The Truth About Due Dates: Why 40 Weeks Is a Myth

Did you know that only about 5% of babies are actually born on their predicted due date

Every pregnant woman gets asked the same question: “When’s your due date?” But here’s the secret—this date is more of a guess than a guarantee. In fact, only about 5% of babies are actually born on their predicted due date.

Where Did 40 Weeks Come From?

The original Naegele’s rule, described by the German obstetrician Franz Karl Naegele in 1812, was a simple arithmetic method to estimate the due date. He proposed adding one year, subtracting three months, and then adding seven days to the first day of the woman’s last menstrual period (LMP). This calculation assumes a fixed menstrual cycle of 28 days, with ovulation occurring precisely on day 14, and leads to an average pregnancy length of 280 days (40 weeks) from LMP. While widely adopted, the Naegele rule has limitations: it does not account for variations in cycle length, ovulation timing, or the biological variability in human gestation.

More accurate physiological dating recognizes that pregnancy length is better measured from conception (fertilization/ovulation) rather than the LMP. On average, human gestation lasts about 266 days (38 weeks) from fertilization, which corresponds to 280 days from the LMP only when ovulation reliably occurs on cycle day 14. In reality, ovulation can occur earlier or later, making the LMP-based calculation imprecise for many women, particularly those with irregular cycles. This distinction matters clinically: a pregnancy dated strictly by Naegele’s rule may lead to misclassification of preterm or post-term status, unnecessary inductions, or delayed recognition of prolonged gestation.

For this reason, modern obstetrics often prefers to use a combination of first-trimester ultrasound dating and the physiologic benchmark of 266 days from ovulation/fertilization, which aligns better with embryologic development. Naegele’s rule remains a convenient heuristic, but it should be corrected or refined with more accurate methods when possible, as precision in gestational dating has significant implications for clinical care, decision-making, and outcomes.

Gestational age definitions (ACOG/SMFM):

