The Human Factor: We Don’t Tell Patients the Real Numbers

Doctors and patients often speak different languages when it comes to risk.

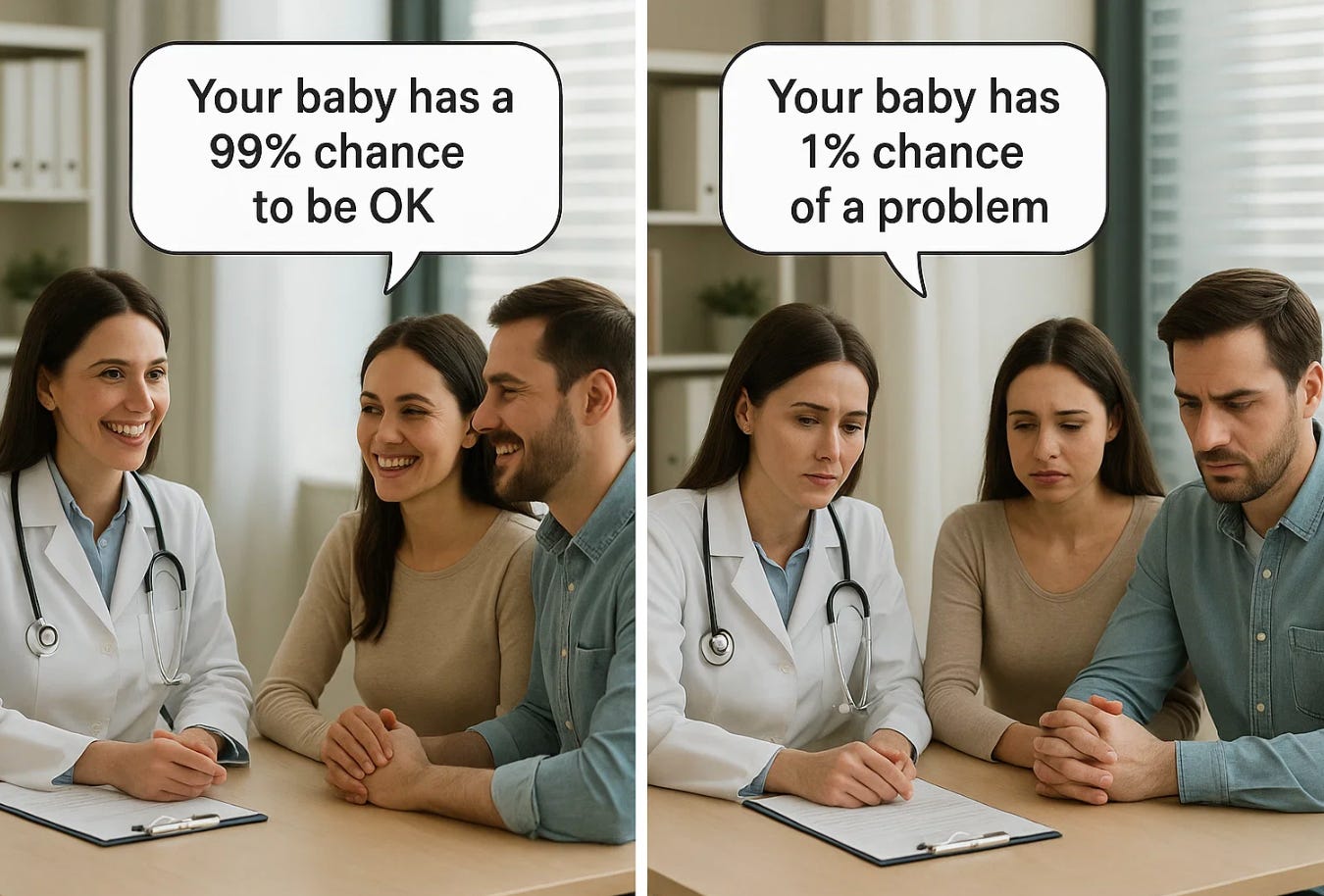

Doctors and patients often speak different languages when it comes to risk. A physician says, “This complication rarely happens.” A patient wonders, “Does that mean one in 100? One in 1,000? One in 10,000?” When we use vague words, we leave patients guessing. That guesswork can distort decisions and undermine trust.

How Doctors Talk About Frequency

In daily practice, we use soft language—“sometimes,” “usually,” “never”—to describe how often things occur. It feels gentler than rattling off percentages. But here is the problem: those words don’t mean the same thing to everyone.

When a doctor says “never,” they often mean “extremely unlikely.” When a patient hears “never,” they may assume the risk is literally zero. The same with “always.” In medicine, nothing is always true. Even when we say “almost always,” exceptions exist.

