Friction - Safeguarding Safety in Labor and Delivery: Preventing Errors Through Standardization and Intelligent Systems

Every ten minutes, a laboring woman or her baby is exposed to preventable harm from a system that could be smarter, safer, and more accountable.

Labor and delivery should be the safest place in any hospital. Yet, it remains one of the most error-prone environments in modern medicine.

High stakes, time-critical decisions, and fragmented communication make it fertile ground for preventable harm. Unlike other hospital units, obstetric teams manage two patients at once—the mother and her baby—often amid shifting physiology, incomplete data, and emotional intensity.

The Alarm That Changed Everything

I was sitting at the labor and delivery desk when an alarm rang from one of the rooms. The fetal heart rate had dropped abruptly into a prolonged bradycardia. Within seconds, the team mobilized for a stat cesarean. The baby was delivered quickly, pale and limp but with a strong recovery after resuscitation.

Only later, during the debrief, did we discover what had happened. A nurse had inadvertently started an oxytocin infusion, prepared for postpartum use, instead of the normal saline maintenance line. The concentration was far higher than any intrapartum protocol allowed. The error was not due to negligence but to a system failure: identical-looking bags, inconsistent labeling, and no second check at the bedside.

Our first improvements were changing the size of the oxytocin bags, standardizing concentrations and color labeling the bag.

It was a narrow escape. The incident could easily have resulted in catastrophic hypoxia. It became a turning point for our unit, a visceral reminder that the line between routine and emergency can be measured in milliliters and minutes.

The Hidden Risk in Routine Care

Every obstetrician knows that small deviations can cause devastating outcomes: an oxytocin rate miscalculated, a misread fetal tracing, or a missed allergy. A 2025 review in Expert Opinion on Drug Safety found that in neonatal units, most preventable harm occurred not during prescribing but at the administration stage. The same pattern exists in obstetrics. The majority of medication and monitoring errors in L&D occur at the point of care, when time pressure, human fatigue, and inconsistent processes collide.

Common error categories include:

Incorrect medication administration – wrong dose or timing of oxytocin, magnesium sulfate, or epidural anesthetics.

Failure of communication – omitted handoffs between shifts or unclear documentation of induction parameters.

Equipment misuse – misprogrammed pumps or uncalibrated fetal monitors.

Delayed escalation – hesitation to call for senior review during fetal heart rate abnormalities or postpartum hemorrhage.

Each of these errors is often preventable, but only when systems are designed to anticipate them.

Standardization Saves Lives

Labor and delivery lacks the level of procedural standardization that has transformed anesthesia and neonatal intensive care. Checklists, double-verification of high-risk medications, and timeouts for induction or cesarean protocols remain inconsistently applied.

For example, oxytocin, a high-alert drug with a narrow therapeutic window, is frequently prepared or titrated differently across hospitals, even across shifts. Inconsistent documentation of indication, concentration, and infusion rate multiplies the risk.

Adopting standardized tools such as:

Pre-mixed, labeled oxytocin bags

Electronic order sets with built-in dose limits and alerts

Barcode medication administration

has been shown in other specialties to cut error rates by half. Yet, L&D units lag behind in implementation.Requiring the attending to document the indication for the oxytocin. That part was actually among the most contentious requirements. Many attendings refused this requirement as they believed it was their right toorder a medication without being asked why.

Requiring an informed consent from the patient. Again, contentious.

The Human Factor

Technology alone cannot fix unsafe culture. In obstetrics, the “hidden hierarchy” often silences nurses or junior physicians who sense that something is wrong. Creating a just culture—one that balances accountability with learning—is the cornerstone of real safety. Staff must feel psychologically safe to report near-misses without fear of punishment.

Simulation-based training offers a particularly effective solution. Rehearsing rare but catastrophic events like shoulder dystocia, eclampsia, or uterine rupture reduces both time to intervention and communication errors. Evidence from multiple institutions, including Cornell and Northwell, shows that requiring both residents and attending physicians to complete simulation every two years dramatically reduces litigation and response delays.

