The First Obstetric Misdiagnoses: Lessons From Historic Mistakes

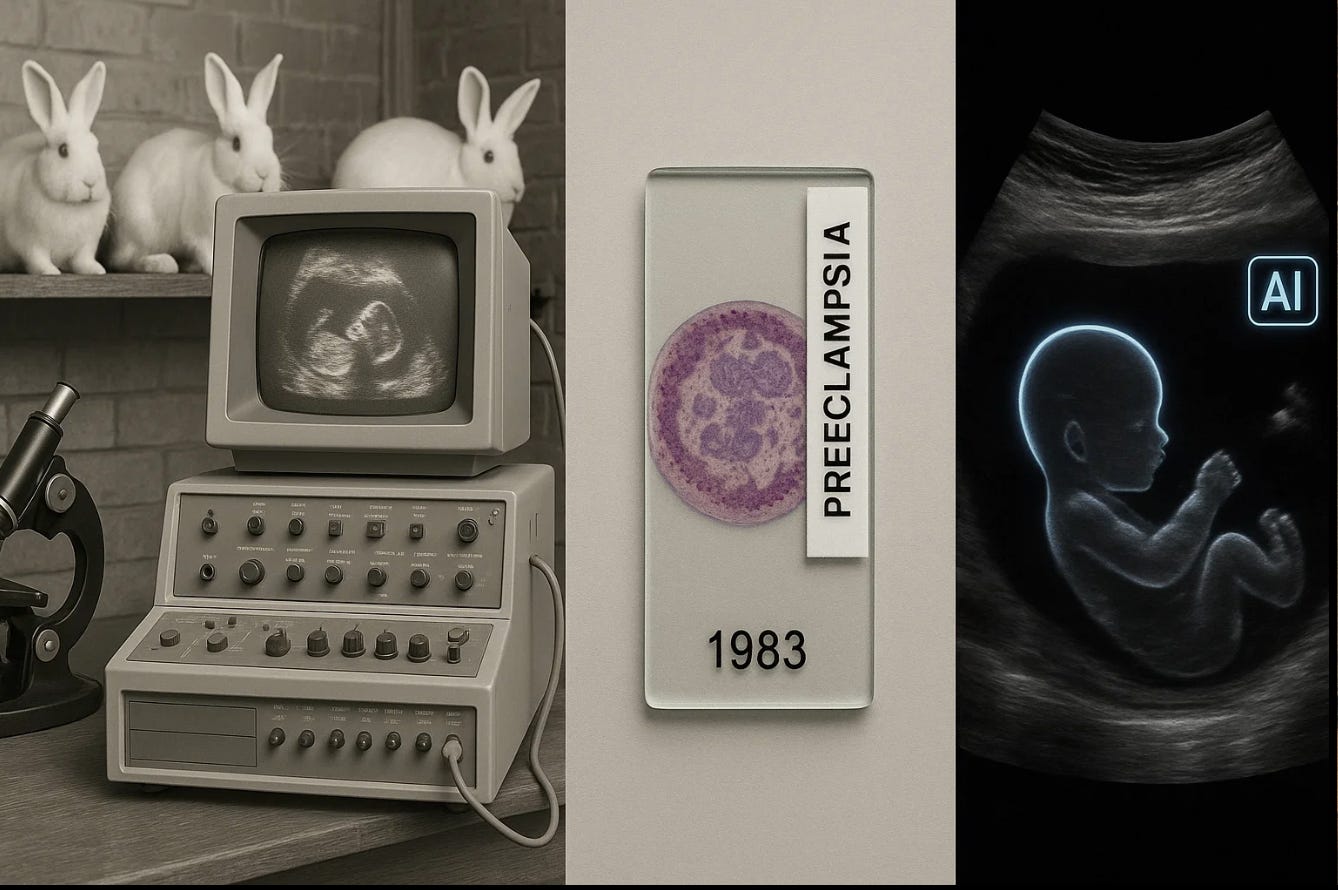

The Obstetric Intellect: From the 1920s rabbit tests to the 1983 “worm” preeclampsia controversy, obstetric history is a chronicle of wrong turns that taught right lessons.

Every scientific breakthrough in obstetrics carries a shadow of error. From pregnancy tests that relied on rabbits, to the first misread ultrasound, to a 1983 paper in AJOG that saw “worms” in women with preeclampsia, our field’s progress has been paved by mistakes that dared to be published. These errors didn’t end progress—they made it possible.

1. When the Rabbit Lied (1920s–1940s)

The first “objective” pregnancy tests, the Aschheim–Zondek test (1928) and Friedman test (1931), injected women’s urine into immature female rabbits or mice. If the animals’ ovaries enlarged, the result was “positive.”

But the tests produced many false positives—tumors or other conditions that secreted similar hormones—and false negatives in very early pregnancies【Aschheim S, Zondek B. Klin Wochenschr. 1928;7:1401–1402】.

By the 1960s, immunoassays replaced animal bioassays, culminating in the first home pregnancy test approved by the FDA in 1976. The errors of the rabbit era gave birth to modern biochemical precision.

Lesson: Even measurable data can deceive when biology is misunderstood.

2. The First Ultrasound Misdiagnosis (Late 1950s–1960s)

When Dr. Ian Donald published his landmark 1958 Lancet paper on ultrasound imaging of abdominal masses and pregnancy【Donald I, MacVicar J, Brown TG. Lancet. 1958;271(7032):1188–1195】, obstetrics entered a new era. But it also entered an age of false clarity.

