The Placenta We Pretend Not to See

A new American Journal of ObGyn (AJOG) paper reminds us that obstetrics still overlooks the most essential organ of pregnancy. And in life.

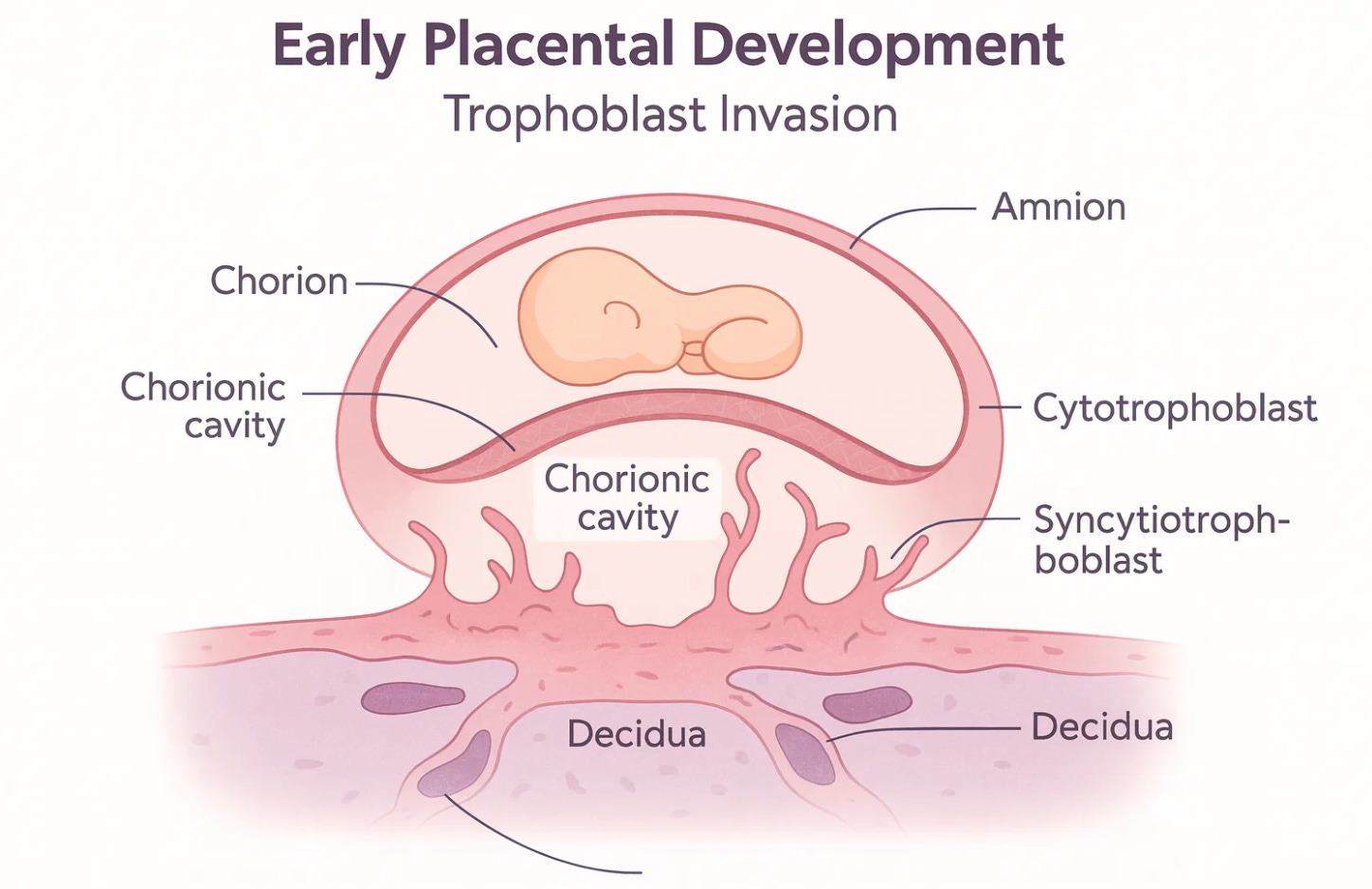

Everyone in obstetrics talks about the placenta. Very few actually study it with the seriousness it deserves. A recent AJOG paper called “Formation of the placental membranes and pathophysiological origin of associated great obstetrical syndromes” examines the formation of the placental membranes and their relationship to the great obstetrical syndromes. It offers an opportunity to rethink how we approach this organ clinically, scientifically, and ethically. The paper reviews how the amnion, chorion, and decidua develop, how these layers coordinate to protect the fetus, and how disruptions in early placental biology may set the stage for preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, and placental abruption. It highlights something the field has been reluctant to acknowledge. Placental pathology is not a postmortem exercise. It is an early biological narrative that shapes every pregnancy from implantation forward.

The placenta is a temporary yet biologically complex organ that forms from the fertilized egg and therefore carries the fetus’s genetic material rather than the mother’s.

It anchors the pregnancy to the uterus, remodels the maternal vasculature, regulates oxygen and nutrient transfer, removes fetal waste, produces essential hormones, and creates an immune environment that permits the genetically distinct fetus to survive. It is simultaneously endocrine gland, respiratory interface, metabolic engine, and immunologic shield. No other human organ performs such a broad range of functions in such a short period of time, and its proper formation determines the trajectory of the entire pregnancy.

