Tailored Prenatal Care from ACOG. A Promising Redesign at Risk of Becoming Rationed Care

Why ACOG’s vision will succeed only if implementation, accountability, and equity are treated as core clinical obligations, not optional add-ons

According to a document from May 2025, this ACOG Clinical Consensus argues that prenatal care should stop being a fixed 12–14 visit template and become a tailored service plan. The core idea is simple: match visit frequency, monitoring, modality, and social support to a pregnant woman’s medical risk, social risk, and preferences. The document is also candid that this is not “plug and play” because implementation requires resources at the health system, payer, and community levels.

What ACOG is recommending, in plain language

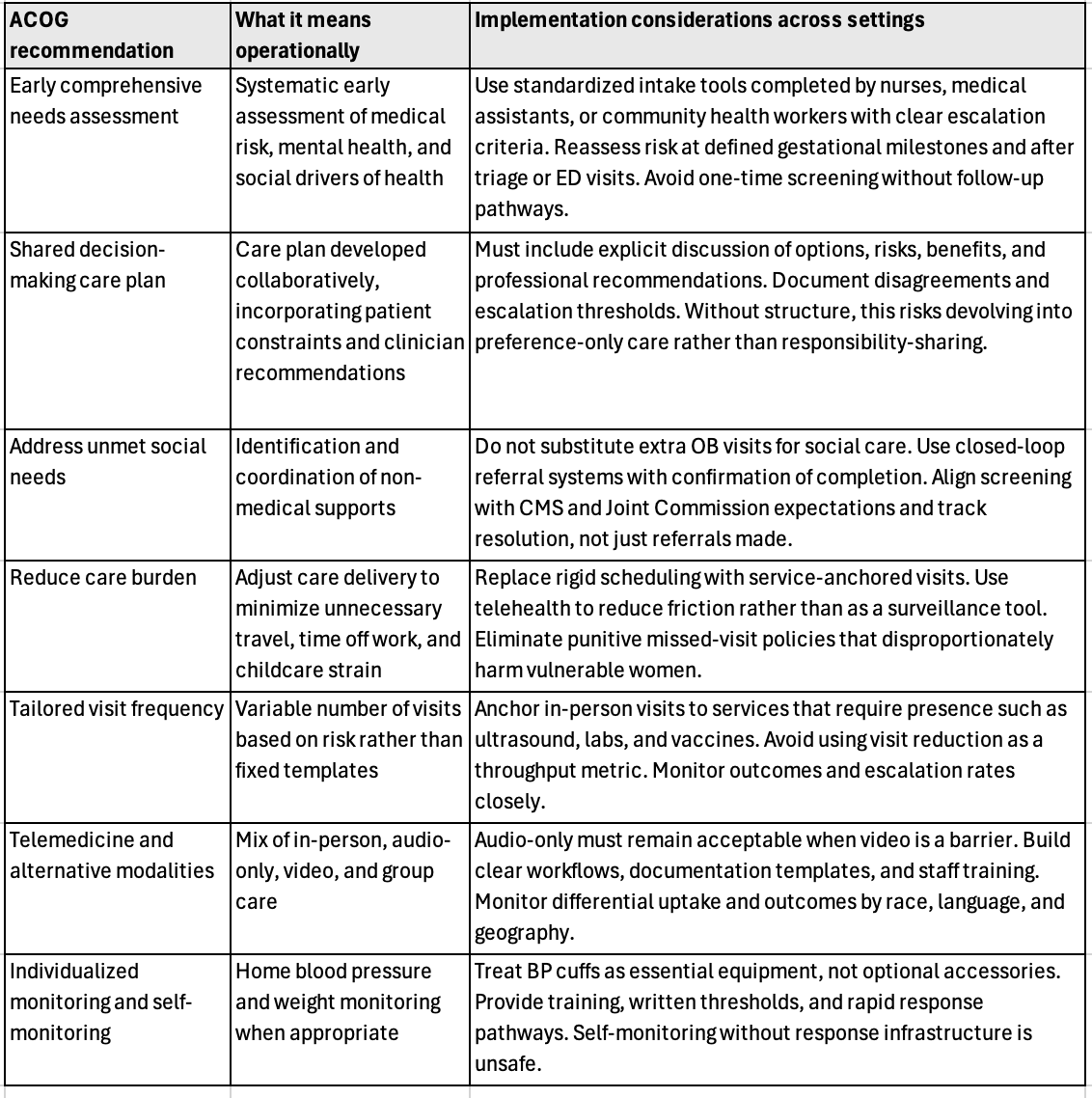

ACOG’s consensus recommendations can be summarized as seven operational moves: (1) early comprehensive needs assessment, (2) shared decision making to build a care plan, (3) identify unmet social needs and coordinate assistance, (4) adjust care delivery to reduce burden, (5) tailor visit frequency and monitoring intensity, (6) use telemedicine and alternative modalities when they still deliver guideline-based services, and (7) individualize monitoring, including self-monitoring when safe and feasible.

The document also makes several “quietly radical” statements that many clinics still do not act on:

Extra prenatal visits do not fix unmet social needs and can increase burden.

For average-risk women, evidence supports fewer targeted visits, with equivalent maternal and neonatal outcomes in systematic reviews.

There is no demonstrated stillbirth-prevention benefit to routine antenatal fetal heart rate checks or formal kick counts in low-risk settings, and fetal heart rate checks add limited clinical utility if fetal movement is reassuring.

Video telehealth is not proven superior to audio-only, and video can feel like surveillance to some patients.

Clinically, those are defensible positions. Operationally, they collide with how most prenatal clinics are staffed, reimbursed, scheduled, and measured.

The implementation problem. Good ideas, weak mechanism

ACOG repeatedly acknowledges implementation barriers: invisible visit modality in claims because of global billing, heterogeneity of outcomes, and the need to ensure tailoring does not improve efficiency “at the expense” of historically marginalized patients.

Here is the hard truth. Tailoring prenatal care is not primarily a clinical guideline problem. It is a payment, workforce, infrastructure, and accountability problem.

If you “tailor” by simply reducing visits, you risk under-serving high-risk women and those with low trust, unstable housing, low health literacy, or poor access to urgent evaluation. If you “tailor” by adding social screening without closing the loop, you burn out staff and disappoint patients. The document explicitly links insufficient resources to clinician burnout, and calls out reimbursement, resources, and workforce development as prerequisites.

