The Midwives were Right: Ignaz Semmelweis and the Midwives Who Already Knew

How a forgotten truth about handwashing exposes the hidden wisdom of midwives and the deadly arrogance of early obstetrics.

Long before Ignaz Semmelweis questioned the high maternal deaths in Vienna, the midwives of the Second Maternity Clinic were already delivering babies safely. Their outcomes were consistently better than those of the physicians in the First Clinic, not because they had a scientific explanation, but because their daily practices protected mothers from the dangers the medical establishment could not see. They did not perform autopsies, they kept cleaner routines, and they stayed close to the women in their care. Their wards were calmer, safer, and far less lethal. It was into this contrast that Semmelweis, a Hungarian physician born in 1818, stepped when he began investigating why the doctor staffed clinic had such devastating mortality. In 1847 he recognized that physicians carried infectious material from the autopsy room to the delivery bed and that handwashing in chlorinated water dramatically reduced deaths.

Semmelweis’s discovery would become one of the most important in medical history, yet the midwives had already embodied the truth he later proved. Their wisdom was ignored, his insight was dismissed, and mothers continued to die in a system that privileged male authority over observable reality.

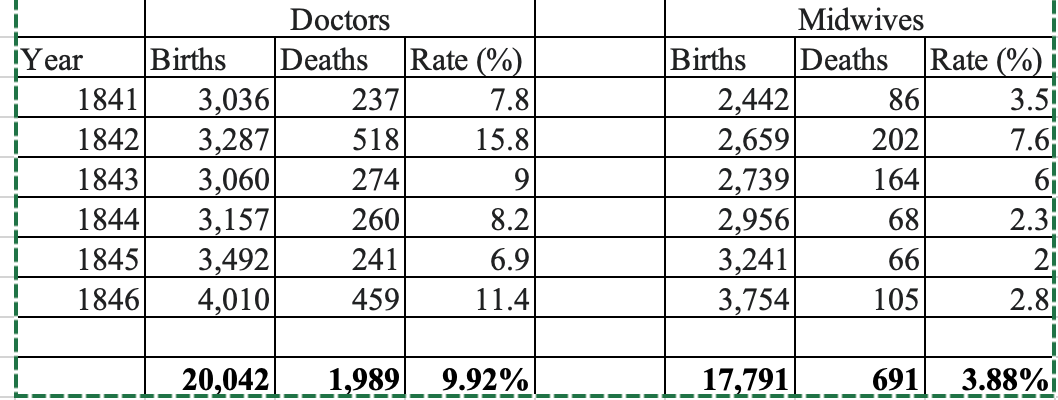

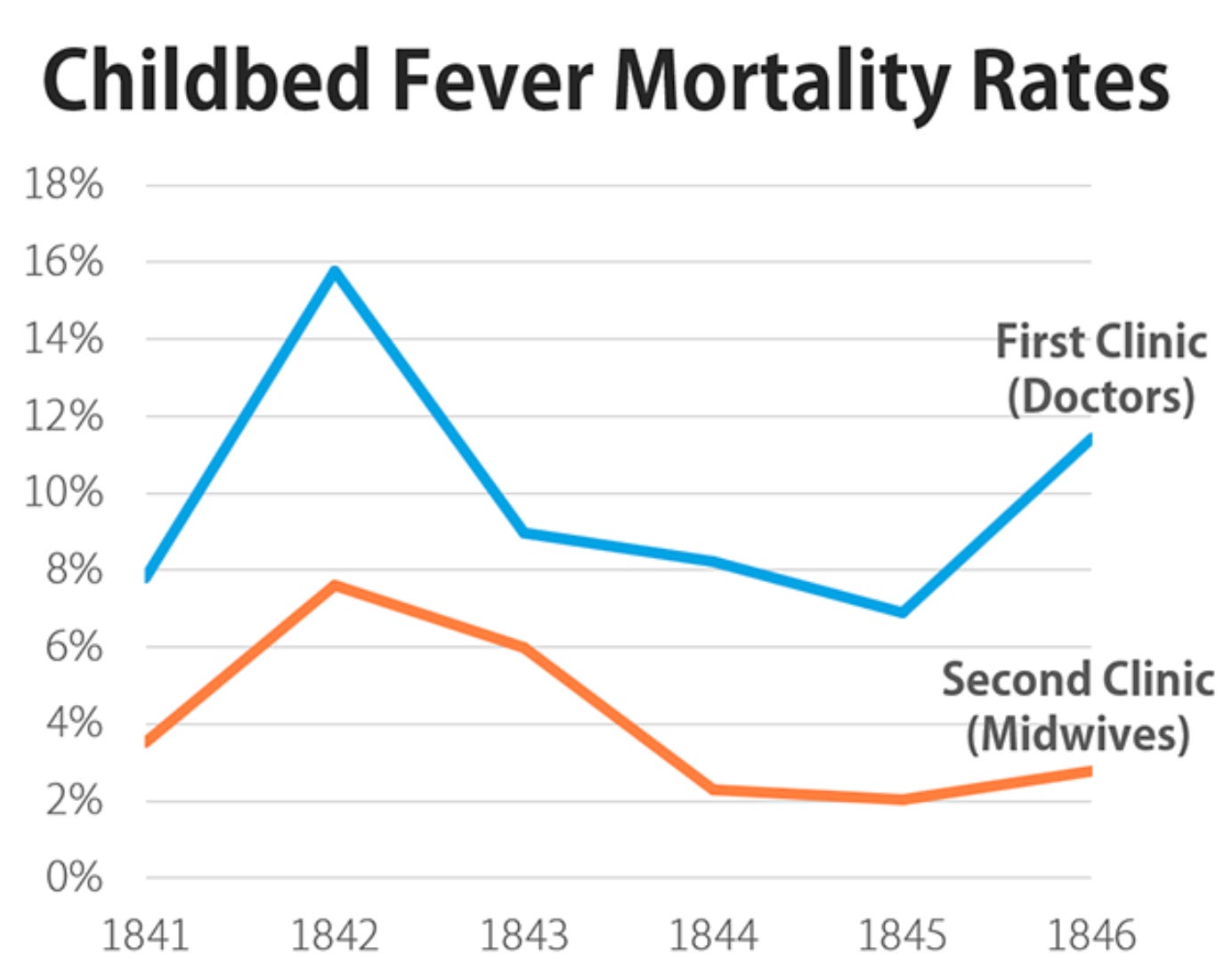

1. The Two Clinics and the Quiet Disparity

The Vienna General Hospital had two maternity clinics. In the First Clinic, run by physicians and medical students, maternal death rates from puerperal fever were shockingly high. In the Second Clinic, staffed largely by midwives, maternal death rates were far lower. Women begged to be admitted to the Second Clinic and cried when assigned to the