The Hidden Harm in Our Words: Why Obstetrics Should Abandon Ambiguous and Blaming Language

Clear vocabulary is one of the simplest and most powerful tools for patient safety. Precision in communication is not optional. It is a safety mandate with ethical weight.

1. How Routine Words Become Unexpected Sources of Harm

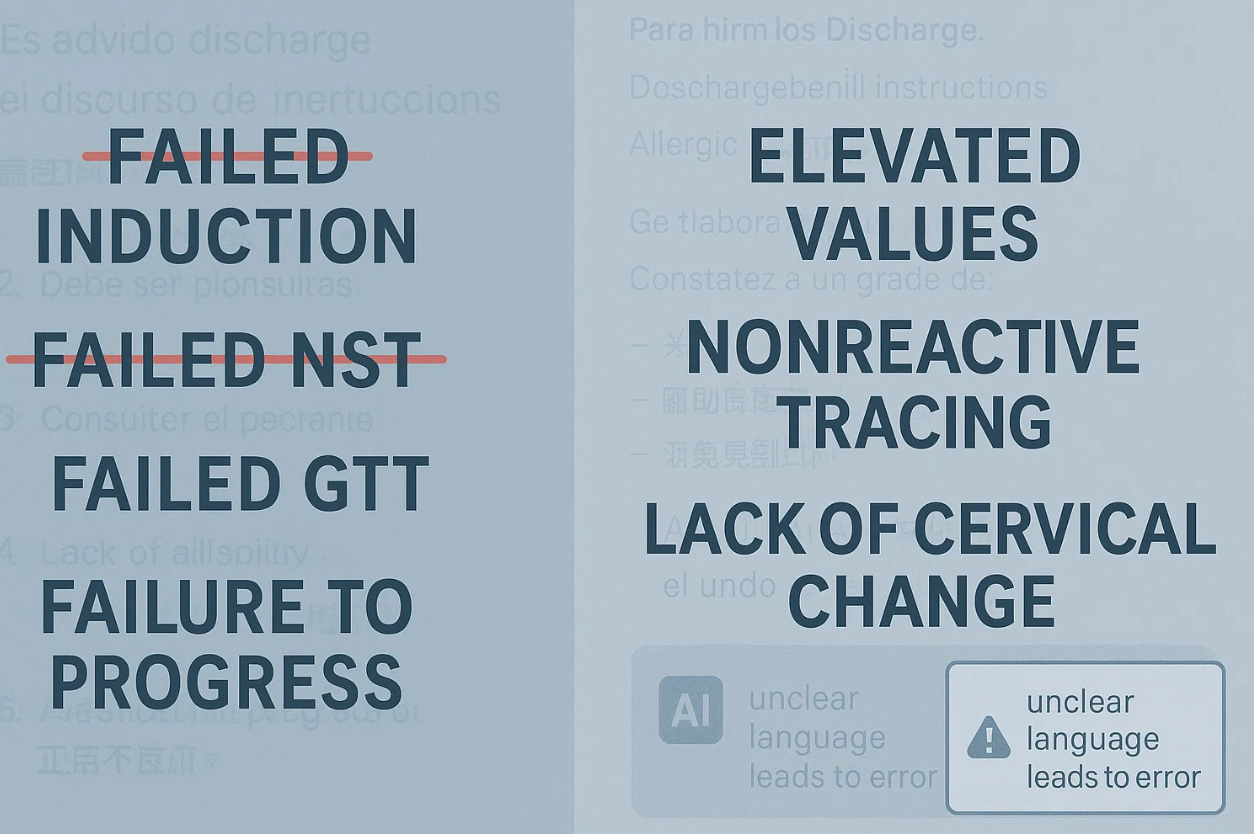

Obstetrics is filled with habitual phrases that clinicians barely notice but that patients feel deeply. A woman is told she “failed” a glucose test. Another hears she “failed to progress.” Someone else is told her baby “did not pass” the car-seat test. These terms are used casually, yet they sound like judgments about effort or character. They imply that a woman could have acted differently or performed better. That interpretation is inaccurate, but it is almost impossible for patients to avoid.

