The Future of ObGyn: Why I Am Writing This Series

I spent over 40 years watching obstetrics and gynecology abandon practices that should never have started. Now I want to talk about the practices that should exist but do not.

Introducing “The Future of ObGyn” series

Over the next several months, I plan to publish two series on ObGyn Intelligence:

The first, in gynecology, examines nine practices that were once standard care and are now abandoned.

The second, in obstetrics, examines eleven more.

Together, they cataloge roughly 100 practices that millions of women underwent because the profession believed they were helpful, or at least harmless, and that turned out to be neither.

Radical vulvectomy for every vulvar cancer. Routine episiotomy for every delivery. Diethylstilbestrol to prevent miscarriage. Thalidomide for morning sickness. Pubic shaving, enemas, and lithotomy position as standard labor preparation. Twilight sleep. X-ray pelvimetry. Routine electronic fetal monitoring that was supposed to eliminate cerebral palsy and did not reduce it by a single case.

These were not fringe therapies. They were the standard of care, taught in medical schools, defended by professional organizations, and performed on millions of women for decades before the evidence caught up. Some persisted for 50 years after the first data showed they were harmful. The pattern was always the same: a plausible idea, adopted before adequate testing, sustained by tradition, defended by authority, and abandoned only after the weight of evidence became impossible to ignore.

I witnessed many of these practices firsthand. I started medical school in the early 1970s. I trained in obstetrics and gynecology when DES was still being prescribed, when episiotomy was universal, when cesarean section rates were beginning their climb from 5% toward what would become 32%. I spent the next five decades delivering babies, performing surgeries, teaching residents, conducting research, and watching the field evolve. Some of that evolution was progress. Some of it was the profession finally admitting it had been wrong.

Writing those two series taught me something I had felt for years but had not articulated clearly:

The same institutional forces that kept harmful practices alive for decades are now keeping beneficial innovations out of clinical practice. The problem is not just what we did wrong in the past. It is what we are failing to do right now.

From Looking Back to Looking Forward

The “From Routine to Regret” series asked: how did we get here? This new series “The Fuuture of ObGyn” asks: where should we be going?

I am not a futurist. I am a clinician, a perinatologist, a medical ethicist, and a researcher who has spent half a century at the intersection of maternal care and medical evidence. I have delivered thousands of babies. I have performed hundreds of cesarean sections. I have taught generations of residents. I have published in peer-reviewed journals and served as a reviewer for others. I have sat on ethics committees and argued about informed consent when the concept was still unfamiliar to most obstetricians.

What I bring to this series is some technology expertise. It is mostly clinical judgment: the ability to look at a new technology, a new algorithm, a new device, and ask the questions that matter. Does this solve a real clinical problem? Is the evidence sufficient? Who benefits? Who is at risk? What are we not being told? And the hardest question of all: is the profession’s resistance to this innovation based on legitimate caution, or on the same inertia that kept us shaving pubic hair and cutting episiotomies for 50 years?

What I See Coming

After 40+ years in this field, certain things are clear to me. Some will be controversial. That is the point.

Labor induction is the most common intervention in obstetrics, and we are doing it with tools and protocols from the 1960s. Oxytocin is titrated by hand. Misoprostol cannot be removed once placed. The Bishop score, our primary prediction tool, was published in 1964 and has a specificity below 50%. Machine learning models already outperform it. A closed-loop computer-controlled oxytocin pump was patented in 1994 and never commercialized. The gap between what technology can do and what we actually do in labor and delivery is 30 years and growing.

Electronic fetal monitoring was introduced in the 1970s to prevent cerebral palsy. It did not. After 50 years of universal use, its false positive rate for predicting acidemia exceeds 99%. AI-based fetal heart rate interpretation is in development. Whether it can salvage a fundamentally flawed screening technology is an open question, and one this series will examine.

Surgical technique in gynecology has been transformed by minimally invasive approaches, robotic assistance, and enhanced recovery protocols. But the next frontier is not incremental improvement in existing procedures. It is simulation-based training, AI-assisted surgical planning, and technologies that may fundamentally change how we think about surgical education and competency assessment.

Prenatal screening has moved from maternal serum markers to cell-free DNA to whole genome sequencing. The technology is outpacing our ability to counsel patients about what the results mean. The ethical questions are becoming harder, not easier.

Preeclampsia prediction, stillbirth risk assessment, preterm birth prevention: in every area, machine learning models trained on large datasets are showing performance that exceeds traditional clinical scoring. The question is no longer whether AI can contribute to obstetric decision-making. The question is whether the profession will adopt it in time to help the patients who need it, or whether institutional inertia will delay adoption for another generation.

And running through all of it, a thread that has defined my career: the ethics of what we do. Informed consent. Patient autonomy. The gap between what guidelines recommend and what evidence supports. The tension between standardization and individualized care. The obligation to tell patients what we know, what we do not know, and what we are uncertain about.

What This Series Will Cover

“The Future of ObGyn” will be a regular series examining specific technologies, innovations, and ideas that I believe will shape the next decade of obstetric and gynecologic practice. Each post will follow the evidence, name the obstacles, and make concrete recommendations.