This imprecision creates a dangerous gap. Patients may consent to or refuse interventions based not on evidence, but on their personal interpretation of a word.

The Language of Frequency

Surveys of both doctors and patients show that the following words are interpreted with wide variation. To illustrate, I’ve listed approximate ranges of how people interpret them, not absolute truths:

Always: usually taken as 90–100%, though rarely literally 100%

Never: usually taken as 0–1%, though rarely literally 0%

Almost always: 80–95%

Usually: 60–80%

Often: 40–60%

Sometimes: 20–40%

Occasionally: 10–20%

Rarely: 1–10%

Very rarely: 0.1–1%

Extremely rare: less than 0.1%

Notice how much these ranges overlap. “Rare” to one physician may mean 1 in 100, while another uses it to mean 1 in 5,000. Without numbers, patients cannot know.

Example 1: Fever and Neural Tube Defects

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advises pregnant women to take acetaminophen when they have a fever. The reason is to reduce the risk of neural tube defects (NTDs). But the guideline uses words, not numbers.

Here are the numbers:

Baseline risk of NTDs in the U.S. is about 1–2 in 1,000 births (0.1–0.2%).

Studies suggest that fever in the first trimester may roughly double that risk, making it 2–4 in 1,000 births (0.2–0.4%).

Now let’s frame it differently. With fever in early pregnancy, about 996 to 998 babies out of 1,000 will not have an NTD. Only 2–4 will. That is what “doubling the risk” actually means.

Put another way, even with fever, 99.6% to 99.8% of pregnancies will not result in an NTD. The relative increase sounds dramatic, but the absolute difference is small. Saying “fever doubles the risk” without explaining the baseline makes it sound like a catastrophe is likely, when in reality it remains uncommon.

And here’s the irony: for many patients, “996 out of 1,000 will be fine” can feel like “never happens.” For others, those 2–4 cases loom large. Words like “never” or “rarely” cannot capture that difference in perspective. Only numbers can.

Example 2: VBAC and Uterine Rupture

Women considering vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) are often told that uterine rupture is “rare.” But evidence shows the risk is about 0.5–1%, or 5–10 in 1,000.

That means 990 to 995 women out of 1,000 will not rupture. But for the 5–10 who do, the outcome can be catastrophic. Some women, hearing “rare,” assume it means virtually impossible. Others, when told “1 in 100,” may feel it is far too risky. Without numbers, “rare” leaves too much room for interpretation.

Example 3: Cesarean Complications

After cesarean delivery, women are told that bleeding, infection, or blood clots “sometimes” occur. But here are the numbers:

Infection: 2–7% (20–70 in 1,000).

Blood clots: 0.1–0.3% (1–3 in 1,000).

So 930 to 980 out of 1,000 women will not have an infection. And 997 to 999 will not have a blood clot. Yet the same word, “sometimes,” is used for both. That creates confusion.

Example 4: Genetic Testing Accuracy

Prenatal genetic testing is often described as “almost always correct.” But accuracy depends on the test:

Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) for Down syndrome: over 99% detection rate.

NIPT for rarer microdeletions: closer to 70–80%.

To a patient, “almost always” may sound like 100%. But the difference between 99% and 70% accuracy is enormous when making reproductive decisions. Patients need the numbers, not just the words.

Example 5: Preeclampsia and Seizures

When diagnosing preeclampsia, patients may be told that seizures “rarely” happen if blood pressure is monitored. In fact, the risk of eclampsia in women with severe preeclampsia, even under modern management, is around 1–2% (10–20 in 1,000). That means 980 to 990 women out of 1,000 will not seize, but the 10–20 who do may face life-threatening consequences. Again, “rare” is not enough.

Example 6: Risk of a baby’s death with home birth

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) supports the option of home birth. They say that with home birth 99.5% do not die as compared to 99.95% at hospital births. Evidence shows that neonatal mortality rises nearly tenfold in home births, even more so when there are risks. A home birth increases neonatal mortality from ~0.05% to ~0.5%. In that context, the AAP describes the increased risk of home births as negligible.

Why Evidence-Based Numbers Matter

Numbers anchor reality. They make risk concrete. If a patient hears “rare,” they may imagine one chance in a million and dismiss the concern. If they hear “rare, about 1 in 500,” they may think very differently.

Evidence-based numbers also prevent overstatement. Saying “always” or “never” ignores biology’s variability. Even antibiotics do not “always” work. Even genetic syndromes do not “never” occur outside family history. Every condition has exceptions.

In ethics, informed consent means honest disclosure of risks and benefits. Words without numbers are not enough. Patients cannot give fully informed consent if they do not know the true magnitude of a risk.

