Positive HPV, Negative Pap: What Do We Do Next?

When one test says “risk” and the other says “normal,” the right answer is not reassurance—it’s responsibility. The Responsibility Clause — Ethical reasoning at the crossroads of autonomy, and duty.

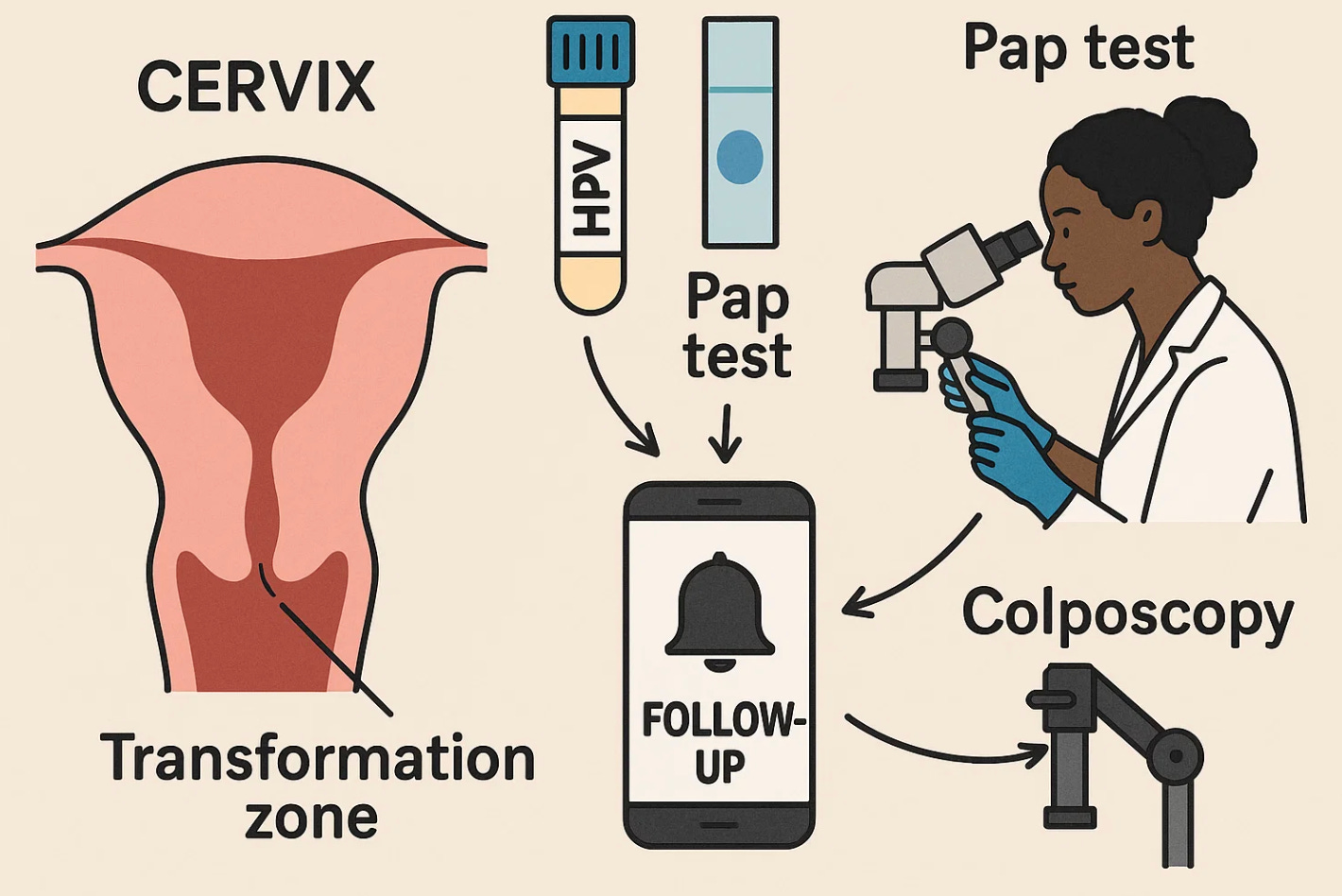

When it comes to cervical cancer screening, two tests work together to protect women. The HPV test looks for the presence of the human papillomavirus, a very common infection that can cause cervical cancer. High-risk HPV types, especially types 16 and 18, are responsible for most precancerous and cancerous changes of the cervix. The Pap test (or Pap smear) looks at actual cells from the cervix under a microscope to see if any look abnormal or precancerous. In short, the HPV test finds the virus; the Pap test looks for the damage it may have caused.