Early scanners produced grainy echoes easily mistaken for fetal structures. One of the earliest documented ultrasound misdiagnoses—described in the 1960s—was a uterine fibroid misinterpreted as a gestational sac.

The fallout spurred better protocols: correlation with β-hCG values, repeat scans, and strict imaging planes. These are now standard in ACOG’s sonography guidelines.

Lesson: A picture is not a proof—it is an interpretation.

3. “Observation of an Organism Found in Patients with Preeclampsia” (AJOG, 1983)

In 1983, The American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology published a paper titled “Observation of an organism found in patients with preeclampsia”【AJOG. 1983;146(3):311–320】.

Researchers described worm-like structures (1–1.5 mm long) in tissue samples from women with preeclampsia and proposed that a previously unrecognized microorganism—or possibly a parasite—might be involved.

But follow-up studies using electron microscopy and improved tissue preservation failed to confirm the finding. Later re-analyses concluded that the supposed “organisms” were artifacts of tissue fixation, possibly fibrin strands or necrotic villous material.

No subsequent peer-reviewed work has reproduced those findings in the four decades since, and modern pathology attributes preeclampsia to placental ischemia, endothelial dysfunction, and immune maladaptation, not infection.

Lesson: Even peer-reviewed journals can publish observational artifacts. The courage to question one’s own discovery is as important as the courage to make it.

4. The “Molar Pregnancy” Misdiagnoses (1950s–1970s)

Before reliable imaging, clinicians often diagnosed hydatidiform mole based solely on uterine size and high hCG levels. Some women underwent uterine evacuation for presumed molar pregnancy—only to discover later that the pregnancy had been normal or multiple.

The introduction of ultrasound clarified the diagnosis, showing that elevated hCG can occur in normal twins or misdated pregnancies.

Lesson: Acting on incomplete evidence can turn a diagnostic error into irreversible harm.

5. The Rhesus Revolution (1940–1968)

In the 1940s, hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN) was poorly understood. Some believed Rh-negative mothers were “allergic” to their babies. Misdiagnoses led to extreme recommendations—including sterilization—to “protect” mothers from future pregnancies.

It took two decades of immunohematologic research before the mechanism was clarified and the Rho(D) immune globulin prophylaxis introduced in 1968, preventing almost all Rh-related fetal deaths.

Lesson: Misdiagnosis at the level of mechanism can do as much harm as misdiagnosis at the bedside.

6. The Vanishing Twin (1970s–1980s)

With improved early ultrasound came confusion: two sacs one week, one fetus the next. Initially interpreted as “missed abortion of twins,” this phenomenon was later recognized as the vanishing twin syndrome, a common early loss in multiple conceptions【Landy HJ, et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67(3):339–342】.

Lesson: Greater visibility does not always mean greater understanding.

7. The “Blighted Ovum” Trap (1980s–Present)

Modern misdiagnosis persists. Declaring an early gestation “nonviable” based on a single ultrasound—without allowing for variation in ovulation or implantation—can terminate desired pregnancies that might have continued.

Studies show that even with today’s imaging, early scans before 6 weeks carry false-negative rates up to 12–15% for embryonic cardiac activity【Doubilet PM, Benson CB. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1443–1451】.

Lesson: Technology must bend to biology, not the other way around.

8. The “Toxemia of Pregnancy” Era (Before 1950)

Before vascular and immunologic insights, preeclampsia and eclampsia were attributed to “toxins retained during gestation.” Treatments included purgatives and bloodletting. It took mid-century pathology to reveal the real culprit: placental vascular dysfunction and endothelial injury, not systemic “toxins.”

Lesson: Naming a disease wrongly traps generations in false solutions.

The Pattern Beneath the Errors

Across a century of obstetric misdiagnoses, the common thread isn’t necessarily incompetence—it’s confidence. Each discovery was driven by belief that the evidence was sufficient. Whether seeing a fetus where none existed or a worm where only fibrin lay, the error was not in seeing but in believing too soon.

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman might call it the illusion of validity: our tendency to trust patterns that confirm our expectations. Medicine rewards confidence but progress depends on humility.

Reflection / Closing

From the rabbit bioassays of the 1920s to the 1983 “worm” report in AJOG, obstetrics has always advanced by confronting its own illusions. Each generation of clinicians believed it had finally seen clearly into the mystery of pregnancy—only to discover that what it saw was partly a reflection of itself.

The deeper lesson is not about technology but about thinking. We are wired to trust what feels coherent, to prefer a neat story over a complicated truth. When a test result fits our expectations, we stop questioning. When a scan looks convincing, we stop looking. That is how confident minds make confident mistakes.

Progress, in science as in economics, rarely comes from certainty. It comes from friction—the collision between what we think we know and what reality stubbornly shows us. The best systems are not those that prevent error, but those that notice it quickly and learn fast.

The next era of obstetrics will tempt us again with clarity: high-resolution imaging, predictive algorithms, risk scores that claim to know the future. But genuine intelligence, human or artificial, is not about prediction—it’s about doubt. The hardest thing in medicine is not to see more, but to know when we might be wrong.

That, in the end, is how truth is built in obstetrics: not from unbroken confidence, but from a continuous willingness to be proven mistaken, and to start again.

The greatest lesson from these historic mistakes isn’t about technology at all. It’s that truth in obstetrics is iterative, never final. Medicine advances not by eliminating error, but by learning, transparently and publicly, from every one.