The Obstetric Intellect: Twins - Two Babies, One System And Twice the Complexity

Twin pregnancies aren’t just double the joy — they’re a live experiment in resource sharing, risk management, and the limits of medical prediction.

Everyone loves twins. The sight of two matching bassinets draws smiles in the hospital hallway, and grandparents beam as if nature has performed a small miracle just for them. But behind that joyful symmetry lies one of obstetrics’ most complex balancing acts — one uterus, two babies, and a thousand possible complications.

The Biology of Two: Not All Twins Are the Same

Let’s start with the basics. “Twins” is an umbrella term for very different biological realities. There are two main types: dizygotic (fraternal) and monozygotic (identical).

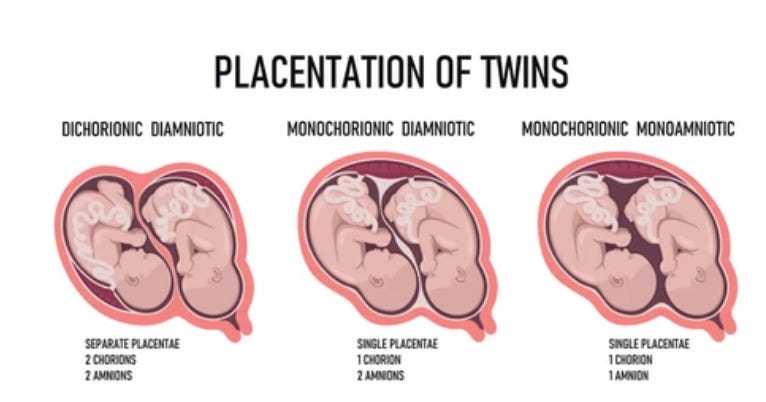

Fraternal twins occur when two eggs are fertilized by two sperm. They share a pregnancy but not genetics, any more than ordinary siblings do. Their placentas and amniotic sacs are separate — what we call dichorionic–diamniotic, or “di-di” twins.

Identical twins come from one fertilized egg that splits into two embryos. But when that split happens determines everything that follows.

If it happens within three days of fertilization, each twin develops its own placenta and sac — again, di-di.

If it happens between days four and eight, they share one placenta but have separate sacs — monochorionic–diamniotic (mono-di).

After day eight, they share both the placenta and the sac — monochorionic–monoamniotic (mono-mono).

And if the split occurs after day thirteen, it may not be complete, resulting in conjoined twins.

Conjoined Twins: A Single Beginning, Shared Lives

Conjoined twins represent one of the rarest and most challenging outcomes in all of obstetrics, occurring in roughly 1 in 50,000 to 1 in 200,000 births. They result from an incomplete division of the embryonic disc, meaning the two fetuses remain physically connected — often sharing vital organs such as the liver, heart, or brain. Types vary widely: thoracopagus (joined at the chest), omphalopagus (abdomen), and craniopagus (head) are among the most recognized forms.

Prenatal diagnosis by high-resolution ultrasound and fetal MRI now allows detailed mapping of shared anatomy, helping families and multidisciplinary teams prepare. But the ethical dimension is profound. Some cases may be surgically separable with good survival; others are not compatible with independent life. Decisions about continuation, selective reduction, or postnatal surgery often involve months of counseling among obstetricians, pediatric surgeons, ethicists, and parents — all trying to balance respect for life, suffering, and realism.

Conjoined twins remind us that biology is not binary. Even the earliest stages of life resist easy categorization, forcing medicine to confront the limits of intervention and the meaning of individuality itself.

Shared Placentas, Shared Problems

The placenta is not a quiet bystander in twin pregnancies; it’s the stage on which the entire drama plays out. When twins share a placenta, they share blood vessels, too — and that’s where the complications start.

In monochorionic twins, blood can flow unevenly between the two babies, a condition known as Twin-to-Twin Transfusion Syndrome (TTTS). One baby becomes the “donor,” sending more blood than it receives; the other becomes the “recipient,” receiving too much. Both are at risk: one for anemia and growth restriction, the other for heart failure and fluid overload.

Modern fetal medicine has developed elegant — even heroic — solutions, including laser ablation of placental vessels performed inside the womb. But early detection is critical. That’s why monochorionic twins need ultrasound every two weeks after 16 weeks, notevery month. The timing of care, not just its quality, determines survival.

Two Babies, One Clock

Fraternal twins face their own risks: higher rates of preterm birth, gestational diabetes, and preeclampsia. But their biggest challenge is space. As the uterus stretches, the body’s biological “clock” for labor can strike weeks earlier than expected.

While a single pregnancy averages 40 weeks, twins are often delivered around 36–37 weeks — and that’s the good outcome. Many arrive even earlier.

Kahneman might call this a “planning fallacy” of obstetrics: we think of “one pregnancy” as a single predictable process. Twins remind us that pregnancy is not one event multiplied by two — it’s a different physiological reality altogether.