Because the Pap test examines only a small number of cells, it can sometimes miss early disease, especially if abnormal cells haven’t yet developed or were not collected in the sample. The HPV test, on the other hand, can be positive years before any visible cell changes appear. This is why both tests are often done together, and why their combination must be interpreted carefully. A “normal” Pap with a positive HPV test doesn’t mean everything is fine—it means the virus is there but hasn’t yet changed the cells.

That is exactly what happened to one patient. A 29-year-old woman came for her routine exam. Her Pap smear was negative, but her HPV test was positive for high-risk types. She was told to return in a year. The advice sounded reasonable—until it wasn’t. Within two years, she developed symptoms, was diagnosed with invasive cervical cancer, and died in her mid-30s. The tests were right, but the follow-up was wrong.

According to the 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Guidelines, if the HPV test is positive but the Pap is normal, the next step is clear: repeat testing in one year. If the HPV result stays positive, or if HPV types 16 or 18 are found, a colposcopy should be done right away. In this case, the patient’s second clinician did not realize there had been an earlier abnormal result. Without linking both results together, the system failed her.

A colposcopy is a simple, office-based procedure that lets a doctor look closely at the cervix using a magnifying instrument called a colposcope. The doctor applies a mild vinegar-like solution that makes abnormal areas turn white and easier to see. If anything looks suspicious, tiny tissue samples (biopsies) are taken for testing. The goal is to find changes in the transformation zone—the area where the outer squamous cells of the cervix meet the inner columnar cells. This is where almost all cervical cancers begin. The Pap looks at cells, the HPV test finds the virus, and the colposcopy shows where it is actually causing harm.

HPV itself is not an emergency, but it is a signal that needs follow-up. Most infections clear on their own within a year or two, but if high-risk HPV stays in the body, it can slowly cause precancerous changes. Two consecutive positive HPV results—even with normal Pap smears—mean a 4–5 percent chance of developing a high-grade precancer (CIN 3 or higher) within five years. That may sound small, but in population terms, it’s a clear reason for closer evaluation.

The ethical issue is not just clinical—it’s about accountability. When a woman moves or changes doctors, her previous results must be reviewed and connected. Responsibility for follow-up cannot disappear when records do. Each test is more than data; it’s a promise to act on what the data reveal.

Artificial intelligence may soon strengthen that promise. A.I.-enabled health record systems can already track abnormal results across clinics, flag missed follow-ups, and send reminders to both patients and clinicians. Properly designed, they can act as a safety net that keeps results from falling through the cracks. But no algorithm replaces professional attention—or clear communication.

Patients often hear “normal” and assume “safe.” That’s where counseling matters most. The right message is: “Your Pap looks normal, but your HPV test shows a virus that can cause changes in the future. We need to check again in a year, and if the virus remains, we’ll do a colposcopy to look more closely.” Clarity prevents false reassurance and keeps shared vigilance alive.

Medicine is not only about detecting disease; it’s about never missing the chance to prevent it. A positive HPV test and a normal Pap are not contradictions—they’re two halves of one story. Our ethical task is to connect them before the disease does.

And while physicians must act on every result, patients share the responsibility. Every woman should know her exact results, keep copies of them, and ask whether her care plan follows official guidelines. Generative A.I. tools can now help patients organize records, set reminders for follow-up testing, and translate reports into clear language.

TIP: Take an image of your results, then copy it into let’s say ChatGPT and ask it to read it and interpret it.

Here is an example prompt:

“Interpret the attached Pap smear result, explaining in clear clinical and patient-centered terms what the findings mean, whether HPV testing was performed or indicated, what the recommended next step should be according to ACOG/ASCCP guidelines, and whether colposcopy or repeat testing is appropriate.”

Empowered patients do not replace doctors, but they make care safer. The best prevention happens when both sides—doctor and patient—work as partners to close every loop before it becomes a loss.

