hinges on early identification of hypertension, hemorrhage, and infection before deterioration.

9. Venous Thromboembolism (VTE)

Clinical signs include unilateral leg swelling, dyspnea, or chest pain. Diagnosis relies on Doppler ultrasound or CT pulmonary angiography. Anticoagulate with low-molecular-weight heparin for at least 6 weeks postpartum and address risk factors such as immobility and cesarean delivery.

10. Sepsis

Defined as infection with organ dysfunction; warning signs are fever, tachycardia, and hypotension. Obtain cultures and lactate immediately. Management follows the sepsis bundle: early broad-spectrum antibiotics, IV fluids, and source control, typically uterine evacuation or drainage.

11. Peripartum Cardiomyopathy

Suspect in women with new heart failure symptoms within 5 months postpartum. Echocardiography showing LVEF < 45% confirms diagnosis. Treat with standard heart-failure regimens (diuretics, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors if not breastfeeding) and counsel on future pregnancy risks.

12. Acute Myocardial Infarction

Though rare, postpartum MI presents with chest pain, dyspnea, or syncope; spontaneous coronary artery dissection is common in this group. Diagnosis requires ECG and troponin testing. Management is multidisciplinary with cardiology: aspirin, beta-blockers, and revascularization when indicated.

How to Fix the Postpartum Gap

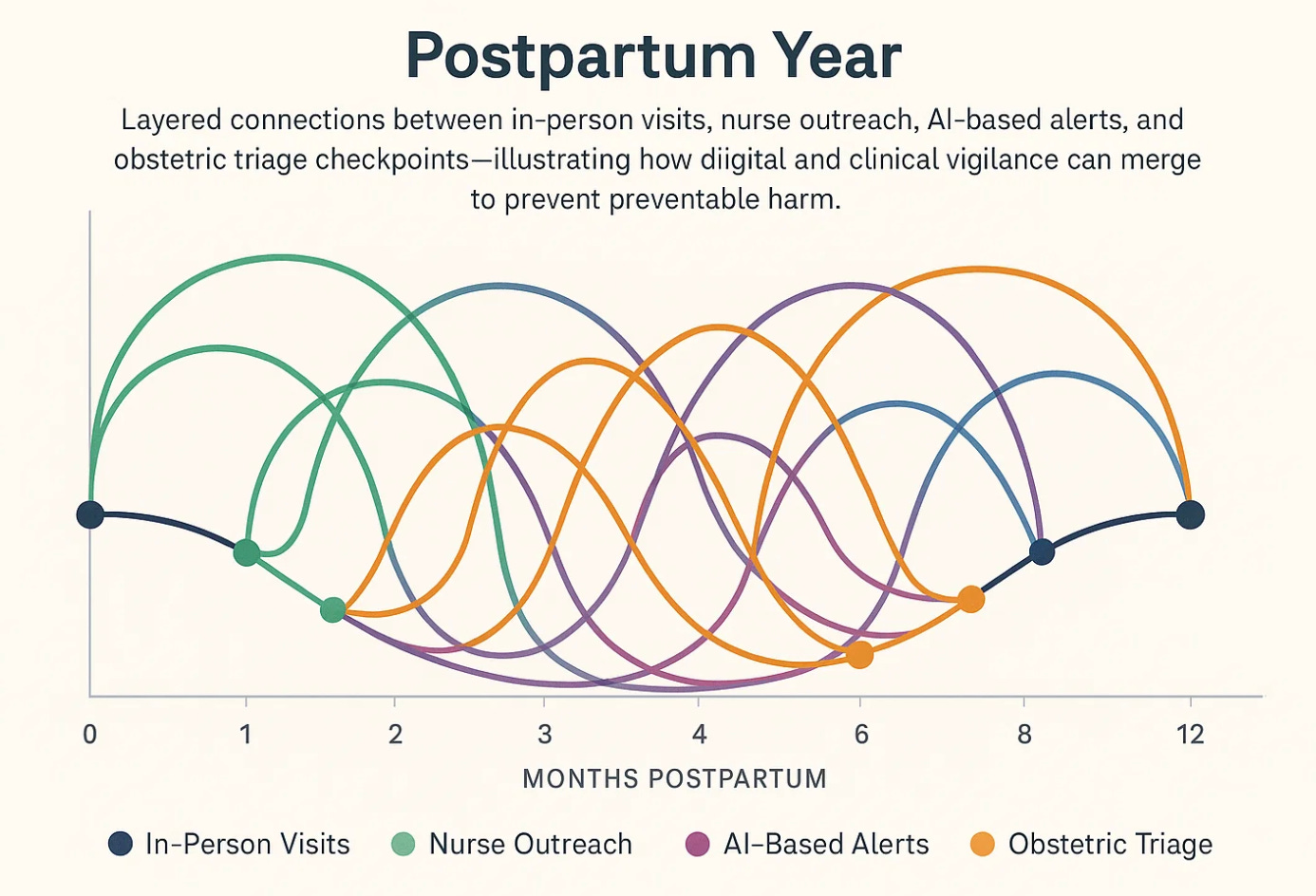

Obstetric care remains structurally front-loaded toward labor and delivery. Once discharged, many women lose direct access to their obstetric team, while labor and delivery units often refuse readmissions after one or two weeks. The result is a vacuum in care exactly when delayed hypertension, infection, and cardiomyopathy are most likely to emerge. We have built a system optimized for birth, not for recovery. The six-week visit is a relic of an era when postpartum deaths were undercounted and maternal follow-up was viewed as optional. The data from Ke et al. show that half of all maternal deaths occur after this arbitrary cutoff. The gap is not clinical—it is architectural, cultural, and ethical.

A modern maternal care model must acknowledge that the postpartum year is an extension of pregnancy, not its aftermath. The structures of obstetric practice should evolve to match the time course of risk rather than historical convenience.

1. Postpartum Nurse Outreach

Every patient should receive a home or virtual nurse visit within three days of discharge and again at two weeks, regardless of delivery type. Nurses are uniquely positioned to identify blood pressure spikes, wound issues, mental health deterioration, or early cardiopulmonary symptoms. Home BP measurements, mood screenings, and brief physical checks can prevent emergency readmissions. These visits should not be “optional services” but reimbursable components of obstetric care.

2. Dedicated Obstetric ER or Triage

Hospitals should maintain a postpartum triage service within Labor & Delivery for at least six weeks, preferably twelve, staffed by obstetric clinicians. These patients should not be diverted to general emergency departments where postpartum physiology and complications are poorly understood. The same vigilance used for antepartum triage must apply postpartum. Cardiomyopathy, pulmonary embolism, or late hemorrhage should trigger an obstetric code, not a generic chest pain protocol.