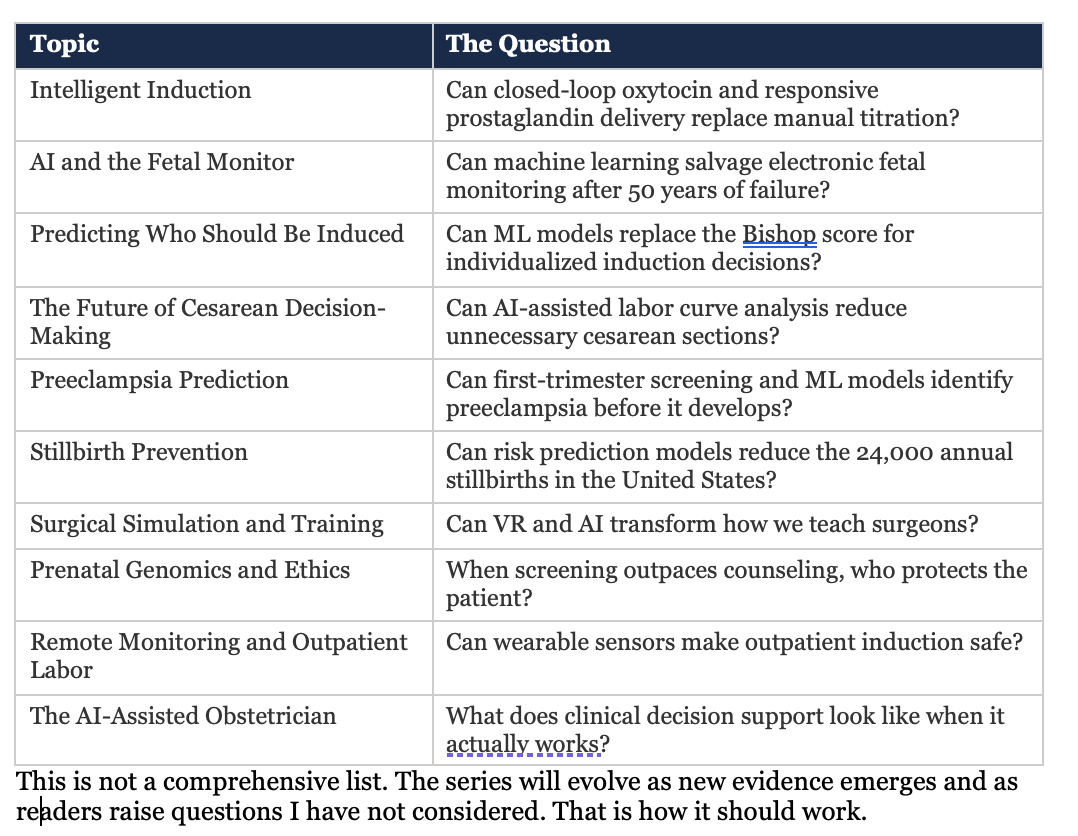

Topics that will be covered may include:

My Rules for This Series

I learned something important from writing the “Routine to Regret” series: every abandoned practice was once promoted by someone who believed in it. Enthusiasm without evidence is how we got DES, routine episiotomy, and continuous EFM. I have no intention of repeating that pattern in the other direction, promoting untested innovations because they sound promising.

These are the rules I will follow:

1. Evidence first. Every claim will be supported by published, peer-reviewed data. When the evidence is strong, I will say so. When it is weak or absent, I will say that too. I will not fabricate references, overstate conclusions, or pretend certainty where none exists.

2. Name the obstacles honestly. Regulatory barriers, market incentives, liability concerns, and clinical conservatism are real. Pretending they do not exist helps no one. But neither does accepting them as permanent. I will distinguish between obstacles that protect patients and obstacles that protect the status quo.

3. Patients come first. Every technology discussed in this series will be evaluated from the perspective of the woman in the bed: does this make her safer? Does it give her better information? Does it respect her autonomy? Technology that serves the institution but not the patient is not progress.

4. Bias must be confronted. AI and algorithmic tools can perpetuate and amplify existing disparities. Every model discussed in this series will be evaluated for bias, equity, and applicability across populations. Innovation that works only for some patients is not good enough.

5. Clinical judgment is not optional. No algorithm replaces the obstetrician, the midwife, or the labor nurse. Decision support means support, not substitution. The clinician sets the goals, interprets the context, and makes the final call. Any technology that cannot operate within that framework does not belong in clinical practice.

Why Now

I am writing this series now because the gap between what is possible and what is practiced has never been wider. The tools exist. The data exist. The computational power exists. What does not exist is the institutional will to move forward.

Obstetrics has a long history of being slow to adopt good ideas and slow to abandon bad ones. That is not a character flaw. It is a structural problem: the combination of regulatory complexity, liability fear, commercial misalignment, and a culture that confuses tradition with evidence. The “Routine to Regret” series documented what happens when that structure prevents us from stopping harmful practices. This series will document what happens when it prevents us from starting beneficial ones.

I have been in this field for more than 50 years. I have seen enough abandoned practices to know what institutional inertia looks like. I have also seen enough genuine progress to know what evidence-based change looks like when it actually happens. The difference is not the technology. It is the willingness to ask uncomfortable questions, follow the data, and act on what we find.

That is what this series intends to do.

🎯 Bottom Line: “From Routine to Regret” asked how obstetrics and gynecology got stuck with harmful practices for decades. “The Future of ObGyn” asks what the profession should be doing now and why it is not. This series will examine AI-driven labor management, fetal monitoring, surgical innovation, predictive analytics, and the ethics of algorithmic medicine, always grounded in evidence, always centered on the patient. The same institutional forces that sustained routine episiotomy for 50 years are now delaying innovations that could save lives. It is time to name them.