The Evidence Room: The Mirage of the “Latent Labor” Curve

Why definitions matter more than data when re-drawing obstetrics.

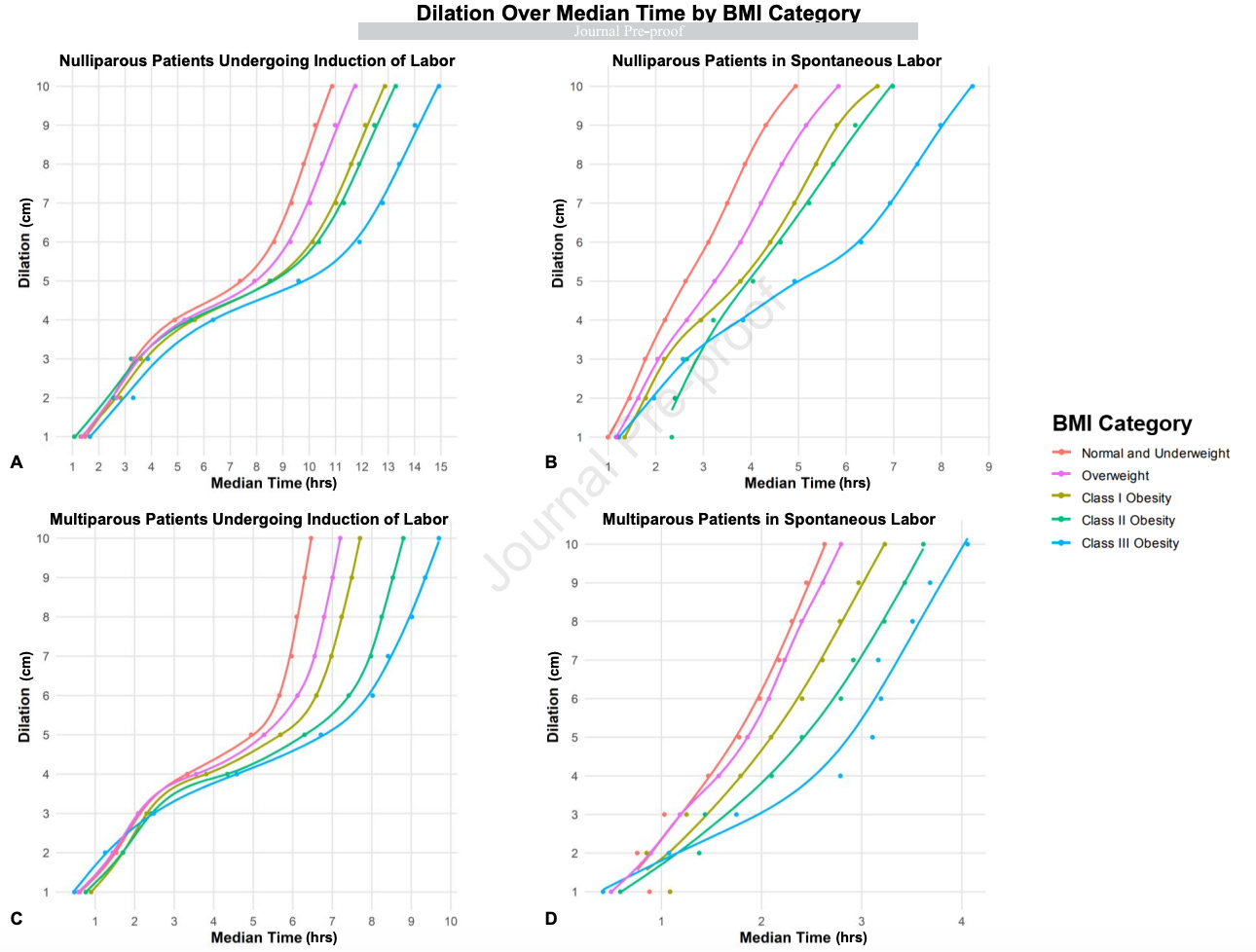

The new AJOG study by Edwards et al. claims that higher maternal BMI is associated with longer labor, driven primarily by extended “latent labor.”

