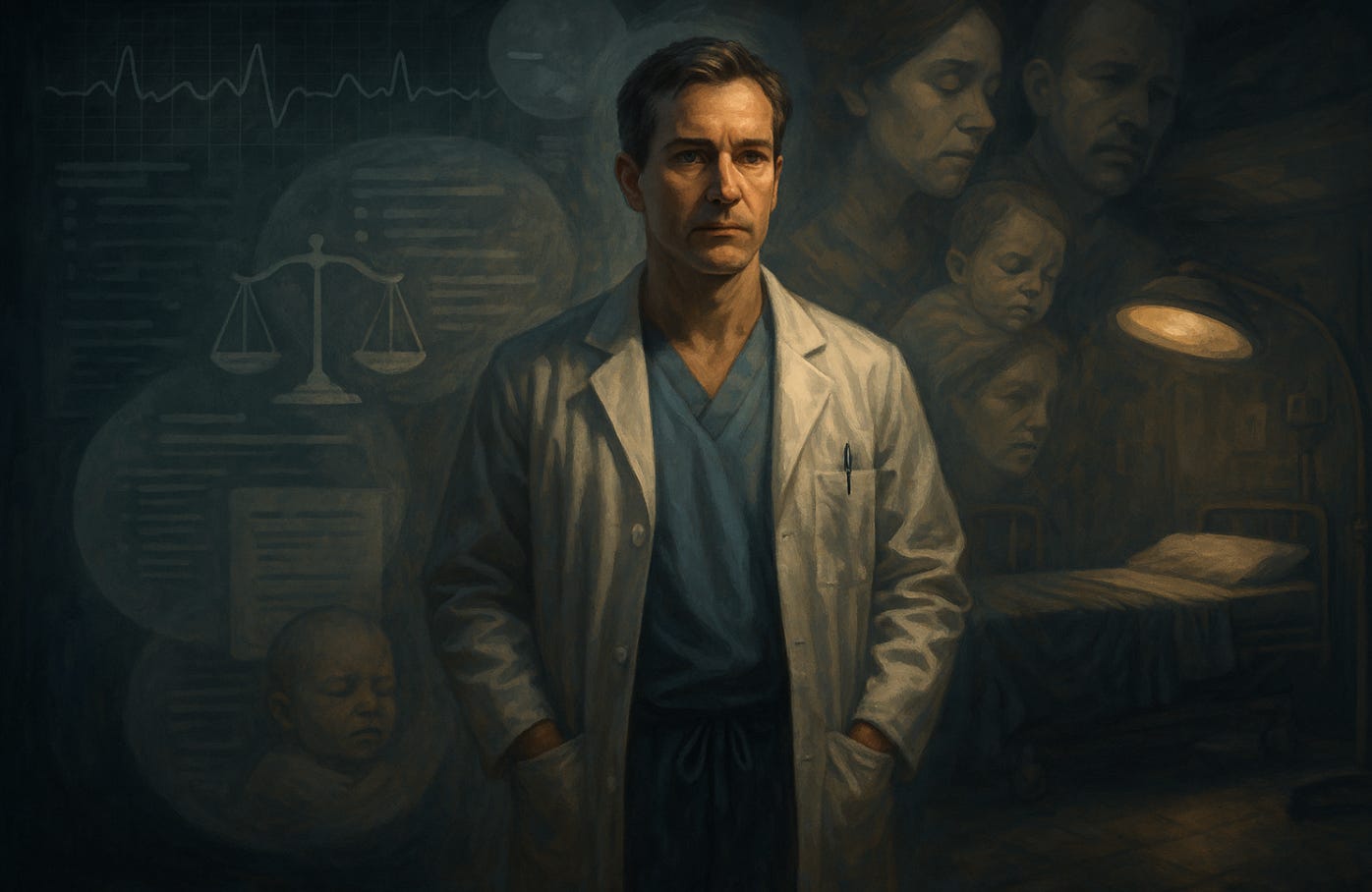

The Human Factor: Invisible Labor

The unseen cognitive and emotional work behind obstetric decision-making

I once stood in a labor room at 3 a.m., watching the fetal monitor trace slow decelerations. The patient, a first-time mother, was exhausted. Her husband asked if everything was “okay.” Nurses shifted uneasily. On the surface, the room looked calm. But inside my head, a storm was raging: Is this true fetal distress or just variable decelerations? Should I continue to wait, or is it time for a cesarean? How much risk is acceptable for the baby, and how much intervention is acceptable for the mother?

