Stop Training Cancer Surgeons and Infertility Doctors to Deliver Babies

It’s time to separate surgical and obstetric training from subspecialization and build a workforce that matches what women actually need.

Every summer, a new class of freshly minted physicians enters obstetrics and gynecology residency. They have survived four years of medical school and are about to embark on another four years of intense, hands-on training.

The General Obstetrics & Gynecology Training

According to the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ABOG), those 48 months of general ObGyn training are divided roughly into 18 months of obstetrics, 18 months of gynecology, six months of primary and preventive care, and six months of electives or research. During those years, residents deliver hundreds of babies, perform hysterectomies, manage miscarriages, and master a range of office and surgical procedures.

In theory, the goal is to produce a “general” ObGyn—someone equally competent in delivering babies, performing surgeries, and providing routine reproductive care. But in reality, the landscape has shifted dramatically.

Half of those who finish residency go on to fellowships that focus narrowly on one aspect of the field, extending their training another three or four years. And will never do again the other half of their training. 50% of the 4-year training is wasted.

Let’s look at what those fellowships are.

Maternal–Fetal Medicine (MFM): These specialists manage high-risk pregnancies—women with diabetes, hypertension, twins, or fetal anomalies. Their training is heavily focused on ultrasound, genetics, and perinatal care. Most never perform routine gynecologic surgeries again.