This kind of work matters because obstetrics has a long track record of treating the placenta as an afterthought. We focus on the fetus, the mother, the delivery, the complications. The placenta is often positioned as the supporting actor rather than the protagonist. Yet the evidence tells a different story. Nearly every so called obstetrical syndrome begins with a placental problem. What the AJOG paper makes clear is that these problems are not random. They emerge from well described deviations in trophoblast invasion, vascular remodeling, immunologic balance, and membrane integrity. When these early processes fail, the clinical manifestations appear months later. By the time hypertension develops or fetal growth slows or membranes rupture prematurely, the underlying biology has been in motion for a long time.

What the New Evidence Shows

The AJOG paper offers a detailed description of how placental membranes form during early gestation. It synthesizes developmental biology, pathology, and clinical correlations. Several points stand out.

First, the interface between trophoblasts and maternal tissues is dynamic and highly regulated. Second, the membranes operate as an immunologic barrier, a structural envelope, and a signaling platform. Third, great obstetrical syndromes share common origins in early placental dysfunction.

This is not a new hypothesis. What is new is the depth of evidence linking specific membrane abnormalities to downstream pathology. The paper highlights how disruptions in membrane formation may correlate with clinical conditions such as preterm premature rupture of membranes, early-onset preeclampsia, and placental insufficiency.

By anchoring these conditions in membrane biology, the authors shift our attention toward earlier windows of vulnerability. This matters clinically because our current management strategies are often reactive. We wait for hypertension before diagnosing preeclampsia. We wait for poor fetal growth before identifying insufficiency. We wait for symptoms of preterm labor before assessing membrane integrity. The science tells us that by the time these signs appear, the foundation has already been laid.

The Placenta as the Most Important Organ No One Teaches Well

Medical students receive limited exposure to placental biology. Residents spend enormous time on labor curves, fetal monitoring, and emergency management, but relatively little time on the molecular architecture of the placenta. Many clinicians never learn the details of trophoblast differentiation or membrane fusion.

We would never tolerate this level of superficiality in cardiology. You cannot treat heart failure without understanding how the myocardium works. Yet in obstetrics we routinely manage disorders rooted in the placenta without a proportional understanding of the underlying organ. The result is predictable. We label conditions instead of explaining them. We intervene late because we lack early markers. We treat the maternal physiology without addressing the etiologic substrate.

The placenta is the only transient organ that determines the health trajectories of two patients simultaneously. It regulates oxygen transfer, nutrient exchange, immune tolerance, endocrine signaling, vascular remodeling, and waste elimination. It is, in every meaningful sense, the first organ system that fails when pregnancy goes wrong.

Why We Ignore It

There are practical reasons. Placental tissue is difficult to study in vivo. Ethical constraints limit invasive early gestational sampling. Imaging resolution remains imperfect. But some of the reasons are cultural. Obstetrics has historically centered on labor and delivery. The field grew around managing emergencies, not deciphering developmental biology. The placenta is quiet. It has no visible symptoms until it fails. It is easy to forget it, and clinicians are rewarded for solving acute problems rather than understanding upstream mechanisms.

This is beginning to change. A growing body of translational research shows that placental pathology predicts both short and long term outcomes. The AJOG paper contributes to this shift by emphasizing that membrane formation is not merely structural anatomy. It is a developmental program with clinical consequences.

The Stakes for Patients

When clinicians treat the placenta as peripheral, patients experience the consequences. Delayed diagnosis of preeclampsia, missed signs of early insufficiency, unexplained congenital anomalies linked to early developmental disruptions, and lack of precise counseling all stem from our incomplete understanding.

More importantly, ignoring the placenta contributes to inequities. Many conditions disproportionately affecting Black women, including preeclampsia and placental abruption, have roots in placental biology. Research gaps become care gaps. Care gaps become outcome gaps.

What Needs to Change

Three changes are essential.

First, placental science must be part of mainstream obstetrics education. Every resident should understand early trophoblast function as well as they understand the Bishop score.

Second, clinical care needs earlier biomarkers and better screening tools that reflect placental health rather than waiting for maternal symptoms. This requires investment in translational research and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Third, we need to treat placental pathology as a living document of pregnancy rather than a retrospective curiosity. Pathology results should not be an afterthought in postpartum rounds.

They should inform counseling for future pregnancies and family planning. A systematic placental examination should be considered essential, not optional, because it is the only organ that records the biologic history of the pregnancy in real time. Every placenta provides clues about perfusion, inflammation, infection, vascular pathology, membrane integrity, and developmental patterns that no other test can reconstruct after delivery. Routine submission to pathology would allow clinicians to identify preventable risks, understand the origins of complications, and give families clearer explanations of what happened and why. In a field that values examination of life, we cannot ignore the organ that enabled it.

The AJOG article is a reminder that the placenta is not passive. It is not background. It is the central narrative of pregnancy, and our clinical frameworks should reflect that.

Closing Reflection

If obstetrics were redesigned today from first principles, the placenta would sit at the center of every textbook, every training program, and every conversation about maternal and fetal health. The evidence is unmistakable. The question is whether our clinical culture will evolve to match the biology.