First. Many believed the difference was a curse. In truth, the explanation was simple. Physicians performed autopsies in the morning, then delivered babies without washing their hands. Midwives did not. They were not doing autopsies. They were also, in many cases, more attentive to hygiene and practical cleanliness. They were saving lives through common sense. Yet no one credited them.

2. Midwives as the First Infection Control Specialists

Midwives in the Second Clinic practiced routines that were not formally recognized as infection control but functioned as such. They kept cleaner environments. They handled fewer invasive procedures. They washed more often because it was part of their culture and training. They listened closely to laboring women and stayed at their bedside rather than rushing between tasks. Their methods may not have been supported by scientific theory at the time, but the outcomes spoke clearly. Maternal mortality was far lower under their care. These women were the first line of defense against childbed fever. The tragedy is that their success was ignored until Semmelweis provided a mechanism that male leadership would accept

3. The Physicians and the Cost of Arrogance

Medical students and doctors resisted the idea that they were the source of infection. Many felt insulted by the suggestion. The notion that they could transmit disease with their hands challenged their authority. It challenged the hierarchy. It challenged the belief that medicine was always superior to midwifery. Rather than listening to evidence, they dismissed it. They dismissed the midwives. They dismissed Semmelweis. Their refusal to act prolonged a preventable epidemic of maternal death. This is one of the most painful lessons in obstetric history. The harm was not caused by lack of knowledge. It was caused by refusal to consider that women, particularly midwives, were right.

