Measles Is Back. Here Is What Every ObGyn and Every Pregnant Patient Needs to Know.

From preconception immunity to fetal risk in pregnancy, the numbers are not what most people think they are.

The Numbers Right Now (February 2026)

As of February 19, 2026, the CDC has confirmed 982 measles cases in 26 states. That is more than four times the case count at the same point last year. 2025 ended with 2,281 confirmed cases, the highest annual total since 1992. We are on track to exceed that. South Carolina alone accounts for nearly 800 of the current cases, tied to a single outbreak exceeding 970 total infections, the largest in a generation. Ongoing clusters in Utah, Arizona, and Florida continue to grow.

This is not a background news story. It is a clinical situation that belongs in every preconception counseling visit and every obstetric intake form right now.

Why Measles Is an ObGyn Problem

Measles during pregnancy carries risks that most patients, and frankly many clinicians, underestimate. The virus itself is not teratogenic in the way rubella is. Measles does not cause a recognizable pattern of congenital malformations. But do not mistake that for safety.

Measles in a pregnant woman significantly increases the risk of spontaneous abortion, especially in the first trimester. It increases the risk of preterm labor and preterm birth. Maternal measles pneumonia, which occurs in a higher proportion of pregnant women than in non-pregnant adults, carries a case fatality rate that was historically estimated between 0.1% and 0.2% in healthy adults, but measles pneumonia in pregnancy can be severe and was a leading cause of measles-related maternal death in pre-vaccine era data.

Measles infection near term can result in neonatal measles, with transmission from mother to newborn perinatally. Neonatal measles in the first 10 days of life, before maternal antibody transfer is complete, is associated with higher severity. There is also evidence, confirmed in a landmark 2019 Science paper, that measles infection causes “immune amnesia,” destroying 10% to over 70% of a person’s existing immune memory against other pathogens, with vulnerability persisting for two to three years after recovery. A newborn whose mother had measles near delivery may arrive with a compromised immune foundation.

These are not theoretical risks. They are documented outcomes with measles circulating at the current level in 26 states.

How Measles Spreads and Your Actual Chances of Getting Infected

Measles is the most contagious respiratory virus known to infect humans.

It spreads through the air when an infected person breathes, coughs, or sneezes, and the virus remains active and infectious in the air and on surfaces for up to two hours after the infected person has left the room. You do not need direct contact. You do not even need to be in the room at the same time.

The virus’s basic reproduction number is estimated at 12 to 18, meaning one infected person in a fully susceptible population will transmit to an average of 12 to 18 others. By comparison, influenza’s reproduction number is roughly 1.2 to 1.4. If you are unvaccinated or non-immune and you are exposed to a confirmed measles case, your risk of infection is approximately 90%, or 9 out of 10. That is not a theoretical estimate.

It is the attack rate documented consistently across outbreak investigations.

A 2023 school outbreak in France found a 100% attack rate among unvaccinated children who were exposed. PubMed Central

For vaccinated individuals the picture is completely different. A 2024 systematic review in Emerging Infectious Diseases found that among people exposed to measles from a vaccinated person who had experienced vaccine failure, secondary attack rates were 0% to 6.25% CDC, reflecting the dramatically lower transmissibility when immunity is present even at waned levels. The practical translation: if you are unvaccinated and in a room where someone with measles has been, assume exposure. If you have two documented doses of MMR, your risk is low but not zero, and you should monitor for symptoms for 21 days.

Who Is Actually Immune, and How to Find Out

The first question every ObGyn should be asking before conception, and at the first prenatal visit, is: what is this patient’s measles immune status? The answer is not always what the patient believes.

Born before 1957: The CDC considers these patients to have natural immunity based on population-level exposure before the vaccine era. That presumption is clinically reasonable. No documentation or titer required for general purposes, though immunocompromised patients in this group warrant individual assessment.

Born in 1957 or later, with documentation of two MMR doses: This is the strongest basis for presumed immunity. Two doses of MMR vaccine are approximately 97% effective against measles. A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis in The Journal of Infectious Diseases found no statistically significant decline in detectable antibodies up to 17 years after the second dose, and modeling estimated antibody concentrations may remain protective for approximately 50 years after the last dose. Memory B cells and memory T cells add a layer of protection that serum antibody levels alone do not fully capture.

Born 1963 to 1967, uncertain vaccine type: A small subset of people vaccinated during this window may have received the inactivated (killed) measles vaccine, which was withdrawn because it was less effective and could actually predispose to atypical measles on wild-type exposure. If your patient is in this age range and cannot confirm which vaccine they received, they should be considered at risk and tested or re-vaccinated.

Single-dose history (vaccinated 1963 to 1989): One dose is approximately 93% effective individually. This is meaningful protection, but a second dose is appropriate for anyone in this category who works in healthcare, has not completed the two-dose series, or is planning pregnancy.

