Robots, Ultrasound, and the Real Problem in Rural Maternity Care

When a machine enters obstetrics, the question is not technology. The question is access.

The Alabama proposal

Alabama recently proposed using “robotic ultrasound” as part of a rural maternal health initiative after many of its counties lost obstetric services. The idea, discussed at a federal rural health funding roundtable, immediately triggered polarized reactions. Some described it as innovation, others as a dystopian replacement for physicians.

In reality, the state is not planning autonomous machines delivering obstetric care. The proposal aims to allow a remote sonographer or physician to perform an ultrasound on a pregnant woman in a clinic that has no local imaging capability.

The Alabama proposal triggered reactions because people imagined an automated obstetrician. That is not what is being proposed. What is being proposed is remote image acquisition in places where no one locally can perform an ultrasound.

The issue, plainly defined

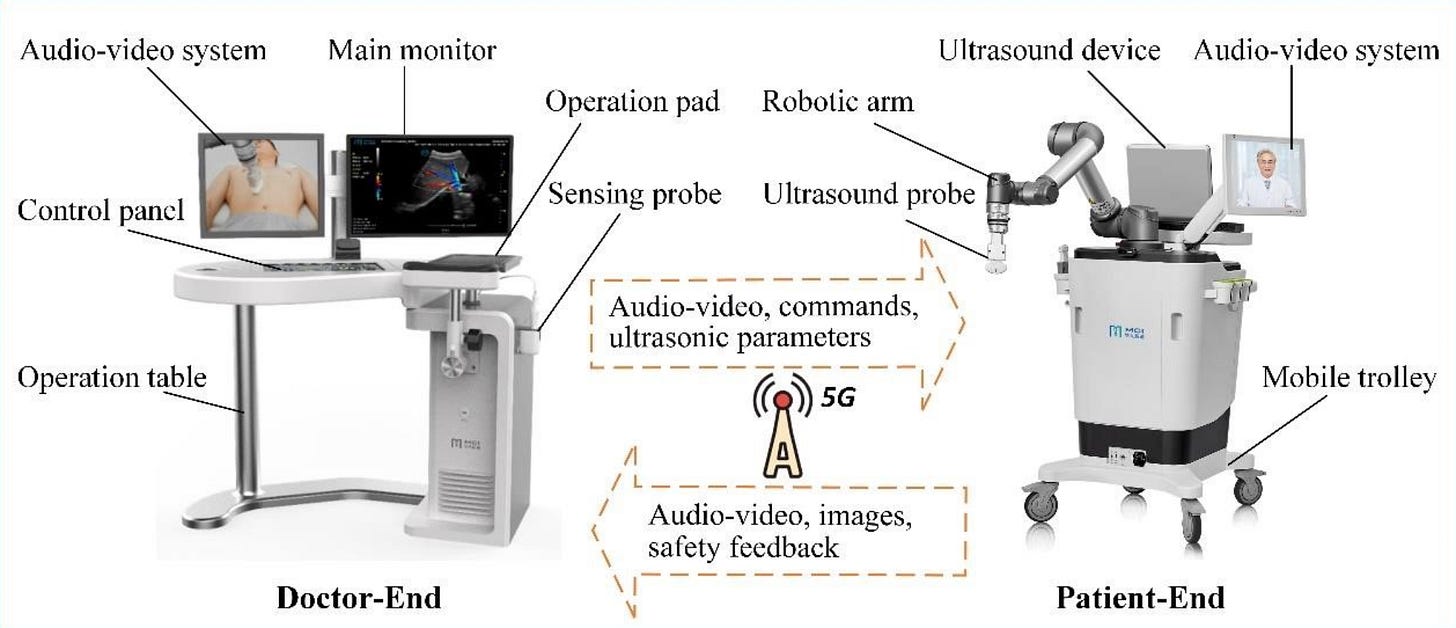

A “robotic ultrasound” is not a robot practicing medicine. It is a remotely controlled ultrasound probe. A trained sonographer or physician sits at a distant console and moves the probe in real time while a nurse or assistant is with the pregnant woman in the clinic. The images are transmitted live and then interpreted by a clinician. The device does not diagnose. It does not decide. It does not manage pregnancy. It only allows someone far away to hold the probe.

Why this is happening

The background is not technology. The background is geography and workforce.

Across rural America, obstetric units have closed for years. When a hospital closes its labor unit, obstetricians, anesthesiology coverage, neonatal support, and ultrasound capability disappear together. After that, prenatal care becomes fragmented. A pregnant woman may have prenatal visits but no imaging, or delayed imaging, or travel several hours for a basic anatomy scan.

Ultrasound is not a luxury in pregnancy. It establishes gestational age, identifies multiple gestation, detects placenta previa, screens for growth restriction, and identifies major anomalies. Without it, clinicians are managing pregnancy with incomplete information.

The proposed use of telerobotic ultrasound is meant to restore at least the first layer of prenatal evaluation, namely identifying which pregnancies are high risk and need transfer.

What the technology can and cannot do

Telerobotic ultrasound can obtain standard abdominal images. It can confirm dating. It can identify breech presentation. It can screen for major structural anomalies and abnormal growth. In a community without imaging, this is clinically meaningful because it changes referral decisions and timing of transport.

It cannot perform transvaginal ultrasound. It cannot evaluate acute bleeding well. It cannot manage preeclampsia, diabetes, labor, or hemorrhage. It does not replace maternal fetal medicine consultation and does not substitute for a functioning obstetric service. If internet connectivity fails, the examination stops immediately. The machine does not continue independently because there is no independent function.

The device therefore addresses one specific problem. Lack of diagnostic imaging. It does not address the larger problem, which is absence of a maternity care system.

The debate is misframed

The public conversation has become a technology argument. It is not actually about robots. It is about what happens when a health system loses clinicians but still has patients.

If a county has no obstetrician, the choice is not between a bedside specialist and a robot. The choice is between remote imaging and no imaging. The correct comparison is not ideal care versus technological care. It is incomplete care versus slightly less incomplete care.

At the same time, clinicians are correct to be cautious. Ultrasound is not purely technical image acquisition. Bedside clinical assessment matters. Subtle findings are often interpreted within the clinical context, including blood pressure, symptoms, and examination. A remote scan cannot reproduce that environment.

What it actually means

Telerobotic ultrasound is best understood as a triage tool. Its purpose is early recognition of risk so that transfer can occur before labor, hemorrhage, or fetal compromise. It does not reduce the need for obstetricians. In a functioning system it would be temporary support, not a replacement workforce.

The concern many physicians express is therefore not technological safety. It is policy substitution. If technology becomes a reason not to rebuild the maternity workforce, outcomes will not improve. A probe held from 200 miles away cannot deliver a baby, treat postpartum hemorrhage, or manage severe hypertension.

The machine answers one question: “Is this pregnancy high risk?”

It cannot answer the next one: “Who will care for her when it is?”

The practical conclusion

Rural maternity care currently faces a structural shortage of clinicians. Telerobotic ultrasound attempts to mitigate one specific gap, access to prenatal imaging. Used appropriately, it may help identify dangerous conditions earlier and direct transfer.

But it is not a maternity care model. It is a diagnostic bridge.

The real debate should not be whether robots belong in obstetrics.

It should be why some communities have pregnancies but no obstetric care, and why technology is being asked to compensate for a workforce that no longer exists.