The Second Stage of Labor Is Not a Stopwatch

What AJOG’s Expert Review by Wayne R. Cohen actually says about duration, descent, and danger

The second stage of labor begins at complete cervical dilation and ends with delivery. For more than half a century, obstetrics has treated its duration as the dominant marker of safety, progress, and failure. In March 2024, the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology published an Expert Review titled “The Second Stage of Labor” by Wayne R. Cohen, MD, with Emanuel A. Friedman, MD. The review does not introduce a radical new intervention. It does something more disruptive. It exposes how modern obstetrics has misunderstood its own evidence and substituted clocks for clinical reasoning.

When AJOG publishes an Expert Review, it is meant to recalibrate practice, not decorate it. Cohen’s review does exactly that. It challenges the assumption that elapsed time defines abnormality and argues that this assumption has quietly distorted labor management, education, guidelines, and medicolegal thinking.

What Cohen actually examined

Cohen systematically reviews the physiology of second-stage labor, patterns of fetal descent, pelvic architecture, pushing techniques, epidural effects, and maternal and neonatal outcomes. He places modern practice in historical context, tracing contemporary time limits back to the 1952 report by Hellman and Prystowsky. That early work demonstrated correlations between prolonged second stage and adverse outcomes. Over time, correlation hardened into causation, and caution ossified into rigid thresholds.

Cohen shows that subsequent studies repeatedly demonstrated something inconvenient. When fetal monitoring is reassuring and descent continues, the duration of the second stage itself contributes little independent risk, particularly within the first three hours. Yet the profession continued to treat time as destiny.