Implementation table

Below is a practical translation of the consensus into “who does what, with what guardrails,” with Medicaid clinics explicitly in view.

Every recommendation depends less on clinical insight than on infrastructure, accountability, and follow-through. Whether in Medicaid clinics or offices accepting commercial insurance, tailoring prenatal care without defined guardrails risks either under-care or unmeasured variation. The implementation challenge is not knowing what to do. It is building systems that ensure it is done safely, equitably, and consistently.

Why Medicaid clinics are the make-or-break setting

Medicaid finances a very large share of U.S. births, commonly reported around 40 percent, and it disproportionately covers women facing transportation instability, unpredictable work schedules, language barriers, and higher medical comorbidity burdens. That makes Medicaid clinics the highest-yield environment for “tailoring,” and also the highest-risk environment for misapplication.

The consensus document’s most important Medicaid-relevant line is this: adding visits does not fix social need and can create burden.

In Medicaid clinics, the dominant failure mode is not “too few visits.” It is missed services because of access friction, and late recognition of complications because urgent pathways are unclear or distrusted.

A Medicaid-ready implementation blueprint

Define “essential services” and build the schedule around them. Make ultrasound, vaccines, and time-sensitive labs the fixed anchors, then layer counseling and anticipatory guidance through telehealth or group care. This aligns with the document’s emphasis that telemedicine is acceptable when guideline-based services are still completed.

Tailored Prenatal Care Delivery…

Risk stratify twice, not once. Do an early needs assessment, then reassess at defined gestational milestones and after any ED or triage visit. The consensus explicitly calls for reassessing risk and escalating care when needed.

Tailored Prenatal Care Delivery…

Treat remote BP monitoring as core infrastructure for hypertensive risk. The document supports more frequent BP checks for chronic hypertension and hypertensive disorders, and supports self-monitoring feasibility for BP and weight when patients have training, equipment, and a help pathway.

Tailored Prenatal Care Delivery…

Tailored Prenatal Care Delivery…

Build closed-loop social care referral as a quality requirement. ACOG notes that closed-loop processes outperform resource lists alone. Medicaid clinics should measure referral completion the way they measure glucose screening completion.