Standard of care: Pap test and HPV test (as of October 2025)

How ACOG defines the tests

“A Pap test looks for abnormal cells. An HPV test looks for infection with the HPV types that can cause cancer.” ACOG

“Cervical cancer screening includes the Pap test, an HPV test, or both.” ACOG

Who to screen and how often, average-risk

ACOG endorses the USPSTF schedule and states: “There are now three recommended options for cervical cancer screening in individuals aged 30–65 years: primary hrHPV testing every 5 years, cervical cytology alone every 3 years, or cotesting every 5 years.” ACOG

Ages 21–29: screen with cytology alone every 3 years. For ages 30–65, any of the three strategies above are acceptable. These intervals are the same schedule USPSTF issues Grade A recommendations for. USPSTF

When screening may stop or differ

Stop screening after 65 if there is adequate prior negative screening and no history of CIN2+; do not screen if there has been a total hysterectomy with cervix removed for benign reasons. Patients with HIV, immunocompromise, prior cervical cancer, or DES exposure need more frequent or longer screening. ACOG patient materials summarize these exceptions for clinicians and patients. ACOG+1

Reflex testing and genotyping

ACOG patient guidance: “If you had a Pap test, an HPV test may be done on the same cells used for the Pap test. This is called reflex testing. HPV typing is another kind of HPV test that looks for types 16 and 18.” ACOG

Management when results are discordant or abnormal (ASCCP, endorsed by ACOG)

ASCCP 2019 risk-based consensus: “Repeat HPV testing or cotesting at 1 year is recommended for patients with minor screening abnormalities indicating HPV infection with low risk of underlying CIN 3+.” If the abnormality persists at 1 year, refer to colposcopy. PMC

“HPV 16 or 18 infections have the highest risk for CIN 3” and typically warrant immediate colposcopy even when cytology is NILM. ASCCP

Plain-Language Summary: Understanding Pap and HPV Results

Cervical cancer screening helps find problems early—often before they become dangerous. The two main tests are the Pap test, which looks at cervical cells for any signs of abnormality, and the HPV test, which looks for the human papillomavirus that can cause those cell changes. Here’s what to know about all common results and what they mean:

1. Pap and HPV both negative (normal):

This is the best result. It means your cervix looks healthy and no high-risk HPV is detected.

→ What to do: If you’re age 30–65, repeat screening in 3 years (Pap alone) or 5 years (HPV or both).

2. Pap normal but HPV positive:

This means you have the virus, but your cervical cells still look normal. Most infections go away on their own, but some can cause future problems.

→ What to do: Repeat both tests in 1 year. If HPV stays positive or if testing shows types 16 or 18, a colposcopy is recommended to look more closely at the cervix.

3. Pap abnormal (ASC-US, LSIL, etc.) but HPV negative:

Your cells look slightly different, but the virus that causes most cervical cancers isn’t there.

→ What to do: Usually, repeat testing in 3 years is safe. Your doctor may individualize follow-up depending on your history.

4. Pap abnormal and HPV positive:

This means both the virus and abnormal cells are present.

→ What to do: A colposcopy is needed to check for precancerous or cancerous changes. The risk is higher, so follow-up should not be delayed.

5. Pap test shows “high-grade” changes (HSIL or worse):

This suggests a strong chance of precancer.

→ What to do: Immediate colposcopy or diagnostic treatment (such as a LEEP) is recommended even if the HPV result is missing or negative.

6. HPV 16 or 18 positive (even if Pap is normal):

These types carry the highest risk for cervical cancer.

→ What to do: Colposcopy is recommended without waiting for repeat testing.

7. Unsatisfactory Pap test (not enough cells):

This means the lab couldn’t read your sample properly.

→ What to do: Repeat the Pap in 2–4 months.

8. Missing or incomplete HPV result:

Sometimes the lab runs only one test or results get lost.

→ What to do: Ask your provider to confirm both results are documented before assuming all is normal.

When to Stop Screening

You may stop screening after age 65 if you’ve had three normal Pap tests in a row or two normal HPV-based tests in the past 10 years, and no history of CIN2+ (precancer).

You do not need screening if you had a total hysterectomy with removal of the cervix for non-cancer reasons.

Women with HIV, weakened immunity, prior cervical cancer, or DES exposure need more frequent screening.

What ACOG Says

“Cervical cancer screening can be done with a Pap test, an HPV test, or both together. Starting at age 21, people with a cervix should have regular screening every 3 to 5 years depending on age and testing method.” — ACOG Practice Advisory: Updated Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines, April 2021

“For most individuals aged 30 to 65 years, primary high-risk HPV testing every 5 years, cytology alone every 3 years, or co-testing every 5 years are all acceptable.” — ACOG and ASCCP Consensus, reaffirmed 2024

Key Takeaway

Screening saves lives only if both doctors and patients act on results.

Keep your test reports, ask for both your Pap and HPV results, and know when to return. If results are unclear or abnormal, confirm that a colposcopy or repeat test is scheduled.

Artificial intelligence systems now help track results and remind both patients and clinicians when it’s time for follow-up—but your attention remains the most important safety net.