The Due Date: The Most Important Number in Pregnancy

The Obstetric Intellect: In 1812, Franz Karl Naegele, a professor of obstetrics at Heidelberg, proposed a simple method to estimate when a baby would be born.

Every pregnancy revolves around a single date—the due date.

It dictates when ultrasounds are done, when screenings are interpreted, when labor is “post-term,” and when an induction is “elective.”

Here are other important aspects of pregnancy that revolve around a single date — the due date (EDD):

Timing of Ultrasound Scans – The gestational age determines when key ultrasounds are scheduled, such as the first-trimester dating scan, nuchal translucency screen, and anatomy survey.

Interpretation of Screening Tests – Blood tests for genetic or structural anomalies (like AFP, quad screen, or cfDNA) are valid only within specific gestational windows based on the due date.

Determination of Fetal Growth Percentiles – Ultrasound growth charts and Doppler interpretations depend on the correct gestational age anchored to the due date.

Assessment of Fetal Viability and Preterm Birth – The classification of “previable,” “preterm,” and “term” depends entirely on gestational age relative to the EDD.

Definition of “Post-term” and “Late-term” Pregnancy – Management decisions after 41–42 weeks hinge on whether the EDD was calculated accurately.

Timing of Induction of Labor – Whether an induction is considered elective, medically indicated, or post-term is defined by the gestational age count from the due date.

Timing of Antenatal Corticosteroids and Magnesium Sulfate – Administration for fetal lung maturity or neuroprotection must occur within precise gestational windows (e.g., 24–34 weeks).

Administration of Rho(D) Immune Globulin – Typically given at 28 weeks and again postpartum, both based on the gestational timeline.

Diagnosis of Growth Restriction or Macrosomia – Ultrasound biometry compared to gestational norms determines whether a fetus is too small or too large for dates.

Eligibility for Specific Interventions or Procedures – Cerclage removal, trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC), and timing of planned cesarean deliveries all depend on gestational age.

Interpretation of Fetal Testing Results – Nonstress tests, biophysical profiles, and Doppler findings are judged relative to gestational expectations, not absolute values.

Legal and Ethical Definitions – The due date influences definitions of fetal viability, abortion limits, parental leave timing, and even neonatal resuscitation guidelines.

Yet this cornerstone of prenatal care traces back to a German obstetrician doing calendar math over 200 years ago, long before anyone knew when ovulation or fertilization actually occurred.

The Birth of a Formula: Naegele’s 1812 Rule

In 1812, Franz Karl Naegele, a professor of obstetrics at Heidelberg, proposed a simple method to estimate when a baby would be born. He advised adding one year, subtracting three months, and then adding seven days to the first day of the last menstrual period.

That was it.

No reference to ovulation. No “40 weeks.” No 280 days. Just an arithmetic trick to move across the months of the calendar.

Naegele’s method worked reasonably well, given what was known at the time. The physiology of ovulation and conception was still a mystery—Karl Ernst von Baer wouldn’t discover the mammalian ovum until 1827—so Naegele used what every woman could report reliably: her last period.

From Calendar to Counting: The 280-Day Rule

Decades later, physicians began turning Naegele’s calendar operation into a fixed duration. By the mid-1800s, English and American textbooks had started describing pregnancy as lasting “ten lunar months or 280 days.”

Charles D. Meigs wrote in The Philadelphia Practice of Midwifery (1838) that “the common duration of pregnancy is two hundred and eighty days or forty weeks.”

Fleetwood Churchill, in Dublin, echoed the same numbers in the 1840s.

By the late 19th century, Karl Schroeder’s Lehrbuch der Geburtshülfe (1877) explicitly linked the two concepts: “280 Tagen … drei Monate abzieht … sieben Tage dazu addirt.”

The rule had finally been expressed both ways—calendar and numeric—and soon became the standard phrasing in English-language obstetrics.

When Williams Obstetrics appeared in 1903, it confidently stated that pregnancy lasts “about 280 days from the first day of the last period.”

By then, Naegele’s mental arithmetic had become an international doctrine.

Biology Catches Up: The 266-Day Reality

Once scientists understood ovulation, the math changed again.

By the late 19th century, embryologists recognized that fertilization happens about two weeks after the start of the last period. In the early 1900s, Franklin Mall and Wilhelm His, studying dated embryos, established that the biological gestational length was about 266 days from conception, not 280 from the LMP.

That distinction persists today.

Clinicians still date pregnancies from the last period (because that’s when the clock starts on the calendar), but embryologists measure from fertilization, which is biologically more precise.

So, every “40-week” pregnancy is really about 38 weeks post-fertilization.

We’ve known this for over a century—but the simplicity of “40 weeks from the LMP” has proven irresistible.