Duration versus mechanism

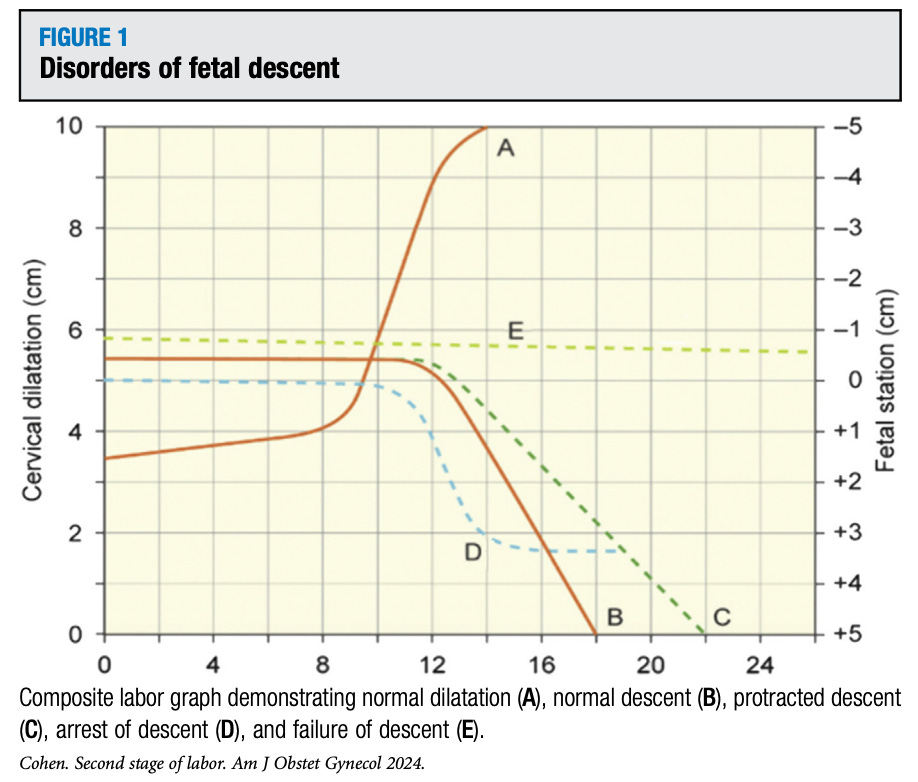

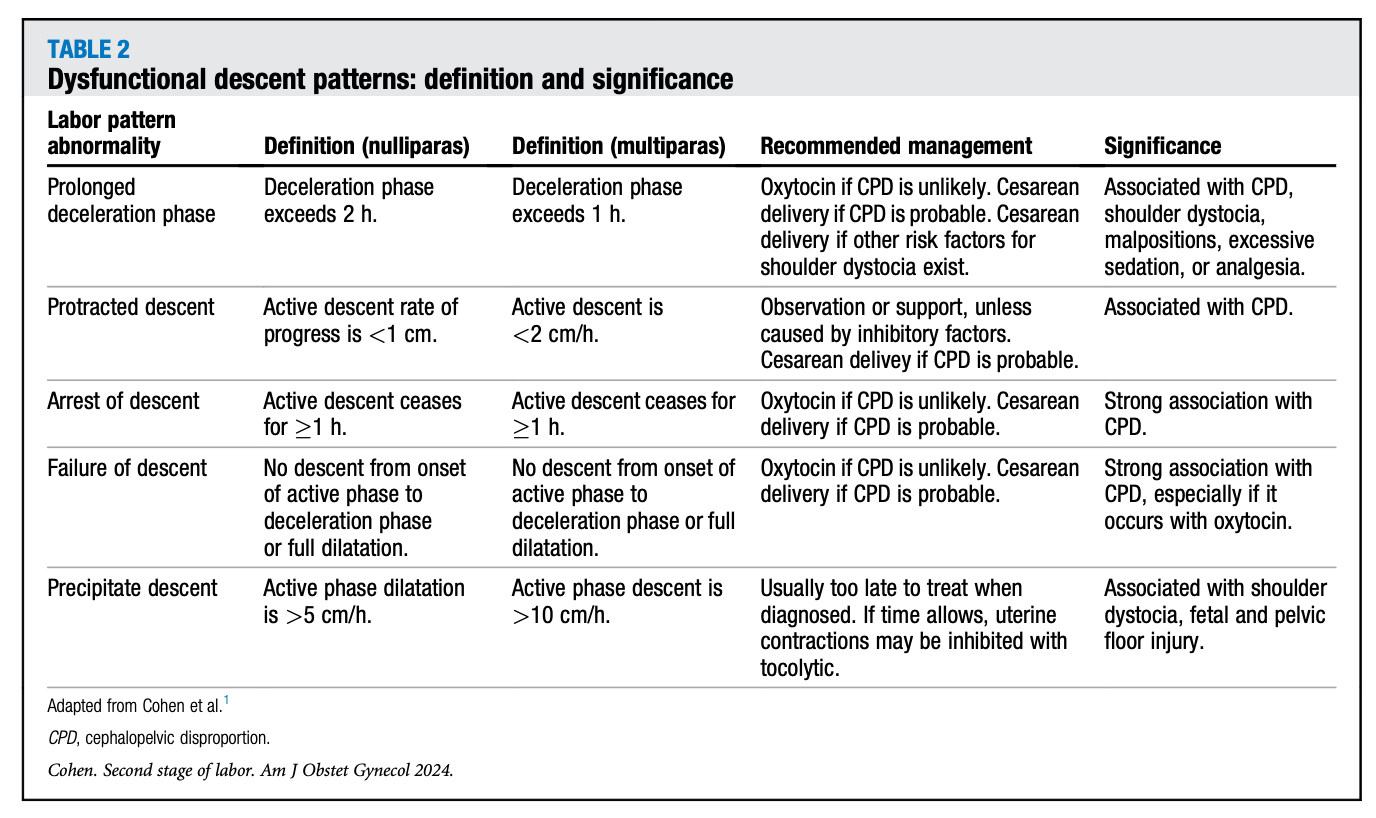

A central argument of the review is that the second stage is not a single phenomenon. It is a process driven by descent, rotation, flexion, molding, and fetopelvic relationships. A three-hour second stage with steady descent represents normal physiology. A two-hour second stage with no descent represents pathology. Grouping these scenarios together under a single time cutoff is methodologically indefensible.

Cohen emphasizes that the prognosis for vaginal delivery depends far more on patterns of descent than on elapsed minutes. This distinction is repeatedly demonstrated in the literature but rarely operationalized in guidelines or bedside decision-making.

What the evidence actually shows

The review synthesizes multiple cohort and population-based studies showing that extending second-stage duration, in line with more permissive recommendations, reduces primary cesarean delivery rates in both nulliparous and multiparous women. This finding has been widely cited to justify longer pushing.

But Cohen does not stop there. He highlights the accompanying tradeoffs. Extension of the second stage is associated with higher rates of operative vaginal delivery, severe perineal lacerations, postpartum hemorrhage, shoulder dystocia, neonatal acidemia, and NICU admission. These are not trivial outcomes, and they are not evenly distributed. They cluster in labors with unrecognized or unmanaged disorders of descent.

The key point is not that longer is better or worse. The point is that duration is not the causal variable. The underlying mechanism is.

What the evidence does not support

Cohen is explicit that the data do not support unlimited prolongation of the second stage. Very long second stages may increase the risk of pelvic floor injury, incontinence, and sexual dysfunction, although confounding factors make causation difficult to isolate. The review urges caution against enthusiasm for “very long” second stages, particularly when fetal oxygenation is compromised or descent is static.