Very preterm: <32 weeks

Preterm: 32 0/7 – 36 6/7 weeks

Early term: 37 0/7 – 38 6/7 weeks

Full term: 39 0/7 – 40 6/7 weeks

Late term: 41 0/7 – 41 6/7 weeks

Postterm: ≥42 0/7 weeks

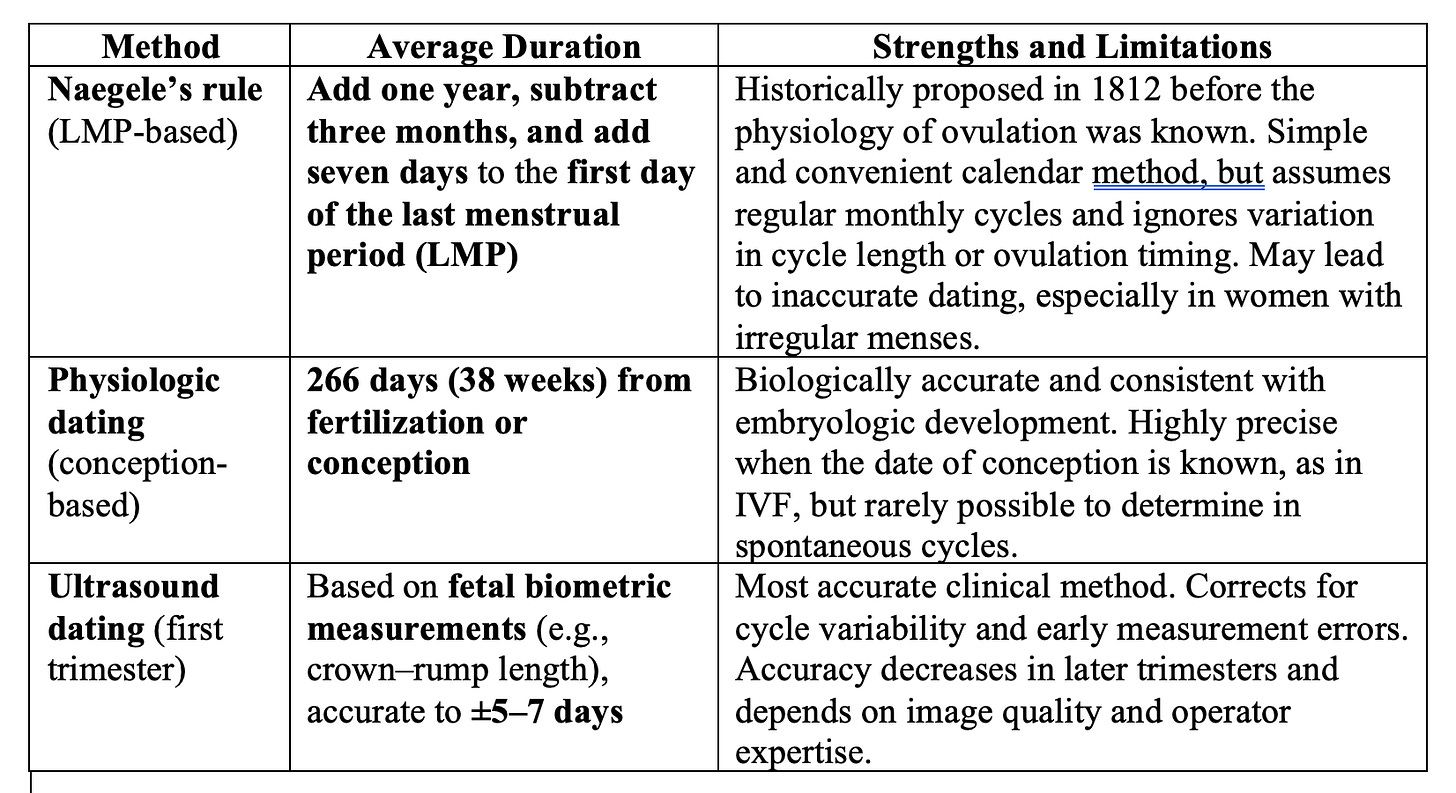

Comparison of Pregnancy Dating Methods

In reality, pregnancy length is more precisely about 38 weeks (266 days) from ovulation and fertilization, not 40 weeks from the first day of the last period. That extra two weeks assumes every woman has a perfect 28-day menstrual cycle with ovulation on day 14—a biological fiction for many. This small but important detail often gets overlooked, leading to confusion about when pregnancy truly begins.

Comparison of Pregnancy Dating Methods

The above table shows that there are differences in Naegele’s due date calculation and the 280-day calculation. The differences are between 0 and 3 days.

The Reality of Normal Pregnancy Length

Most pregnancies last somewhere between 37 and 42 weeks. That’s a five-week window. A baby born at 39 weeks is full-term, but so is one born at 41 weeks. Nature doesn’t follow a calendar app.

Here’s how we define the stages more precisely:

Viability: About 22 weeks—the point when a fetus has areasonable chance of survival outside the womb, though often with very high risks.

Pre-viability: Before 22 weeks

Very preterm: Less than 32 weeks.

Preterm: Less than 37 weeks.

Early term: 37 weeks 0 days to 38 weeks 6 days.

Full term: 39 weeks 0 days to 40 weeks 6 days.

Late term: 41 weeks 0 days to 41 weeks 6 days.

Postterm: 42 weeks and beyond.

Think of it like a train schedule: one train might arrive five minutes early, another ten minutes late, but both are on time. Similarly, “on time” for birth has more flexibility than most people realize.

Why This Matters Clinically and Ethically

Babies born before 37 weeks are “preterm” and have increased risks such as problems with their lungs. The early they are born, the higher te risks. Inducing labor too early, based only on the due date, can increase risks. Babies may need extra breathing support, and mothers may face longer recoveries or higher cesarean rates.

On the other hand, letting pregnancy go too far also has risks—such as stillbirth or complications from the placenta aging. The challenge for clinicians is to balance safety without treating the due date like a deadline set in stone.

This is not just medical—it’s ethical. If a doctor tells a patient “you must deliver today” only because she’s past 40 weeks, that can cross into directive counseling without strong evidence. Women deserve honesty: a “due date” is really a “due range.”

What’s New and Overlooked

Today, we have better tools. Early ultrasound is more accurate than the last menstrual period in predicting gestational age. We also know that race, maternal age, and health conditions can shift the “average” length of pregnancy. Yet, too often, we still use one outdated number—40 weeks—as if it applied equally to everyone. Twin pregnancies still have a due date of 40 weeks, but they are usually born earlier.

Practical Takeaways

Patients: Don’t panic if your baby doesn’t come on the exact day circled on your calendar. It’s normal.

Families: Support the pregnant person without pressure—“any day now” can mean weeks.

Clinicians: Be precise in language—say “around this time” instead of “your due date.” Share the concept of a due window.

By reframing the conversation, we reduce anxiety and avoid unnecessary medical interventions.

Reflection / Closing:

Maybe it’s time to retire the “due date” altogether and speak instead of a “due month.” Wouldn’t that shift both the medical culture and family expectations toward patience, honesty, and healthier outcomes?

I enjoyed this read. Thank you!