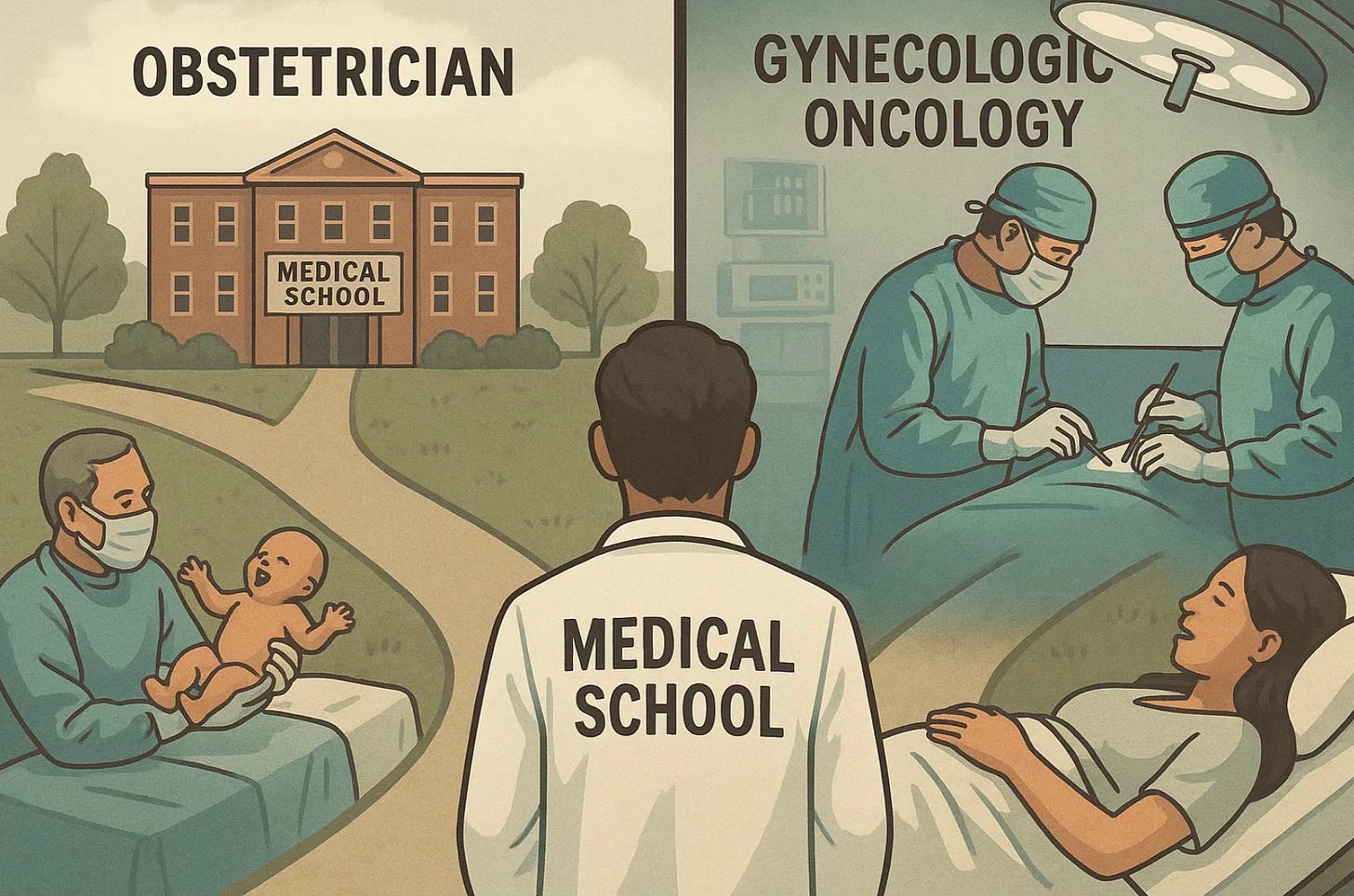

Gynecologic Oncology: This track trains surgeons who treat reproductive cancers. Fellows spend their years mastering radical operations, chemotherapy management, and postoperative care. Obstetrics plays almost no role in their practice.