The Management Spectrum: One Size Does Not Fit Two

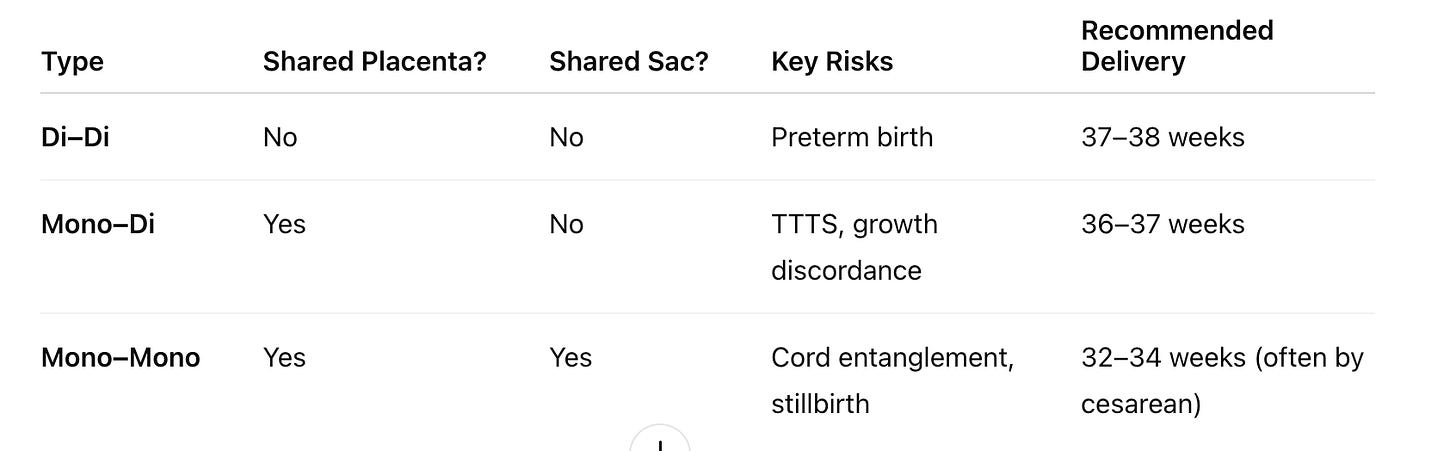

Let’s simplify the typical management plan for clarity:

But medicine rarely fits neatly into tables. Even among di-di twins, growth discordance can appear — one baby small, one large — raising difficult decisions about timing of delivery.

Intervening too early may harm both babies; waiting too long may endanger one. Every choice becomes a probabilistic tradeoff, not a certainty.

As Kahneman reminds us, humans are poor intuitive statisticians. Parents hear “10 percent risk” as either 0 or 100. Clinicians, meanwhile, often overestimate how much they can control. The truth sits somewhere in the uncomfortable middle: twin pregnancies require continuous Bayesian updating, not fixed rules.

Ethics of Two Hearts

Twin pregnancies raise profound ethical questions as well. What if one twin is growing normally and the other is failing? Do we deliver early to save one at potential cost to the other? What if TTTS is discovered late and laser surgery carries its own risk of loss?

Obstetricians live in the space between beneficence and autonomy, between probability and hope. The “right” choice isn’t a formula — it’s a conversation, renewed weekly.

Each ultrasound, each nonstress test, is not just data but dialogue: “How are both babies doing? What risks are we willing to take for each?”

When Delivery Becomes Strategy

Delivery planning for twins is a game of strategy, not routine. The question is not only when but how.

For di-di twins, if the first baby is head down and the second is not extremely large, vaginal delivery can be considered, often with expert support for internal version or breech extraction.

For mono-di twins, vaginal birth may still be possible, but close fetal monitoring and readiness for cesarean are essential.

For mono-mono twins, cesarean delivery is the norm because cord entanglement risk makes labor unsafe.

Even after delivery, vigilance continues. Twins are more likely to need NICU care, and mothers face higher risks of hemorrhage and postpartum depression. A twin pregnancy ends with two cries in the delivery room but often a long echo of medical follow-up.

The Hidden Cognitive Bias in Twin Care

Obstetricians, like all humans, are prone to normalization of risk. When you see twin pregnancies every week, danger starts to feel ordinary. Ultrasound images blur into pattern recognition: two heads, two heartbeats, one chart. The brain adapts — and sometimes desensitizes.

That’s where systems must compensate for psychology. Structured protocols, frequent checklists, and second opinions reduce the impact of human bias. The goal is not to replace judgment but to support it. As Krugman might say, complexity without structure breeds chaos — in economics and in medicine alike.

What’s New and What’s Next

Innovation continues. Artificial intelligence now assists in analyzing growth curves and Doppler patterns to predict TTTS or selective growth restriction before it’s visible to the human eye. Telemedicine allows rural patients to access subspecialty care through remote fetal monitoring.

But technology cannot substitute for trust. Twin pregnancies demand not just medical surveillance but emotional partnership. These families carry double the joy and double the fear — and need clinicians who recognize both.

Reflection: The Ethics of Multiplicity

Every twin pregnancy teaches humility. Two babies, one placenta, and nine months of shared risk remind us that medicine is not just about managing numbers; it’s about managing uncertainty.

The ethical question lingers: How do we balance the good of each twin when their interests diverge?

That’s the essence of perinatal ethics — the constant negotiation between science, empathy, and chance.