Why Doctors May Avoid Numbers

There is another reason doctors so often use vague words: many of us don’t know the exact numbers. Risks are not always neatly pinned down. Different studies may show different results depending on the population, the definitions used, or the quality of the research.

For example:

The risk of uterine rupture with VBAC ranges from 0.3% to 1% depending on the study design.

Infection after cesarean may be 2% in one hospital and 7% in another depending on antibiotics, sterile technique, and patient health.

Even the link between fever and NTDs varies across studies. Some show doubling, others show smaller effects.

This uncertainty is not a failure. It is the reality of medicine. But instead of replacing numbers with vague words, we should be transparent: give evidence-based ranges and explain why the numbers differ. Patients understand uncertainty if we explain it honestly. What undermines trust is pretending that vague words are clearer than imperfect data.

The Ethical Responsibility of Doctors

Behind all of this lies a deeper question: what do we owe our patients?

Doctors have an ethical responsibility not only to share medical facts but to share them in ways that are both accurate and meaningful. When we rely on vague language—“rare,” “always,” “never”—we may think we are simplifying, but in truth we are withholding. Patients cannot make informed decisions if we fail to tell the whole truth.

The “whole truth” means more than listing complications. It means giving both the relative and absolute risks, putting numbers into context, and explaining what those numbers mean for the individual sitting in front of us. It means acknowledging uncertainty when evidence is limited, rather than hiding behind comfortable generalities.

To say “fever doubles the risk of NTDs” without adding that 996 out of 1,000 babies will still be unaffected even without acetaminophen is incomplete. To say “rupture is rare” without explaining that it occurs in 5–10 out of 1,000 VBACs is misleading. To say “never” when the chance is low but not zero is careless. To say, like the American Academy of Pediatrics did, that the risk of home birth is low, and neonatal deaths increase only from 99.45% to 99.55%, for example, does not reflect the risk of neonatal deaths is 5-10 times higher in home birts compared to hospital births, and even higher with certain risks.

Ethics in medicine is not only about big debates like abortion or end-of-life care. It is also about the honesty of everyday conversations. Every time we discuss risk, we are shaping choices that affect lives. Every word matters.

Beyond Words: What Daniel Kahneman Teaches Us

Words shape choices. Numbers clarify them. Patients deserve more than comfort phrases like “rarely” or “never.” They deserve evidence-based numbers, paired with plain language, so they can truly understand their risks and make informed decisions.

And here’s the deeper point: for many patients, 996 out of 1,000 can feel like “never”—while for others, those 4 cases out of 1,000 are the only thing that matters. That is why medicine must move beyond vague words to honest numbers.

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman, who won the Nobel Prize in economics, spent his career showing how human beings are terrible at judging risk. His work revealed two consistent patterns:

We fear small risks too much when they are vivid (like a plane crash or a uterine rupture).

We ignore common risks when they feel ordinary (like infection after surgery or high blood pressure in pregnancy).

This isn’t stupidity. It’s human psychology. Our brains are wired to overreact to dramatic dangers and to downplay everyday ones. Kahneman called this “System 1 thinking”—fast, emotional, intuitive. But when it comes to medical decisions, we need “System 2”—slow, deliberate, numerical.

That’s why vague words like “rare” or “often” are so dangerous. They play directly into our biases. “Rare” may sound like “safe” to one patient and like “looming disaster” to another. Without numbers, our brains fill in the blanks—usually in ways that Kahneman showed are predictably wrong.

The ethical responsibility of doctors, then, is not just to give facts but to help patients think more like statisticians, not gamblers. That doesn’t mean handing them a math textbook. It means pairing words with actual numbers, showing both relative and absolute risks, and explaining ranges when the science is uncertain.

When we do that, we honor both science and human psychology. We respect informed consent not only in principle but in practice. We help patients see risk as it really is, not as fear or hope might distort it.

The ethical question is simple: if we know how easily words mislead, are we complicit in that distortion when we stop short of giving numbers? Or do we have a duty, as Kahneman urged in all decision-making, to “think slow” and help our patients do the same?

What We Can Do Better

Pair words with numbers. Instead of “rare,” say “rare, about 1 in 500.”

Use evidence-based ranges. Cite data from guidelines, registries, and studies. Not just impressions.

Avoid absolutes. Replace “always” and “never” with “almost always” or “extremely unlikely,” and then back it up with evidence.

Explain in context. Compare risks to familiar ones: “Your risk of a blood clot after cesarean is about 1 in 1,000—similar to the risk of being injured in a car accident in a year.”

Standardize language. Regulatory agencies like the European Medicines Agency define “common” (1–10%) and “very rare” (<0.01%). Obstetrics should do the same.