Tailored Prenatal Care Delivery…

Do not “efficiency” your way into inequity. ACOG explicitly warns implementation must not improve efficiency at the expense of marginalized patients. That is an outcomes and auditing mandate, not a slogan. Track outcomes and experience by race, language, and neighborhood deprivation from day one.

Offices accepting commercial insurance. Different constraints, similar risks

Offices that primarily accept commercial insurance often assume they are better positioned to implement tailored prenatal care. In some respects, they are. Visit length may be more flexible, staffing ratios may be better, and telehealth infrastructure is often already in place. However, the core implementation risks identified in the consensus still apply, just with different failure modes.

In privately insured settings, the dominant risk is over-customization without accountability. Tailoring can quietly become idiosyncratic care driven by clinician preference rather than evidence or structure. Visit frequency may drift upward rather than downward. Telemedicine may be offered selectively rather than equitably. Social needs screening may be omitted under the assumption that commercially insured women have fewer unmet needs, despite strong evidence that insurance status does not eliminate housing instability, food insecurity, or intimate partner violence.

Operationally, offices accepting insurance should implement the same guardrails recommended for Medicaid clinics, but with additional emphasis on standardization. Tailored care must still be anchored to clearly defined service bundles, mandatory escalation criteria, and documented reassessment points. Without those controls, tailoring risks widening inter-practice variation and undermining quality benchmarking. The consensus document implicitly acknowledges this by emphasizing that visit number alone is a poor proxy for quality, regardless of payer mix. The payer changes. The ethical obligation does not.

“Shared decision-making”

The phrase shared decision-making appears four times in the document.

Early care planning section. Shared decision-making is referenced as part of developing an individualized prenatal care plan after an early needs assessment.

Care delivery model discussion. It is cited as a principle guiding decisions about visit frequency, modality, and content.

Telemedicine and alternative modalities section. The term is used to justify offering different care modalities based on patient preference and feasibility.

Equity and patient-centeredness framing. Shared decision-making is invoked as a mechanism to avoid one-size-fits-all care and to respect patient values.

Was shared decision-making clearly defined?

No. The document does not provide a formal definition of shared decision-making.

Specifically:

There is no operational definition.

There is no description of required elements such as disclosure of options, discussion of risks and benefits, clinician recommendations, or documentation standards.

There is no distinction made between shared decision-making and informed consent, nor is there guidance on how disagreement between clinician recommendation and patient preference should be handled.

As a result, shared decision-making functions more as a normative signal than as an implementable clinical process. This is a notable gap. Without a clear definition, shared decision-making risks being interpreted as preference-following rather than responsibility-sharing. In the context of tailored prenatal care, that ambiguity matters. Tailoring without defined professional recommendations can quietly shift responsibility from the clinician to the patient, particularly in under-resourced settings.

A more robust implementation would have required the document to specify what shared decision-making means in prenatal care, how it differs from simple choice, and how clinicians should document and act when patient preferences conflict with evidence-based recommendations. That omission weakens an otherwise pragmatic consensus.

My critical bottom line

This consensus is directionally right. It recognizes that prenatal care is a bundle of services and relationships, not a visit count. It also admits the evidence base is thin in diverse, real-world populations and that implementation will not be immediate.

The risk is predictable. Health systems will cherry-pick the “fewer visits” headline because it looks like throughput, while underinvesting in the enabling conditions ACOG repeatedly flags: workforce support, reimbursement, equipment access, broadband, and closed-loop social care. If that happens, “tailored prenatal care” becomes the next well-branded way to ration time for the women who already get the least.

If you want this to work in Medicaid clinics, implement it like a safety intervention: define minimum service guarantees, build rapid escalation pathways, fund the infrastructure, and publish equity-stratified metrics. Anything less is a redesign in name only.

Verified references

Peahl AF, Smith RD, Moniz MH. Prenatal care redesign: creating flexible maternity care models through virtual care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(3):389.e1-389.e10. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.029. PMID:32425200. PubMed

Daw JR, Kozhimannil KB, Admon LK. High rates of postpartum uninsurance among women in the United States. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(6):e211054. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.1054. PMID:35977176. PMC