The problem grows quickly. Women often already carry anxiety about pregnancy, body image, and the health of their child. When medical language echoes blame or inadequacy, even unintentionally, patients may internalize it. They may believe they caused the result. They may feel responsible for physiology they cannot control. Emotional distress and confusion then become part of the clinical outcome.

2. Ambiguous Phrases Undermine Understanding and Safety

Beyond outright blame, obstetric communication is filled with vague shorthand. Phrases such as “nonreassuring fetal status,” “poor candidate,” “not tolerating labor,” or “borderline” have become routine. These expressions lack precision. They hide the actual clinical facts behind a label that can be interpreted a dozen different ways. They also allow clinicians to speak quickly without saying clearly what is happening.

Ambiguity is not harmless. Patients now read nearly every line of their medical records. Vague and judgment-laden terminology can erode trust and increase fear. It may also delay action. A patient who feels judged may hesitate to reach out. A patient who does not understand the situation may misunderstand the plan. Communication failures then become safety failures.

3. Clear, Descriptive Language Improves Patient Safety

The solution is straightforward. Replace vague or blaming terms with precise descriptions of what actually occurred. Instead of saying a woman “failed” a test, describe the value as elevated or above range. Instead of saying induction “failed,” specify that cervical change did not occur within the expected timeframe. Instead of “failure to progress,” describe arrest of dilation or arrest of descent. Instead of “nonreassuring,” report the actual pattern of variability and decelerations.

These phrases do not soften reality. They communicate reality. They give patients clarity, not blame. They help clinicians make more consistent decisions. And they reduce the emotional burden at a time when women deserve clarity and respect.

Importantly, the only appropriate use of the term failure is when describing system problems. Delayed responses, inadequate escalation, and poor coordination are genuine failures. Patients are not.

4. Changing Language Is Easy and Clinically Powerful

Medical vocabulary evolves continuously. Trainees learn thousands of new terms each year, more than in many foreign-language courses. Updating everyday obstetric language is not difficult. Templates can be revised. Rounding habits can be corrected. Clinical conversations can shift quickly when senior clinicians model clarity and neutrality.

Precise language is not about sensitivity. It is about accuracy. It strengthens informed consent. It improves patient understanding. It supports equity by removing judgment. Most importantly, it prevents avoidable harm. When communication is clear, patients know what is happening, what to expect, and how to participate safely in their care.

Reflection

The ethical question is simple. If a word can harm, and if a clearer alternative exists, why keep using the harmful one. In obstetrics, the safest path is the clearest one. Precision is care, not decoration.

Sorry, but if offense is not an issue as well than why even comment that the common vernacular may make the pt feel “she did not try hard enough “ with failed GTT or failed induction or failure to progress?

The mere act of mentioning AMA raises a flag to any provider reading the chart irrespective of the actual age and in and of itself is a precise definition. It automatically informs any competent practitioner what potential disorders to be on the lookout for which you claim only takes 5 more seconds to do. This being so when pt reads her chart she understands it better? But how is she to understand category 2 FHR with repetitive deep variable decelerations when reading same chart . Who exactly are we catering to with our documentation?

Proper protocol in place for years already has eliminated “non-reassuring” nomenclature but as you imply may still not be in use universally with presently accepted physician documentation. I agree with you that there is always room for improvement but reiterate that splitting hairs is not one of them.

I agree wholeheartedly with the need to improve our vocabulary in medicine. We should not be using terms like elderly or advanced maternal age. (Since the age of many pregnant women is higher these days maybe we should just refer to women under 35 as younger age pregnancies lol)

But some words like failing a test are not about the person they are speaking of the test which is itself non personal. If it makes people feel better you could say meets criteria or does not meet criteria . I think it’s a bit much to make healthcare providers have to say “ there were less than 2 accelerations in 20 minutes “.

We use the term abnormal cardiac stress test but for NST or BPP we use non reassuring which is more precise as it’s not clearly abnormal

Failed induction is accurate and does not refer to a person

So yes, some terms need to be changed but let’s not forget we use the terms to communicate efficiently with each other