The Economics of Emotional Survival: Three Perspectives on Burnout and Hostility in Medicine

Why Building a Bigger Life Isn't Optional: Lessons from a Forced Medical Leave

I became an ObGyn to bring life into the world and teach others to do the same. Then at 46, my body forced me to stop. A major medical event—one I still don’t discuss casually—took me out of clinical practice for several years. I lost part of my voice and my balance. I fought it at first, convinced I was nothing without my white coat. But medicine didn’t wait for me. My patients went elsewhere. Life continued.

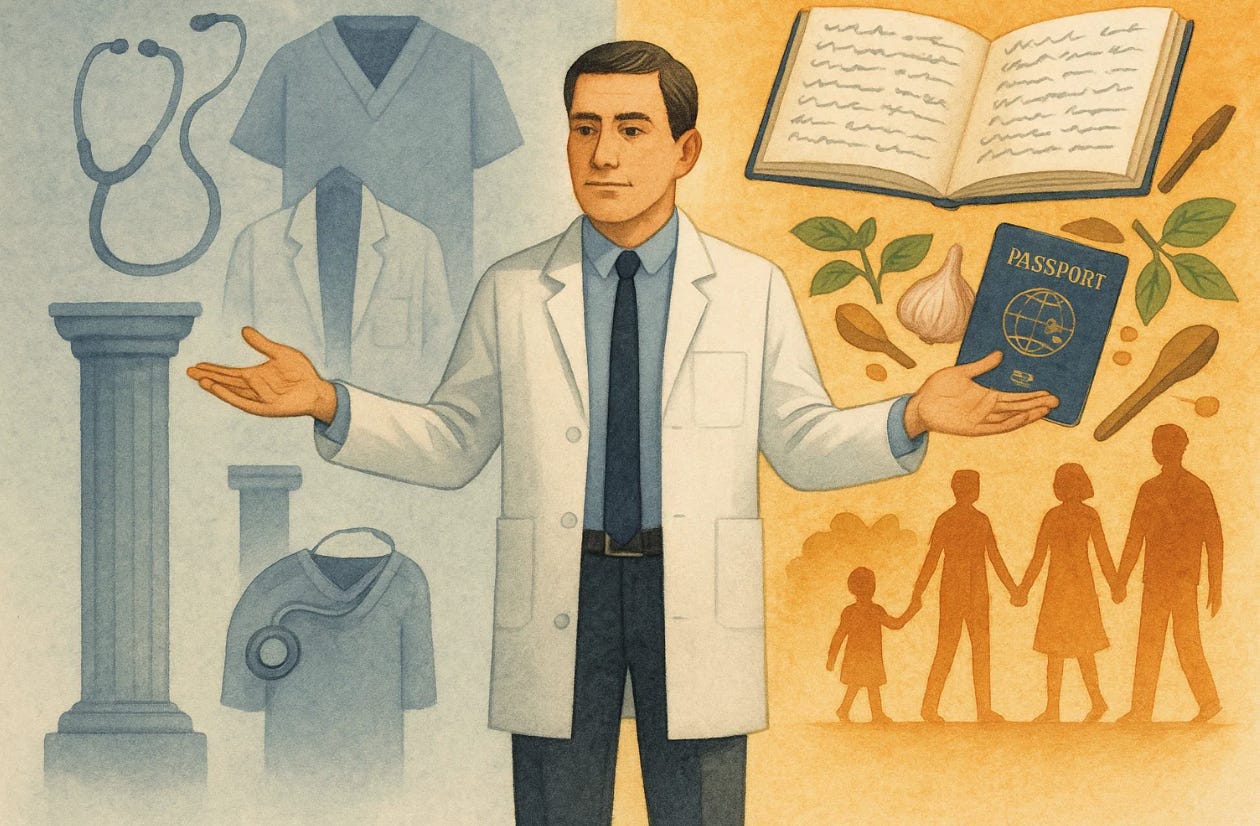

During those years away, something unexpected happened: I discovered I was still a person. I started writing—not just academic papers, but essays and fiction that had nothing to do with obstetrics. I published under my own name and sometimes under pseudonyms, exploring ideas that had been dormant for decades. I traveled, really traveled, not just attending conferences. I became obsessed with mastering recipes that had intimidated me. I was fully present with my family in ways I hadn’t been since residency. I started creating a website that became the most successful ObGyn website in the world.

When I finally returned to medicine, I was different. Now when a patient screamed at me despite my best efforts, or leave a vicious review after a successful surgery, it still hurts—I’m human. Or when colleagues criticized me for insisting creating systems so patients have the safest possible care. But it disn’t threaten my entire identity anymore. Because I learned the hard way that medicine can be taken from you at any moment, and you need to be someone without it.

Through Paul Krugman’s Lens:

Paul Krugman, Nobel laureate in economics and longtime columnist, built his career analyzing market failures, systemic risks, and perverse incentives in complex systems. If he were to examine physician burnout, he’d recognize it immediately as an economic problem masquerading as a personal one.

He would say: My colleague’s forced medical leave represents what economists call an “exogenous shock”—an external force that disrupts the entire system. In this case, it revealed a dangerous over-concentration of identity capital in a single asset class. He had built his entire portfolio around one investment: physician identity. When that investment became temporarily worthless through no fault of his own, he faced total bankruptcy of self-worth.