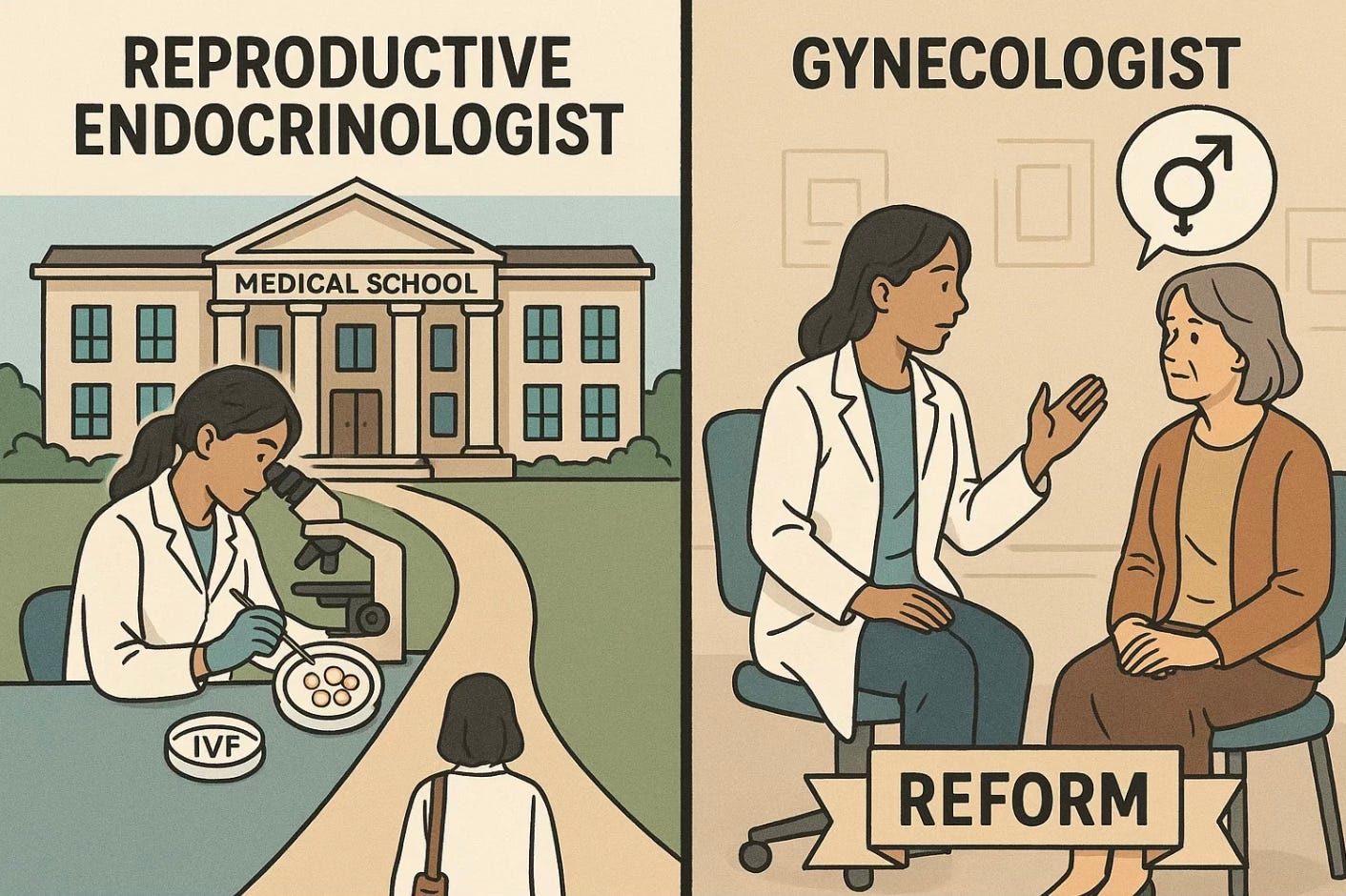

Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility (REI): REI physicians specialize in hormonal disorders, in vitro fertilization, and reproductive genetics. Their day-to-day work happens in labs and clinics, not delivery rooms.

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery (FPMRS): These surgeons repair pelvic floor disorders such as prolapse and incontinence. Their training involves complex reconstructive techniques, not labor management.

Complex Family Planning: This relatively new subspecialty focuses on contraception and abortion care. It is intellectually rigorous and politically charged—but not obstetric.

By the time these physicians complete both residency and fellowship, they have invested seven to eight years beyond medical school. And yet, more than half of that time was spent learning obstetrics skills they will never again use.

Some Findings

A few educators have questioned whether the current four-year ObGyn residency is the best use of time, but none have gone as far as proposing to eliminate obstetric training entirely for subspecialists. Studies of gynecologic oncology and reproductive endocrinology fellows have noted that many enter fellowship feeling underprepared in the surgical or scientific skills their future work demands, suggesting a mismatch between general residency content and eventual practice. Program directors and policy papers—particularly in Europe—have discussed modular or “track-based” training, in which residents could focus earlier on either obstetrics or gynecology, yet all existing models still require full certification in both before subspecialization. In other words, reform ideas exist, but the system remains rooted in a one-size-fits-all pathway that prioritizes historical precedent over efficiency. No major medical body, including ABOG or ACGME, has endorsed bypassing obstetrics altogether for future reproductive endocrinologists or gynecologic oncologists, making this proposal both novel and overdue for debate.

A Shortage of General ObGyns in the United States

Meanwhile, the United States faces a shortage of general ObGyns, the very doctors who still deliver babies and take care of women’s overall health. A recent AAMC report projects that by 2035, the shortfall may exceed 8,000. Many young physicians choose subspecialties not because they dislike general practice, but because it offers more predictable hours, fewer night calls, and significantly higher pay. A general ObGyn earns around $320,000 annually on average. Subspecialists often exceed $450,000 to $600,000. The incentives are obvious.

We have designed a training system that is both inefficient and mismatched to reality. More than 50 percent of residency time is devoted to obstetrics.

That makes sense for those who will deliver babies—but not for the half who won’t. Maternal-Fetal Medicince (MFM) aside, most subspecialists never again need to manage shoulder dystocia or interpret a fetal heart tracing.

Yet every future reproductive endocrinologist or every gynecologic oncologist must first spend years catching babies at 3 a.m. Only to never do it again in their subspecialty.

It is as if we required every future cardiologist to spend half of residency delivering babies before being allowed to touch a stethoscope.

If we were building medical training from scratch today, we would design a modular system. Graduates could enter a focused track in their chosen field directly after medical school: obstetrics, gynecologic surgery, fertility, oncology, or pelvic reconstruction. Those who want to deliver babies would still complete full obstetric training, but others could bypass it entirely. Instead of 7–8 years, subspecialists could be fully trained in 5–6, or even less for some subspecialties like reporoductive medicine. We could save 2-3 years for each, and focus more on what they actually will do for the rest of their professional lives.

Take Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility (REI).