3. Integrated Surveillance System

Electronic medical records must automatically flag any postpartum readmission, ER visit, or urgent care encounter within twelve months of delivery and alert the original obstetric team. This continuity is essential for identifying delayed morbidity clusters and system failures. Without feedback loops, learning never occurs. Surveillance should be proactive, not forensic.

4. Multidisciplinary Continuity

Obstetricians should remain the central coordinators of maternal health through the first postpartum year, working in partnership with psychiatry, cardiology, and primary care. The notion that postpartum care “transitions” after six weeks ignores the overlapping medical and psychological sequelae of pregnancy. Shared care models—co-located clinics or virtual multidisciplinary rounds—can close this divide.

5. Patient Education and Empowerment

Every discharge should include clear, standardized information on warning signs—chest pain, dyspnea, headache, heavy bleeding, fever, or mood changes—translated into multiple languages and delivered both in print and digitally. Women should know precisely whom to call and where to go, day or night. Education should be reframed as risk communication, not reassurance.

6. Extend Accountability Beyond Delivery

Professional societies and hospital systems should redefine “maternal outcome” to include morbidity and mortality up to one year postpartum. Obstetric quality metrics that stop at discharge perpetuate blind spots. Performance indicators should reward early blood pressure rechecks, completed mood screenings, and prompt postpartum follow-up, not just cesarean rates.

7. Access to a Postpartum AI Information System

Artificial intelligence can become a crucial safety bridge between home and hospital. A secure, clinician-supervised AI platform could provide personalized reminders, interpret patient-reported symptoms, flag abnormal vital signs, and direct urgent concerns to the correct level of care. Such systems can integrate EMR data, home blood pressure logs, and wearable device inputs to identify risk trajectories before deterioration occurs. Instead of replacing clinicians, AI should function as an extension of vigilance—offering real-time triage, education, and continuity for every woman, regardless of geography or insurance. A well-designed postpartum AI companion could ensure that no symptom goes unnoticed between visits.

Reflection

Postpartum complications are not rare exceptions but predictable extensions of pregnancy physiology. Every week after birth remains within the obstetric domain of responsibility. The six-week boundary is an administrative convenience masquerading as clinical truth. Ke et al. have provided the evidence; what remains is structural reform. The postpartum year must be treated as part of maternity care, not a handoff to another system.

Safety in obstetrics should not end when the placenta is delivered. It should culminate in a healthy, supported mother one year later—monitored, counseled, and connected through both human and digital care systems. Anything less is unfinished medicine.

What an important piece, a reframing to uphold the fourth trimester. Mental Health Wellness surveillance is crucial here as systems have underplayed how vital continuity and diagnosing are. We can meet the client where they are certainly.