No one in that room saw the calculations, the memories of prior cases, the ethical dilemmas—all silently layered into my decision-making. This is the invisible labor of being an obstetrician.

Training for the Unseen

It takes more than a decade of training to prepare a physician to stand in that room. Four years of medical school, four years of residency, and for many of us, another three years of fellowship. That’s eleven years after college—years spent memorizing, practicing, being tested, and being humbled.

And yet, even after all that, what truly defines an obstetrician is not just the knowledge of anatomy or the skill of performing a cesarean. It is the ability to hold uncertainty, to balance autonomy with safety, to act under pressure when two lives depend on one decision.

Patients often see the outcome but not the process. They see a doctor recommending induction or cesarean, but not the thousands of hours of training and the hundreds of prior births shaping that judgment. Like a duck gliding across water, the smooth surface hides frantic paddling beneath.

Cognitive and Emotional Weight

Every decision in obstetrics carries multiple dimensions:

Medical evidence: What do studies and guidelines say?

Clinical experience: How does this compare to cases I’ve seen before?

Ethical balance: Whose risk carries more weight in this moment—mother or baby?

Emotional context: How do I explain this in a way that builds trust, not fear?

The emotional labor is often overlooked. We must be calm while our minds race, reassuring while making calculations, compassionate while holding life-and-death probabilities in our heads.

Sometimes the hardest part is not the medicine, but the communication. Saying, “I recommend a cesarean now,” carries a different weight depending on whether the patient feels respected or railroaded. Those words are never just medical; they are relational, ethical, and deeply human.

The Hidden Toll

Invisible labor also takes a toll on the physician. Decision fatigue is real. Obstetricians can make dozens of high-stakes choices in a single shift, often with little sleep. Unlike other specialties, labor does not pause at night or on weekends.

Behind every decision is the haunting awareness of what could go wrong. We remember the rare tragedies. We carry the weight of outcomes long after others have forgotten. Patients see the moment; doctors carry the memory.

What’s Overlooked

Society often undervalues this invisible work. Popular narratives about childbirth sometimes reduce obstetricians to technicians—surgeons eager for cesareans, doctors who “interfere” with natural birth. But the reality is far richer. Each intervention is the end point of a long invisible process: weighing risks, recalling literature, balancing ethics, and shouldering responsibility.

In the same way that invisible household labor—planning meals, remembering appointments—has only recently been recognized, the invisible mental and emotional labor of physicians deserves acknowledgment.

A New Kind of Help

Until now, obstetricians have carried this burden largely alone, supported only by colleagues, experience, and whatever guidelines could be recalled in the moment. But with generative AI (GAI), something new is happening.

For the first time, physicians may gain a real partner in managing the information overload. Imagine standing at the bedside and, instead of relying only on memory, having instant access to the latest evidence, outcomes data, and patient-specific guidelines—all filtered in real time.

GAI will not replace the invisible labor of empathy, ethics, or responsibility. But it can lighten the cognitive load, giving doctors the ability to focus more of their mental energy on human connection rather than on hunting for information.

Reflection

Obstetrics has always demanded invisible labor—the unseen calculations, the emotional steadiness, the years of training compressed into one moment of decision. That labor has kept mothers and babies safe, often without recognition.

The question is: as generative AI becomes a tool in our hands, will we allow it to make the invisible more visible? Will we use it to remind patients, families, and even ourselves of the immense unseen work that goes into each decision—and to finally share a bit of that burden?