This field has almost nothing to do with obstetrics as traditionally defined. REI physicians spend their careers diagnosing and treating infertility, hormonal disorders, polycystic ovary syndrome, endometriosis, and early menopause. They perform complex laboratory procedures like in vitro fertilization (IVF), egg retrieval, embryo transfer, and preimplantation genetic testing. Their expertise lies in reproductive physiology, molecular biology, embryology, endocrinology, and assisted reproductive technology, not in labor management or obstetric emergencies. The REI environment is outpatient and laboratory-based, with no need for obstetric call schedules, fetal monitoring, or cesarean deliveries. Every hour a future REI fellow spends on a labor floor is an hour not spent mastering ovarian stimulation protocols, culture media optimization, or embryo grading.

Training REIs in obstetrics is as inefficient as teaching a cardiac electrophysiologist to deliver twins. Or inefficient as training an orthopedic surgeon to do gynecologic cancer surgery.

If we designed an REI curriculum directly after medical school, it could likely be completed in four to five years, integrating reproductive physiology, minimally invasive surgery, endocrinology, genetics, and the psychosocial aspects of fertility care. No radical cancer surgery, no complicated pregnancies cesareans and deliveries. Such a pathway would not only accelerate readiness but also align training with actual practice, producing more specialists sooner, at lower cost, and with greater professional satisfaction.

Take Gynecologic Oncology

Gynecologic Oncology presents a similar case. These physicians dedicate their careers to diagnosing and surgically treating cancers of the uterus, cervix, ovaries, and vulva. Their expertise is in radical pelvic surgery, chemotherapy, and complex postoperative care, not in obstetrics. The skills required to manage labor or perform a cesarean section have no overlap with those needed to perform a radical hysterectomy or cytoreductive surgery. A focused oncologic training pathway beginning right after medical school could be completed in about four to five years, integrating surgical oncology, pathology, genetics, and palliative care.

Requiring years of obstetric training form cancer surgeons before this serves neither efficiency nor patient care; it only delays when future cancer specialists can start doing the work they were meant to do.

This idea isn’t radical. In most of Europe, subspecialization begins earlier and training is shorter. The result: a more efficient, targeted workforce and less burnout. The U.S. model, by contrast, treats every future ObGyn as if they must be ready for a delivery at any moment, even if they plan to spend their careers in research labs or cancer centers.

Some will argue that early specialization narrows experience or limits perspective. True, but that is perspective not needed or required later on. The real danger is the opposite: wasting years of potential in the wrong training environment. A resident spending nights managing low-risk labor when they could be learning embryo biology or robotic surgery is not gaining “breadth”, they’re losing time.

If we want to solve the dual crisis of ObGyn shortages and workforce inefficiency, we need to align training with practice. That means creating two distinct pathways: a full-spectrum ObGyn track for those who intend to deliver babies and a direct-entry subspecialty route for those who do not.

The women we care for deserve doctors whose training fits their needs—not a one-size-fits-all model built in the 1950s.

Reflection / Closing:

If the goal of medicine is to use time wisely, for both doctors and patients, then our current ObGyn training model is an ethical failure of efficiency. Are we educating physicians to meet the realities of women’s health, or merely preserving tradition because it feels safe?

That no one has dared to suggest this before says more about our professional inertia than about the idea itself. Medicine changes only when inefficiency becomes unbearable, and we are nearly there.

Everyone quietly admits that training future reproductive endocrinologists or cancer surgeons to manage labor is absurd, yet we persist because institutions like ABOG and ACGME move at the speed of tectonic plates.

Bureaucracies defend tradition long after the facts have changed. The result is a system that spends hundreds of millions of dollars and thousands of physician-years teaching skills that will never be used. If economists called this what it is, a misallocation of human capital, it would sound less polite but more accurate. The challenge now is not whether the idea is radical, but whether we have the courage to acknowledge that it’s rational.

There may be some down sides but not nearly as much as the upside. I agree! Lets make residency applicable to the subspecialty if you know that’s what you want

Interesting and valid points. To counter this, I find that a lot of residents use their time in residency to sort out where exactly they want their specialty to be. We might be losing out on potential OB GYNs if they don’t get the exposure to the field.