Yet the paper never defines what “latent labor” actually is. That omission is not trivial. It undermines the study’s interpretability and renders its main conclusion, namely that BMI-specific labor curves might reduce unnecessary cesareans, conceptually unsound.

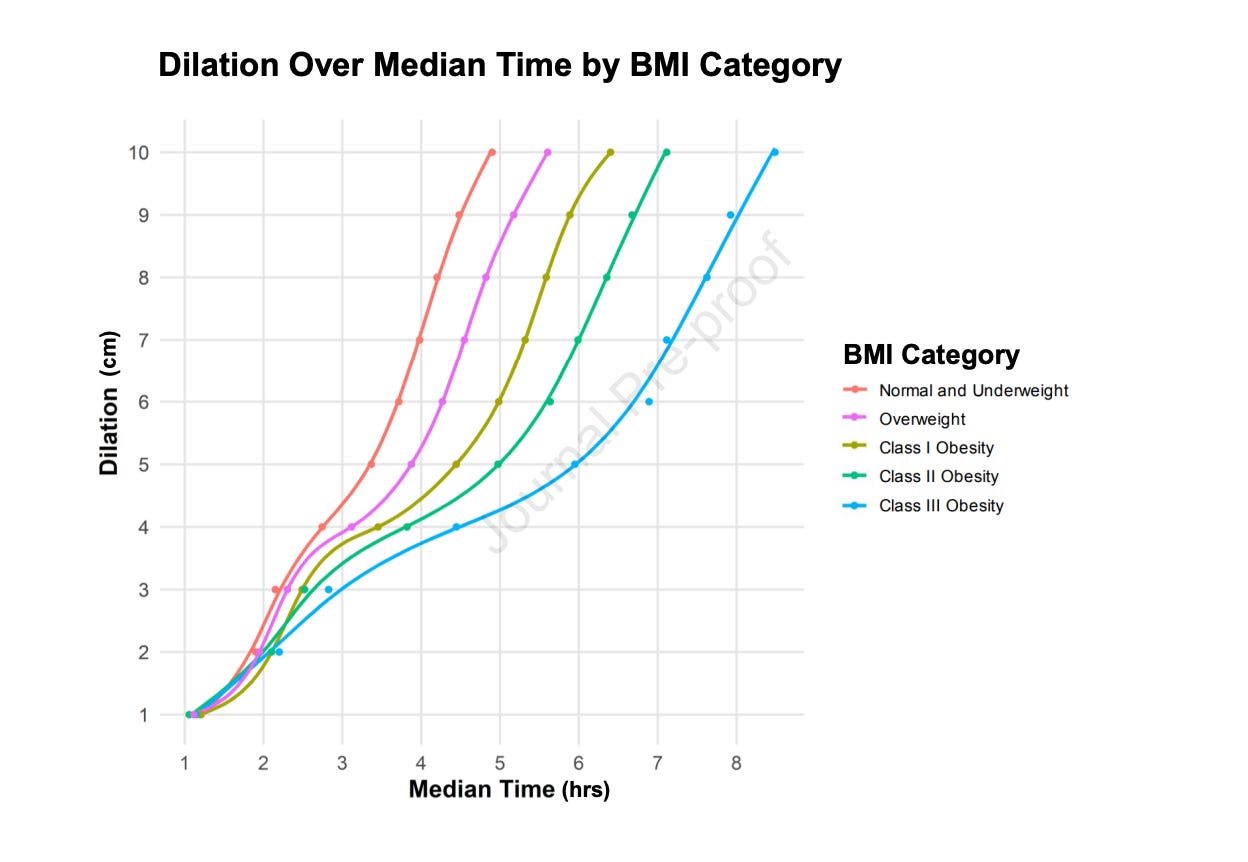

Here is the graph shown in the study, in the latent phase:

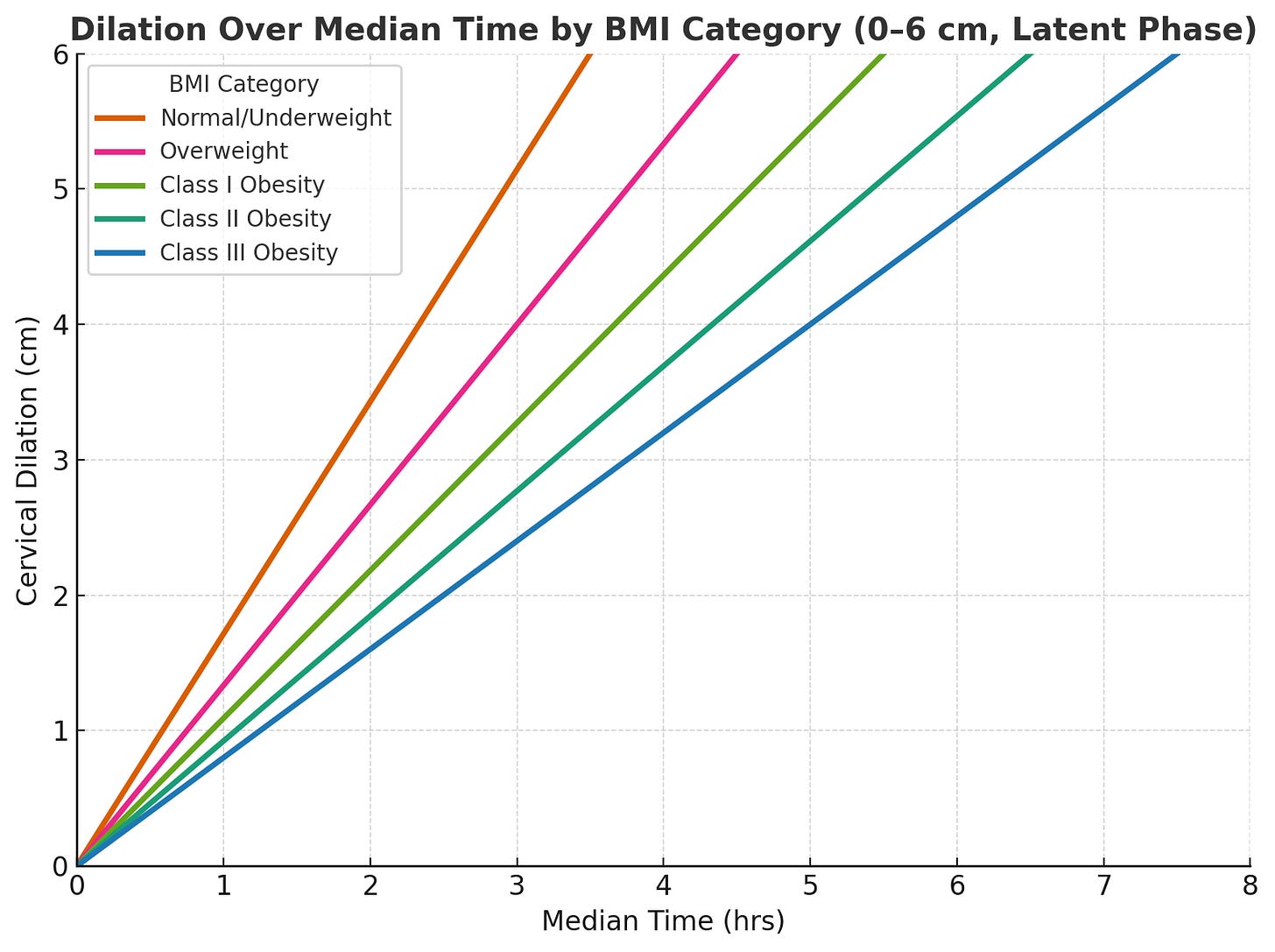

Here is the graph restricted to the latent phase (0–6 cm), beginning at 0 hours. It shows that as BMI increases, the slope flattens, indicating progressively slower cervical dilation before the active phase of labor begins.