When Dr.AI Meets Dr. Naegele: Can Algorithms Predict Birth Better Than We Can? A Modern Re-examination: 77,767 Days of Data

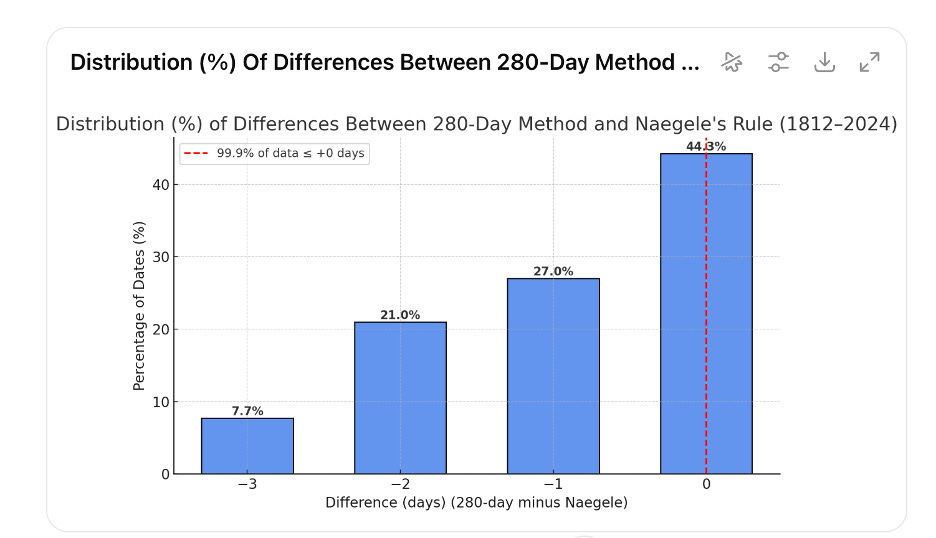

Using real data to explore whether machine learning can outperform two centuries of obstetric convention—and what that means for trust in both humans and machines.To see just how Naegele’s arithmetic compares to the 280-day convention, I recently revisited his rule with a modern twist. Using generative AI to automate the calculation, we compared both methods for every calendar day from January 1, 1812, through December 31, 2024—a span of 77,767 days.

For each day, the difference between the two estimated due dates was calculated as:

(280-day date) − (Naegele’s date).

The result?

The two are similar—but not identical.

DifferenceNumber of CasesPercent−3 days6,0167.7%−2 days16,32621.0%−1 day21,00827.0%0 days34,44844.3%Total77,767100%

In every single case, the 280-day rule predicted a slightly earlier due date than Naegele’s original formula. The gap ranged from zero to three days, entirely because of month length and leap-year differences—not biology.

In other words, Naegele’s 1812 calendar arithmetic and the modern “280-day” rule are not perfectly equivalent, even though they have been treated as such for over a century.

Why It Still Matters

At first glance, a two- or three-day difference might seem trivial. But in obstetrics, precision matters.

A 3-day shift can change how a prenatal screen is interpreted, whether a fetus is labeled “growth-restricted,” or when a patient crosses into “post-term.”

Entire treatment algorithms depend on gestational age.

Ultrasound dating has improved accuracy dramatically, especially when performed early in the first trimester. Yet the LMP-based estimate remains the foundation for every chart, every lab interpretation, and every policy defining “term” pregnancy.

Naegele’s 200-year-old arithmetic still determines how modern medicine defines the timing of birth.

The Lesson of a Calendar

The persistence of Naegele’s rule is a lesson in how medicine turns convenience into doctrine.

It began as a workaround for missing biological knowledge, evolved into a numeric shorthand for bureaucratic record-keeping, and became codified by habit.

Even after we learned more precise biological truths, the original calendar persisted because it was simple, universal, and—most importantly—good enough.

That combination is powerful.

It’s how many clinical “rules” endure long past their scientific expiration date.

What We Should Teach Today

I went to AI/Gemini and asked about the best way to calculate the due date. They gave the wrong answer. Here is what it responded:

The most common method for calculating a pregnancy due date based on the last menstrual period (LMP) is Naegele’s Rule. This rule provides a simple calculation for an estimated due date (EDD), but it’s important to remember that it is just an estimate. A typical pregnancy lasts about 40 weeks (280 days) from the first day of the last menstrual period.

Every medical student memorizes “add one year, subtract three months, add seven days.”

But few are told that this was invented before ovulation was even discovered.

Or that it isn’t exactly the same as 280 days.

Or that 266 days from fertilization is biologically truer.

In an age of digital charts and AI-driven prediction models, perhaps we should return to teaching the origin of the rule itself—not to discard it, but to understand its limits.

Naegele’s insight remains brilliant in its simplicity, but our technology can now refine what he could only approximate with pen and paper.

Reflection

When a 19th-century obstetrician used a paper calendar to predict when a baby would be born, he set in motion one of medicine’s longest-surviving conventions. Two centuries later, algorithms and ultrasounds still revolve around the same date he tried to calculate by hand.

Medicine, like economics, runs on what Daniel Kahneman called “the illusion of understanding.” We cling to Naegele’s rule the way economists once clung to balanced budgets—because it feels rational, not because it is. The 280-day dogma satisfies our craving for predictability in a field defined by uncertainty. It’s cognitive comfort disguised as clinical precision. As Kahneman might say, it’s a classic System 1 shortcut: fast, familiar, and wrong in just the right way to be useful. And as Paul Krugman would remind us, once a convention becomes institutionalized—on forms, in software, in law—it survives not through truth, but through inertia. The obstetric calendar keeps ticking, even when the science has moved on.

Maybe the enduring lesson isn’t about precision at all.

Maybe it’s that the search for certainty in pregnancy will always begin—and end—with a question that no formula can fully answer: When will this baby arrive?