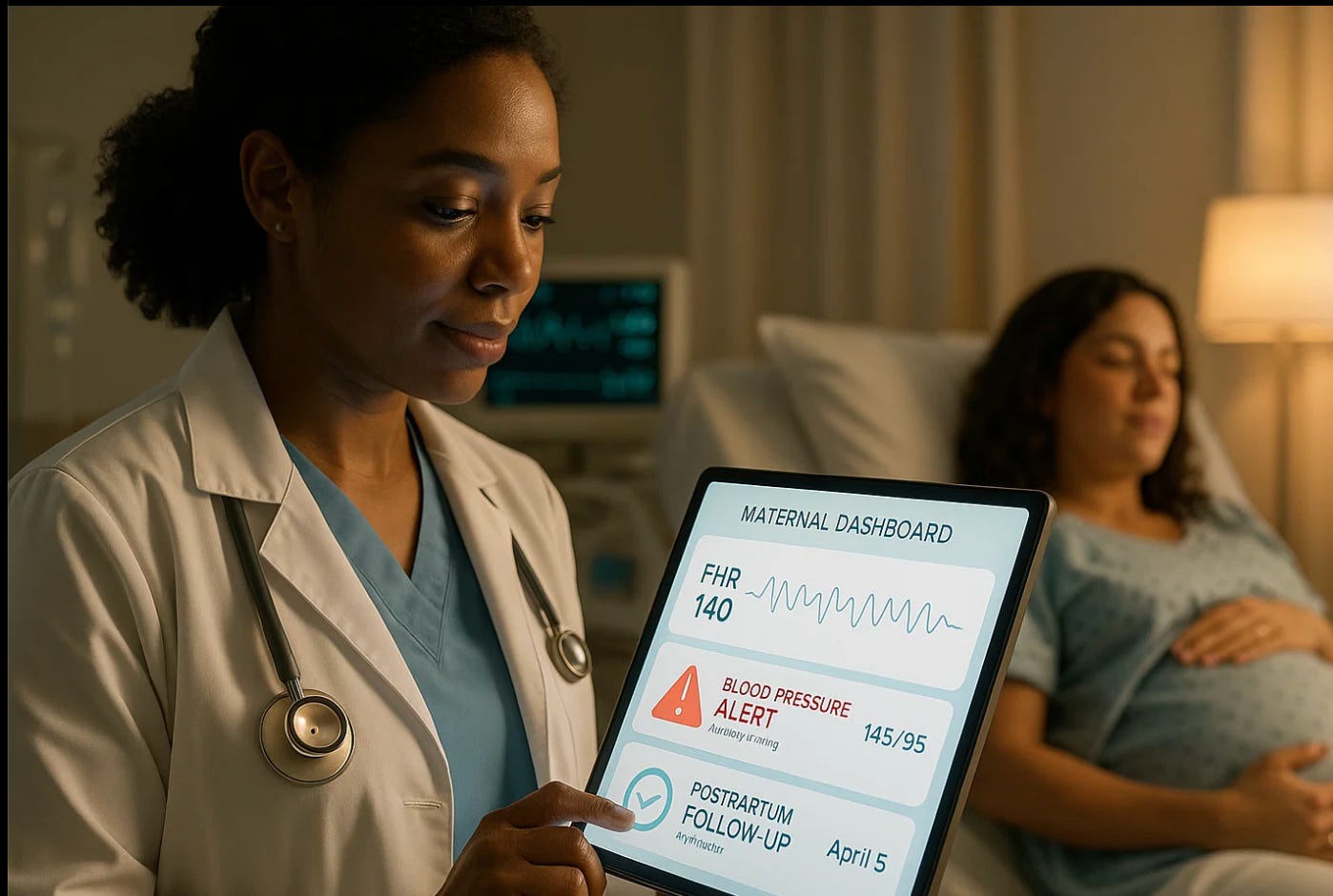

Intelligent Systems for a Smarter Labor Floor

Artificial intelligence is now capable of detecting early warning signs long before clinicians notice them. Just as predictive models identify sepsis in the ICU, labor algorithms can flag concerning trends in fetal heart tracings, oxytocin overuse, or postpartum hemorrhage risk.

When used ethically and transparently, these systems enhance—not replace—clinical judgment. Yet, as studies like Martos et al. in JAMA Network Open (2025) showed for AI translation, accuracy depends on language, context, and validation. Similarly, unvalidated algorithms in labor monitoring can amplify disparities rather than reduce them. Hospitals must ensure algorithm transparency, continuous bias monitoring, and clinician oversight of every alert.

From Data to Prevention

Comprehensive, structured documentation is the foundation of safety improvement. Without accurate data, comparative effectiveness research, quality audits, and regulatory oversight fail. As in neonatal pharmacovigilance, “you cannot improve what you do not document.” Labor units must implement:

Electronic partograms and real-time data dashboards

Automated capture of infusion rates, tracings, and decisions

Post-event debrief tools linked to learning databases

When errors or near-misses occur, they should be logged as opportunities for learning, not blame. Consistent use of international frameworks—like the WHO’s International Classification for Patient Safety—enables benchmarking across hospitals and countries.

The Ethical Imperative

Improving safety in labor and delivery is not merely a technical challenge. It is an ethical duty. A single preventable maternal or neonatal injury undermines trust in the entire profession. Obstetricians and nurses must lead—not wait—for system redesign. Adopting standardized protocols, encouraging open reporting, and integrating intelligent surveillance are moral obligations rooted in respect for patient autonomy and nonmaleficence.

The next era of obstetric safety will depend not just on better equipment but on better thinking systems: teams that learn, adapt, and use AI responsibly to protect mothers and babies.

Reflection

Every L&D unit should ask itself one question: If this were my own daughter giving birth here tonight, would our safety systems be enough? The answer must never depend on luck, experience, or which staff are on call. It must depend on a culture where vigilance, data integrity, and ethical accountability converge—ensuring that every dose, every decision, and every delivery is as safe as it can possibly be.