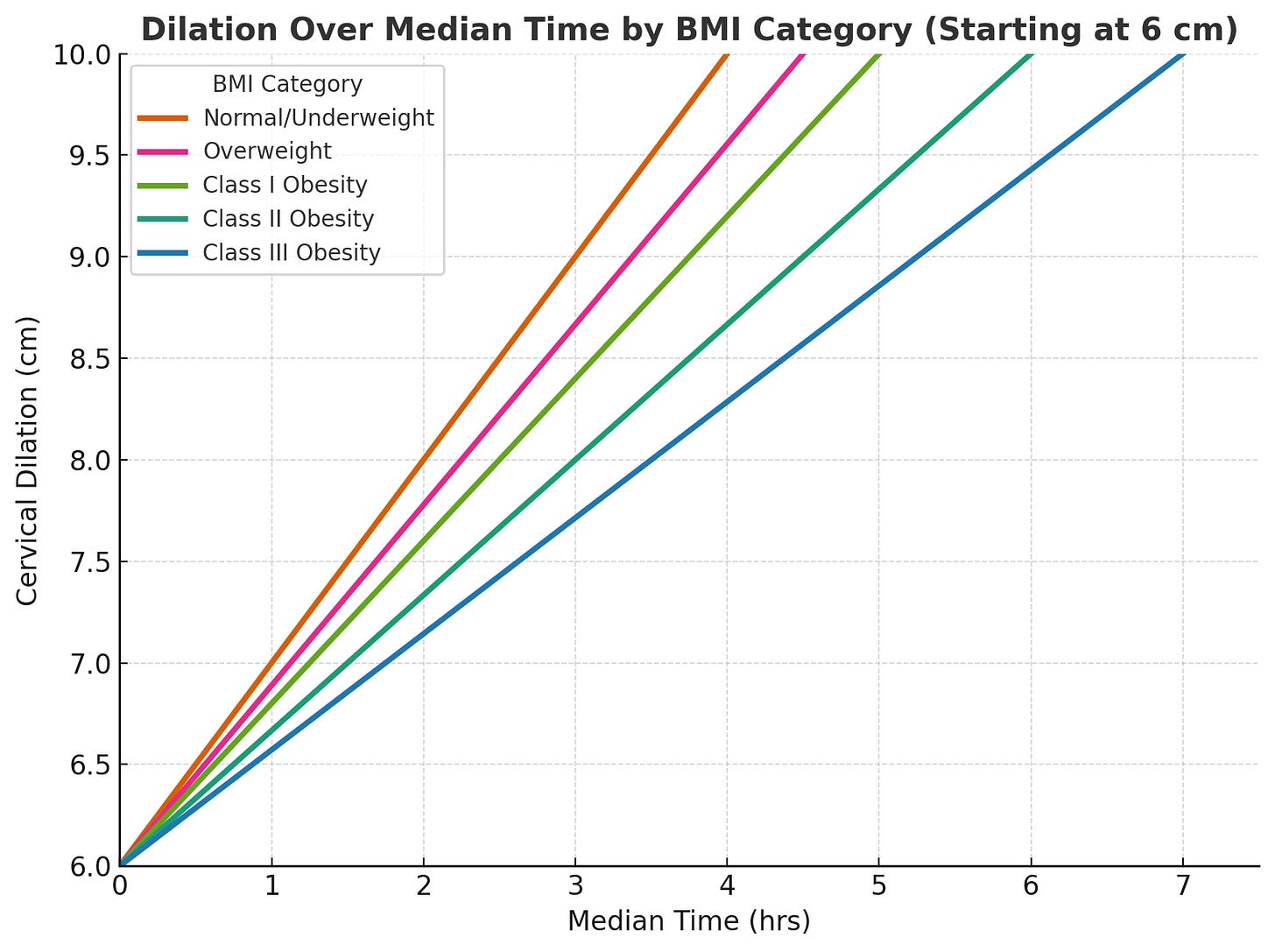

And here is the graph of the actual active PHASE of labor from 6 cm on:

Here is the redrawn graph showing cervical dilation from 6 to 10 cm, starting at 0 hours for all BMI groups. It isolates the active phase of labor, emphasizing that BMI-related differences in dilation time appear mainly before 6 cm rather than during the active phase.