Equally important, the data do not support reflexive intervention once an arbitrary time threshold is crossed. Both errors stem from the same flaw. Using duration as a surrogate for physiology

.Why modern practice drifted

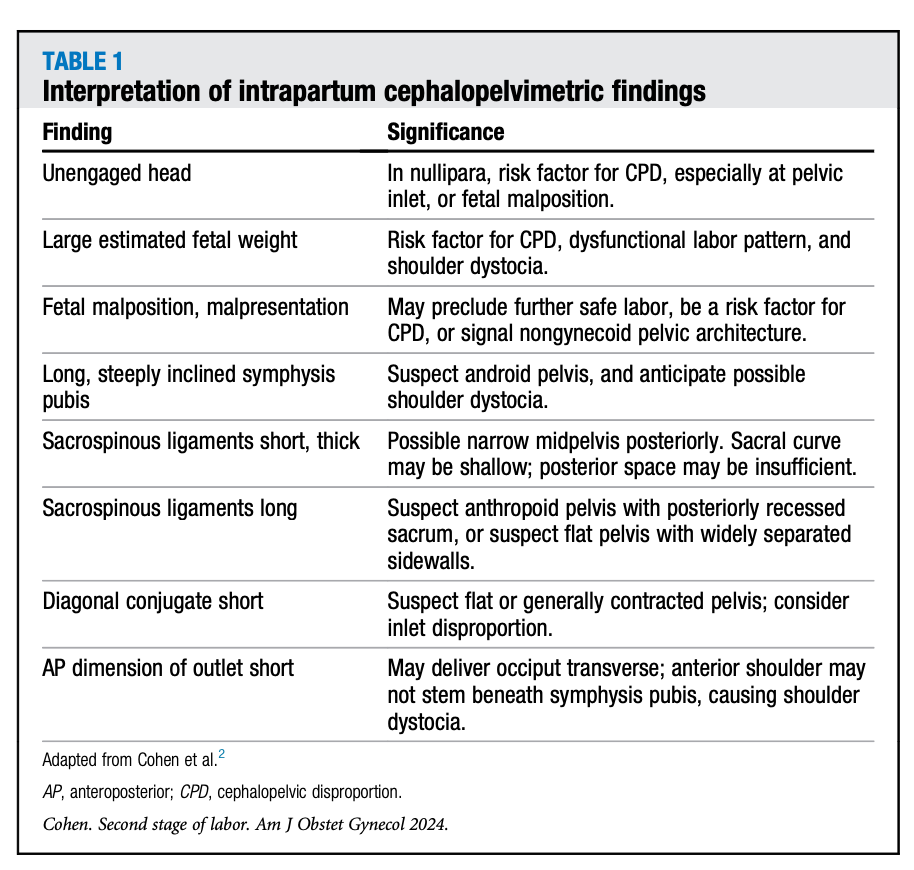

Cohen identifies a quiet but consequential shift in obstetric training. Skills such as clinical cephalopelvimetry, nuanced assessment of descent, and interpretation of pelvic architecture are no longer emphasized. Duration is easy to measure, easy to document, and easy to defend. Descent requires experience, judgment, and accountability.

Ultrasound assessment of fetal descent may offer promise, but Cohen is clear that imaging should complement, not replace, skilled clinical examination. The loss of these skills has made time-based rules attractive and dangerous.

The guideline problem

Cohen notes that recent SMFM and ACOG recommendations suggest extending second-stage limits but fail to specify clear physiologic criteria or evidentiary foundations. This leaves clinicians with expanded clocks but no improved framework for decision-making. The result is variability, indecision, and, too often, delayed intervention followed by rushed delivery.

Guidelines that emphasize duration without embedding descent patterns risk codifying imprecision. Evidence-based medicine becomes checkbox-based medicine.

Ethical implications

The ethical cost of time-based thinking is substantial. Intervening solely because a threshold has been crossed, despite reassuring fetal status and ongoing descent, undermines beneficence. Waiting solely because “more time is allowed,” despite arrest of descent and evolving fetal compromise, undermines nonmaleficence.

Cohen’s review reframes shared decision-making. Patients cannot meaningfully consent to plans based on clocks alone. Ethical care requires explaining the actual determinants of safety and risk, even when they are complex.

Practical lessons from the AJOG review

First, prolonged second stage should prompt evaluation, not reflex. Second, serial assessment of station, position, rotation, and molding must return to the center of care. Third, documentation should reflect trajectory, not just duration. Fourth, operative vaginal delivery and timely cesarean remain critical skills, not failures, when physiology declares itself.

Reflection

Cohen’s AJOG Expert Review does not argue for patience or intervention. It argues for discernment. It asks obstetrics to stop outsourcing judgment to a stopwatch and to reengage with the biology it claims to manage. When evidence shows that time is a blunt instrument, continuing to rely on it is not cautious practice. It is intellectual inertia. And inertia, in medicine, has a body count.

There is certainly truth to the need for clinical assessment as opposed to arbitrary time limits but like breech delivery, very few left to teach it to this generation