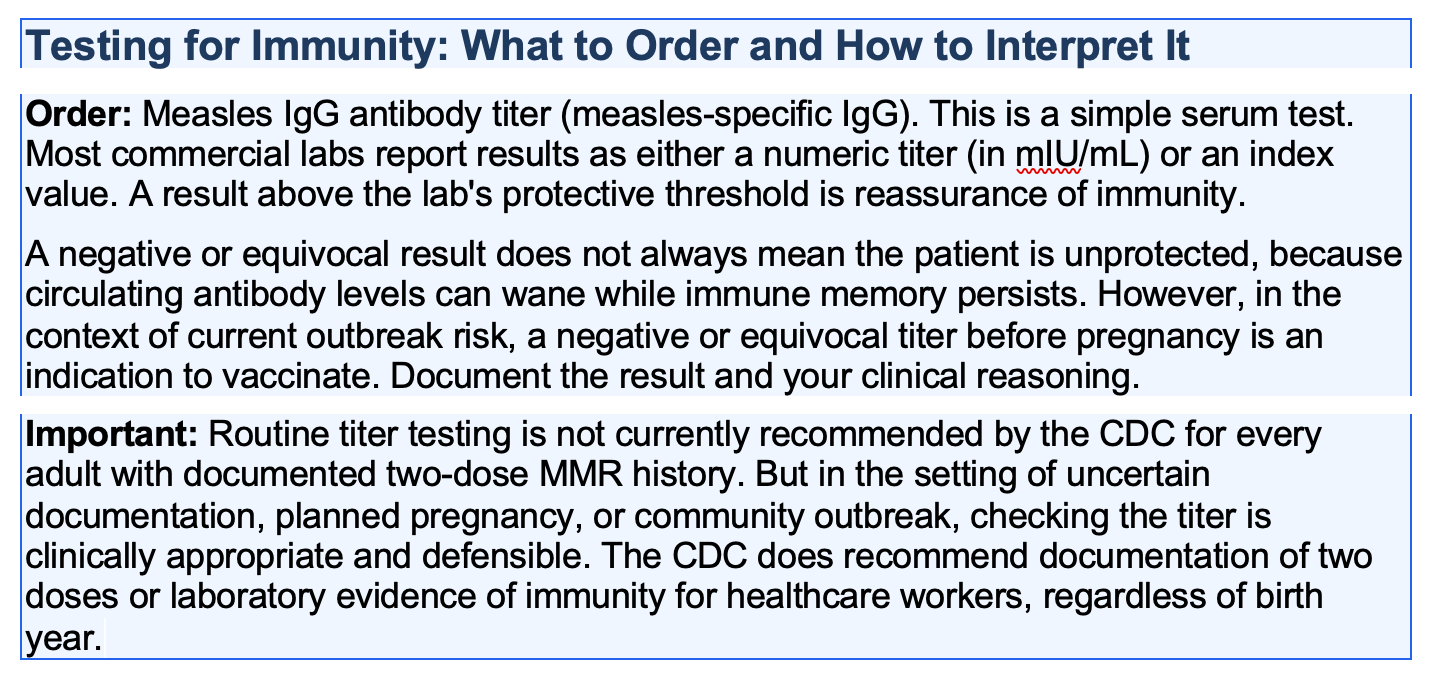

No documentation, no memory: This is the clinically common situation. In the United States, vaccination records from childhood are often lost. Do not assume. Order the titer.

Vaccination Before Pregnancy

MMR is a live attenuated vaccine. It is listed as contraindicated in pregnancy, but the clinical reality behind that label is more nuanced than most clinicians explain to patients. The contraindication is explicitly a precautionary measure, not a reflection of documented fetal harm. The WHO Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety reviewed the available literature and concluded that the contraindication of MMR-containing vaccines is “considered a purely precautionary measure,” and that inadvertent vaccination of pregnant women is not an indication for pregnancy termination. The CDC takes the same position.

The evidence behind inadvertent MMR vaccination in pregnancy is reassuring. The CDC established a Vaccine in Pregnancy registry in 1971 that followed women who received rubella-containing vaccines within three months before or after conception. By 1989, data existed on 1,221 inadvertently vaccinated pregnant women. There was no evidence of an increase in fetal abnormalities or congenital rubella syndrome. Enrollment ended because no signal emerged. A Motherisk prospective controlled study of 94 women exposed to rubella vaccine in the three months before conception or during the first trimester found no difference in pregnancy outcomes or malformation rates compared to unexposed women. A systematic review published in Vaccine in 2019 examined 42 studies spanning 1973 to 2011 and identified no case of vaccine-associated congenital rubella syndrome. MotherToBaby, which synthesizes outcomes data from at least 1,600 pregnancies in which MMR was given just before or during pregnancy, found no increased chance of birth defects.

If a patient planning pregnancy is found to be non-immune, she should receive MMR before conception. The standard recommendation is to wait 28 days after MMR vaccination before attempting pregnancy. This interval is based on theoretical precaution, not on evidence of harm. It is widely established and should be followed. But when a patient presents already pregnant and non-immune, or when inadvertent vaccination occurred before she knew she was pregnant, the data are clear: she should be counseled about the theoretical risk and reassured that the evidence does not support pregnancy termination on this basis alone. That is the CDC position, the WHO position, and the conclusion of the available registry and observational data.

After the MMR series, check a titer to confirm seroconversion before pregnancy is attempted if there is clinical uncertainty. In current outbreak conditions, this is not overcautious. It is standard of care. For patients who discover they are non-immune after conception has already occurred, vaccination must wait until after delivery. These patients should be counseled specifically: their risk from measles exposure during pregnancy is real, and they should avoid known outbreak areas and exposures. They are relying entirely on community immunity for protection during their pregnancy. At this vaccination coverage, that is a fragile guarantee.