This is the hidden systemic risk in medicine. We train physicians to invest everything—time, energy, identity, self-worth—into their medical careers. This creates enormous vulnerability to market crashes, whether from health crises, malpractice suits, licensing issues, or simply the cumulative toll of hostile patient interactions. The system has no built-in diversification strategy.

Consider the opportunity cost calculation differently. When my colleague was forced out at 46, he inadvertently conducted a natural experiment in identity diversification. Those years away weren’t lost—they were an unplanned investment in alternative identity portfolios: creating websites, writer, traveler, chef. When he returned to medicine, he had a balanced portfolio. A hostile patient interaction now represents a 20% drop in one holding, not a total market collapse.

The perverse incentive structure in medicine actually punishes this kind of healthy diversification. The system rewards physicians who sacrifice everything for medicine—who skip their kids’ recitals, who haven’t taken real vacation in years, who have no identity outside the hospital. But this creates catastrophic fragility. One lawsuit, one health crisis, one licensing issue, and they have nothing.

Through Daniel Kahneman’s Lens:

Daniel Kahneman, the psychologist who won the Nobel Prize in Economics for his work on human judgment and decision-making, spent his career documenting how systematically irrational we are. His distinction between System 1 (fast, emotional, automatic) and System 2 (slow, deliberate, rational) thinking explains why intelligent physicians can be devastated by single hostile encounters despite years of positive ones.

What my colleague experienced is what psychologists call “forced decentering”—an involuntary disruption of automatic thought patterns. For decades, System 1 thinking had operated on a simple equation: physician identity = total self-worth. When illness removed physician identity, the equation should have resulted in zero self-worth. Instead, something fascinating happened.

During forced absence from medicine, he developed what we call “self-complexity”—multiple, independent self-schemas. Website developer. Writer. Traveler. Cook. Parent. Teacher. These weren’t hobbies or stress relief; they became genuine competence domains with their own feedback loops and sources of self-efficacy. Research shows this multiplicity is one of the strongest predictors of resilience to setbacks.

Here’s the cognitive insight: When a hostile patient triggers the amygdala now, System 1 tries to run its old catastrophic script—”This patient’s anger means I’m a failure.” But now System 2 has actual counter-evidence from multiple domains. “I published an essay last month that resonated with thousands. I perfected a complex recipe yesterday. I planned an amazing family trip. I am competent and valued in multiple arenas. This patient’s anger is one data point, not the entire dataset.”

This is what psychologists call “cognitive reappraisal,” but it only works if you have genuine alternative domains to draw from. You can’t fake self-complexity. Those years away from medicine weren’t wasted—they were an unplanned but invaluable investment in psychological infrastructure.

The affect heuristic—using emotional responses as proxies for evaluating complex situations—works in both directions. When you feel competent and appreciated in multiple life domains, individual failures don’t trigger existential crises. The availability heuristic also shifts: recent positive experiences in other domains are more cognitively “available” to counterbalance negative patient interactions.

Synthesis:

I didn’t choose to learn this lesson. At 46, I was forced to stop working for several years due to a medical crisis. I thought I’d lose everything because I thought medicine was everything. Instead, I discovered that the forced diversification saved me.

Now when someone asks how to handle hostile patients and prevent burnout, I don’t offer platitudes about resilience. I tell them what I learned when medicine was taken from me: You need to be someone else. Not eventually. Now. Not as a hobby, but as a genuine alternative identity.

Since returning to practice, and rstecially since part-time retirement, I write and publish regularly. I plan elaborate trips. I’ve become genuinely skilled at cooking. I’m present with my family in ways I wasn’t before my illness forced me to be. These aren’t rewards for surviving difficult clinic days—they’re the infrastructure that makes surviving possible.

When someone directs their anger at me now, it still hurts. But it doesn’t make me want to quit anymore, because I know I’m not just a doctor. My illness taught me that at great cost.

You don’t have to wait for a crisis to learn the same lesson. Build a bigger life now, while you can. Not someday—today. Because medicine can be taken from you at any moment, through illness, injury, or just the accumulated weight of too many hostile interactions. And you need to still be someone when it is.

Thank you for reminding us that being a physician is only one aspect of our value and humanity.

I also was trained as an ObGyn and underwent a horrible case with a subsequent lawsuit and practice fight that made me consider suicide. I went on to join another practice, and regained my confidence slowly, eventually becoming chair of the department. Then I was forced by medical necessity to retire at 65, when I was doing 4 jobs and trying to balance life. Cancer gave me the excuse I needed or the release I needed to back away from clinical practice and take care of myself. I returned to work part time as an educator at a private medical school and continue that at 72. However, I also have time for music festivals, travel, cooking gourmet meals, and regular exercise. I am also enjoying my two year old grandson. Our children are very fortunate that my husband was able to stay at home with them for 18 years while I worked too much! I wish I had had more time with them but that ship has sailed, and my husband is still keeping us all together.

We will celebrate our 50th wedding anniversary next month! I hope that our future physicians will be able to have a healthy life in ways that we did not in private practice!