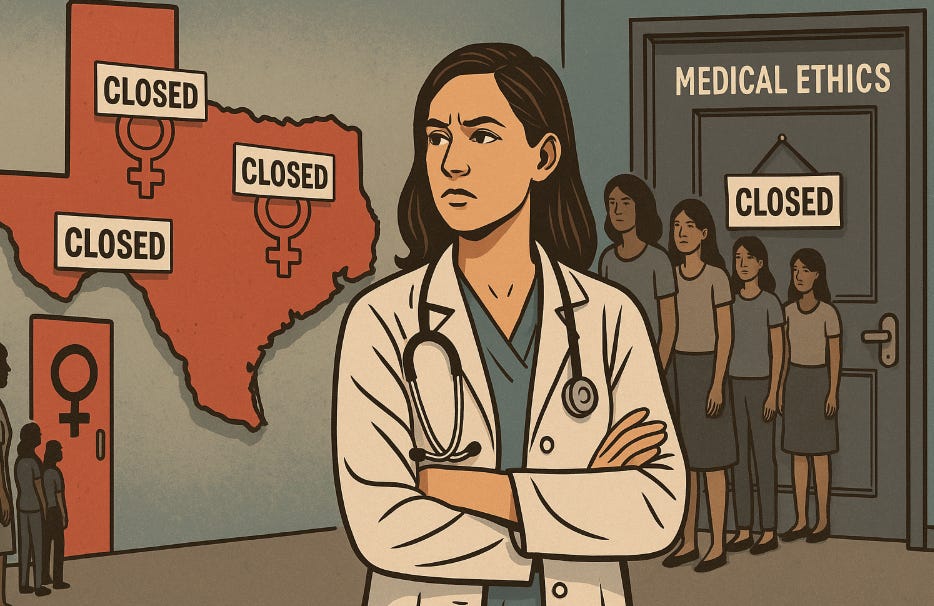

Texas and the Doctor Shortage: An Ethical Crisis for Women and Medicine

Texas laws don’t just harm women as patients—they drive women out of medicine as doctors. The result: deeper shortages, greater risks, and a collapse of trust.

A profession in crisis

Not long ago, I was attending a group of medical students, mostly young women, who talked about their career plans. Several were interested in obstetrics and gynecology. When I asked where they imagined practicing, one said bluntly: “Anywhere but Texas. I won’t work where reproductive freedoms have ben removed and where I cannot practice ethical medicine.” The room fell quiet, but heads nodded. It wasn’t about climate or lifestyle. It was about fear—fear of prosecution, fear of being unable to care for patients, fear of losing their medical license for simply doing what they were trained to do.

Texas, like several other states, has enacted extreme abortion bans with criminal penalties for physicians. These laws do not simply restrict abortion—they undermine women’s health, push patients into danger, and corrode the very practice of medicine.

The growing shortage of doctors

Texas already faces one of the worst physician shortages in the country. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, Texas ranks near the bottom in doctors per capita. Rural areas are hit especially hard, with counties where no ObGyn is available at all. Patients drive hours for prenatal care or even routine screenings. Maternal mortality rates in Texas remain higher than the national average, and the gaps in access only widen the crisis.

This shortage is not just about numbers—it’s about choices. Why would young doctors, especially young women who now make up more than half of medical graduates, choose to build careers in a state that strips them of their own reproductive rights and criminalizes core aspects of their work? Medicine is demanding enough without adding the risk of a prison sentence for saving a patient’s life.

Practicing under fear

Ethical practice in obstetrics and gynecology depends on timely, evidence-based interventions. A woman with a septic uterus, severe preeclampsia, or preterm premature rupture of membranes may need pregnancy termination to survive. In Texas, doctors must hesitate, consult hospital lawyers, or wait until the patient is closer to death—because the law requires proof that death or severe harm is imminent.

This is not patient care. It is political interference in clinical judgment. It forces doctors to weigh not only what is best for their patients but also what will keep them out of jail. Every delay, every hesitation, every forced “wait and see” carries risk—not only for women’s health, but for their lives.

The ethical impossibility of ObGyn practice in Texas

ObGyns in Texas are trapped in a cruel paradox. If they provide care, they risk prosecution. If they withhold care, they violate their oath. Ethics is not an accessory in medicine; it is its foundation. Without it, medicine becomes something else entirely.

Some argue that doctors should “stay and fight from within.” But every patient encounter is a matter of health, dignity, and survival. When a legal system makes responsible practice impossible, staying means colluding with harm. Practicing in Texas today as an ObGyn is not just difficult—it is ethically compromised.

Why young doctors are leaving

Medicine is also a personal choice about where to live, where to raise families, and where to feel safe as a professional and as a woman. For young female doctors, the message from Texas is clear: We will control your body as much as your patients’.

Why would they go? They don’t. They are choosing states where their expertise is valued, their rights are intact, and their patients can receive the care they deserve. Texas, instead of recruiting the next generation of physicians, is actively driving them away.

The ethical dilemma deepens when we consider the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ABOG), whose central organization is located in Dallas, Texas. Every year, hundreds of young ObGyns are required to travel there to sit for their board examinations. But what happens when a candidate is herself pregnant and develops a complication—such as preeclampsia or preterm rupture of membranes—that, under Texas law, cannot be managed according to accepted medical standards? These doctors, at the very moment of proving their competence, may find themselves in a state where their own health and lives could be jeopardized by laws that criminalize appropriate care. This raises an uncomfortable but urgent question: is it ethical for ABOG to continue forcing young physicians into an environment where they cannot be guaranteed safe, evidence-based medical treatment?

The broader lesson

Texas is a warning. Stripping reproductive rights does not just harm women as patients—it drives women out of medicine as physicians. It deepens shortages, raises risks, and leaves communities without care. When evidence-based medicine is criminalized, trust between doctor and patient collapses.

And so the question is not just for Texans. It is for all of us: Do we want a healthcare system where doctors are free to act according to science, ethics, and compassion? Or one where women—both as patients and as physicians—pay the highest price for political control?

Reflection

The exodus of physicians from Texas is more than a workforce crisis. It is an ethical indictment of a system that undermines women’s rights, endangers patients, and corrupts the practice of medicine itself. No incentive program, no recruitment campaign, can fix this. Only restoring trust, rights, and ethical freedom can.

Until then, the shortage will deepen. And women—in the exam room, in the delivery room, and in the medical classroom—will carry the burden.