For the active phase (D≥6 cmD \ge 6\,\text{cm}D≥6cm), cervical dilation followed an approximately linear function: Di(t)=6+ritD_i(t) = 6 + r_i tDi(t)=6+rit where Di(t)D_i(t)Di(t) is dilation (cm) over time ttt (hours) for BMI class iii. Empirically, rir_iri values were similar across BMI groups:

rNW≈rOW≈rO1≈rO2≈rO3≈1.0 cm/h.r_{NW} \approx r_{OW} \approx r_{O1} \approx r_{O2} \approx r_{O3} \approx 1.0\,\text{cm/h.}rNW≈rOW≈rO1≈rO2≈rO3≈1.0cm/h.

Therefore, for D≥6 cmD \ge 6\,\text{cm}D≥6cm,

dDdt≈1.0 cm/h\frac{dD}{dt} \approx 1.0\,\text{cm/h}dtdD≈1.0cm/h

and

dDdt was independent of BMI,\frac{dD}{dt}\ \text{was independent of BMI,}dtdDwas independent of BMI,

indicating no significant BMI-related difference in active-phase labor progression

What it means

In obstetrics, the latent PHASE of labor refers to the period of gradual cervical change before the onset of the active phase, when regular contractions accelerate dilation and descent. The distinction was first formalized by Friedman in 1954 and remains foundational: a labor CURVE properly begins with the active phase, not the pre-active latent period, whose onset and duration are highly variable and poorly measurable.

Contemporary frameworks, including ACOG’s 2024 First and Second Stage Labor Management guideline, reaffirm that abnormal labor progress should not be diagnosed until at least 6 cm dilation, explicitly recognizing that early cervical change does not follow a predictable curve.

By defining “latent labor” as 0–6 cm and plotting it as part of a continuous dilation-time function, the authors collapse two physiologically distinct processes into one analytic unit. This conflation violates the logic of the labor curve itself. The so-called “latent phase” before 6 cm may involve inconsistent documentation intervals, frequent extrapolation of missing data, and variable clinical thresholds for admission.

Edwards et al. acknowledge using extrapolated cervical values between exams to fill temporal gaps—an approach that, while statistically convenient, introduces artifacts where no true observation existed. The consequence is a smoothed illusion of labor progress during a phase that was neither consistently observed nor uniformly defined.

Furthermore, all participants in the cohort achieved vaginal delivery.

Excluding cesarean births eliminates precisely the population in which “slow progress” prompts intervention. The resulting curves thus describe only successful outcomes, not physiologic norms.

Any assertion that BMI-specific curves could prevent unnecessary cesareans rests on circular reasoning: the study omits all cesareans, then infers that prolonged latent phases among vaginal deliveries justify more patience in others.

The reported finding. that active-phase duration did not differ significantly by BMI, is clinically the most credible and consistent with prior evidence. In contrast, the “latent labor” effect may simply reflect differences in timing of hospital admission, induction protocols, or documentation density rather than intrinsic myometrial differences. Although the authors speculate about oxytocin responsiveness and contractility, no physiologic data were collected to support that inference.

Another conceptual inconsistency lies in terminology. The paper repeatedly refers to “latent labor,” yet standard obstetric nomenclature uses “latent PHASE of labor.”

The difference is not semantic. “Labor” denotes the total process from onset of regular contractions to delivery, while “phase” delineates a specific segment within that process. Precision in language reflects precision in physiology—and, by extension, in data interpretation. When the definitional foundation shifts, so does every conclusion built upon it.

Methodologically, the study’s strengths are clear: a large sample (over 41,000 vaginal births), rigorous statistical modeling, and stratified analyses by parity and induction status.

Yet these strengths cannot compensate for the categorical uncertainty at its core. If “latent phase” is misapplied, the claim that BMI prolongs it becomes untestable. No statistical adjustment can rescue a construct that lacks diagnostic clarity.

Clinically, obstetricians should remain cautious before adopting BMI-based labor curves. The data suggest that heavier women may experience longer early labor before active acceleration, but there is no evidence that this represents pathologic dystocia or that altering intervention thresholds improves outcomes.

Until “latent labor” is precisely defined and prospectively measured, new curves risk codifying error rather than refining practice.

In essence, this study raises the right question but frames it on the wrong axis. The problem is not that BMI-specific curves are unwarranted—it is that the underlying physiologic construct was mislabeled and incompletely observed. Before redrawing labor curves, obstetrics must first redraw its definitions.