4. Semmelweis as a Bridge Between Practice and Truth

Semmelweis noticed what the mortality tables already showed. When midwives delivered babies, mothers lived. When physicians delivered babies after performing autopsies, mothers died. He connected these observations to the idea that invisible particles from cadavers were carried on hands. He introduced handwashing with chlorinated water and maternal deaths fell sharply. His insight matched what midwives’ outcomes had implied for years. The science finally supported the wisdom embedded in midwifery practice. Semmelweis’s tragedy is that he recognized the truth but could not persuade his peers to accept it. His failure reflects a system that valued authority over observation.

5. The Disappearance of Midwives From the Story

Historical accounts often describe Semmelweis as the lone hero who saw what others missed. In reality, midwives demonstrated the life saving pattern every single day. Their superior outcomes were visible, measurable, and persistent. Yet they were rarely acknowledged, much less credited. This erasure should trouble modern obstetrics. Women’s expertise was discounted because it did not come from men. Valuable insights into safety were ignored because they came from a profession considered inferior. When we retell the story of Semmelweis, we must restore the midwives to their rightful place. They embodied the practices that protected women even before a theory explained why.

6. Lessons for Modern Obstetrics

Semmelweis’s story warns us that systems can cling to harmful habits and resist corrections even when evidence is clear. It also reminds us that valuable knowledge may come from clinicians who lack institutional power. Today, midwives and nurses still see patterns in patient safety that physicians sometimes overlook. They stay at the bedside, notice early changes, and often recognize deterioration sooner. Their observations can be dismissed in hospitals where hierarchy is strong. The story of Semmelweis shows why this is dangerous. Maternal safety improves when every voice is taken seriously and when humility guides practice.

7. The Responsibility to Prevent the Next Semmelweis Crisis

Semmelweis challenged a system that preferred authority over accountability. The midwives delivered safe care without recognition. The physicians defended tradition rather than women’s lives. Modern obstetrics must be different. We have the evidence. We have the history. We have the responsibility to ensure that clinicians who notice problems are heard. We also have the responsibility to understand that infection control, safety practices, and respectful care need constant reinforcement. The next crisis will not look like puerperal fever, but the moral lesson is the same. When women die because a system refuses to change, the blame does not rest on ignorance. It rests on pride.

8. Why the Midwives Were Right

The midwives in the Second Clinic were right because their everyday practices protected women even before science could explain why. They did not perform autopsies, they moved less between contaminated spaces, and they maintained cleaner routines rooted in attentiveness rather than theory. Their safer outcomes were visible to anyone who cared to look. Yet their success was dismissed because it came from women in a profession considered inferior. The physicians’ refusal to learn from midwives reflected a deeper hierarchy that valued authority over evidence. The truth is that the midwives’ hands, habits, and bedside constancy saved countless mothers. Their overlooked wisdom is not an anecdote. It is a lesson. Safe care often begins with respect for those whose insights come from experience rather than rank. Modern obstetrics must recognize that humility could have prevented thousands of deaths and must ensure that similar lessons are not missed today.

Reflection

The story of Ignaz Semmelweis is not complete without the midwives who quietly saved mothers while the medical establishment denied its own role in harm. Their part in this history challenges obstetrics to confront hierarchy, listen to frontline clinicians, and honor the wisdom that comes from practical experience. The ethical question Semmelweis leaves us with is simple. Do we value truth enough to accept it even when it disrupts power. Patient safety depends on our answer.

Thank you for acknowledging midwives who have long helped women and really have ‘known’ much about L&D and early pp care that have slowly been ‘proven’ to be advantageous.

Curious though what was going on 1841-43 when both clinics had quite a bump ?