“First, Do No Harm” — The Medical Phrase That Isn’t What You Think

Why medicine’s most famous motto is neither ancient nor particularly helpful. Especially in Women's Health.

You’ve heard it a thousand times. Someone debates a medical treatment and drops the ultimate mic: “Well, the Hippocratic Oath says ‘First, do no harm.’”

Except it doesn’t.

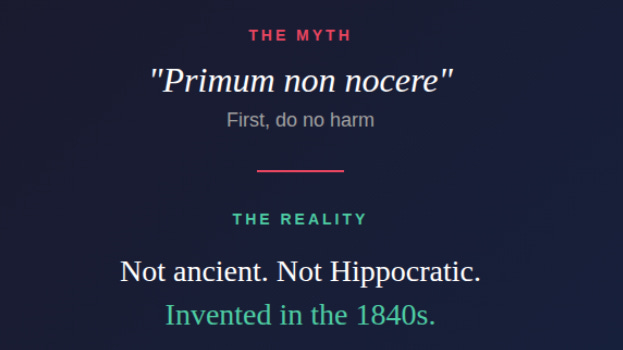

And that Latin phrase everyone loves to quote — *primum non nocere* — isn’t Roman wisdom. It’s not even ancient. It’s a 19th-century invention that has been doing medicine a disservice for over 150 years.

The Latin Problem

Here’s the first clue that something is off: Hippocrates was Greek. He wrote in Greek. So why would his most famous teaching be in Latin?

The answer is simple: it’s not his teaching.

The phrase *primum non nocere* first appeared in print around the 1840s and 1850s. Medical historians have traced it to Auguste François Chomel, a French physician who apparently used it in his teaching. An American physician named Worthington Hooker popularized it in his 1847 book *Physician and Patient*. Thomas Inman used it in 1860 and wrongly credited it to Thomas Sydenham, a 17th-century English physician.

Within decades, doctors had attributed it to Hippocrates — despite the obvious problem of a Greek man supposedly coining a Latin phrase about 400 years before Latin became the language of medicine.

What the Hippocratic Oath Actually Says

If you read the actual Hippocratic Oath — the original Greek version — you won’t find “First, do no harm” anywhere.

What you will find is: “I will use treatment to help the sick according to my ability and judgment, but never with a view to injury and wrong-doing.”

See the difference? The emphasis is on *helping* first, with harm avoidance as a qualifier. The original is positive and active. The made-up motto is negative and passive.

Even more telling is what the Hippocratic Corpus (the collection of texts attributed to Hippocrates and his followers) says in a work called *Epidemics*: “The physician must have two special objects in view with regard to disease, namely, to do good or to do no harm.”

Again: do good comes *first*. Not doing harm is the backup plan when you can’t help.

Why This Matters in ObGyn

Now let’s bring this to where I work every day: labor and delivery.

If doctors truly practiced “first, do no harm” as written, we would do almost nothing.

Think about it:

- Cesarean delivery involves cutting through the abdomen. That’s harm. But it saves lives when vaginal birth is unsafe.

- Epidural anesthesia requires placing a needle near the spinal cord. That’s harm. But it provides pain relief and sometimes allows vaginal delivery when a mother couldn’t otherwise cope.

- Induction of labor uses medications that carry risks. That’s harm. But continuing a pregnancy past its safe point carries bigger risks.

- Even a simple blood draw causes pain and can cause bruising. That’s harm. But we need the information to provide safe care.

If “do no harm” were truly the first rule, pregnant women would receive no prenatal care, no monitoring, no interventions — and many more would die.

The Modern Framework: Benefits Must Outweigh Risks

Modern patient safety takes a completely different approach. The question isn’t “Does this cause any harm?” The question is “Do the benefits outweigh the risks?”

This is called risk-benefit analysis, and it’s the actual foundation of medical ethics today.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists puts informed consent and shared decision-making at the center of ethical care. The goal isn’t to avoid all possible harm. It’s to:

1. Give patients accurate information about risks *and* benefits

2. Help patients understand their options

3. Support patients in making decisions that align with their values

4. Document the conversation

Almost every medical intervention carries some risk. The ethical question isn’t whether risk exists — it’s whether the patient understands that risk and agrees that the potential benefit is worth it.

The Home Birth Example: When “Less Intervention” Isn’t Safer

This flawed logic plays out dramatically in debates about home birth.

Some home birth advocates argue that birth is “safer” at home because there are fewer interventions. Fewer IVs. Fewer monitors. Fewer cesareans. By the “first, do no harm” logic, less intervention should mean less harm.

But this confuses the absence of intervention with the absence of risk.

U.S. data tells a different story. A study using CDC vital statistics from 2010-2017 found that neonatal mortality for hospital births attended by midwives was 3.27 per 10,000 live births. For planned home births? It was 13.66 per 10,000 — more than four times higher.

A widely cited meta-analysis in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology found that while home births had fewer interventions, they also had triple the neonatal mortality rate compared to hospital births.

ACOG’s position is clear: planned home birth is associated with more than twice the risk of perinatal death and three times the risk of neonatal seizures or serious neurologic problems compared to hospital birth.

Why? Because interventions exist for a reason. When a baby’s heart rate drops dangerously, you need the ability to perform an emergency cesarean in minutes — not the ability to transfer to a hospital 20 or 30 minutes away. When a mother hemorrhages, you need blood products and surgical capability immediately available.

The availability of interventions is precisely what makes hospital birth safer. Fewer interventions at home doesn’t mean fewer bad outcomes. It means fewer options when something goes wrong.

This is “first, do no harm” thinking at its most dangerous: treating the presence of medical capability as the threat, rather than the emergency it exists to address.

What “Primum Non Nocere” Gets Wrong

The made-up motto encourages passivity. It suggests that the safest choice is always the least active one. It implies that not acting is neutral.

But in medicine, inaction is itself a choice with consequences.

When a patient is in labor with a baby showing signs of distress, not performing a cesarean is not a “neutral” choice. It’s a choice that carries its own risks.

When a pregnant woman has severe high blood pressure, not inducing labor is not “doing no harm.” It’s accepting the risk of stroke, seizure, or death.

Medicine requires doctors to weigh competing harms and benefits, not to pretend that one option is harm-free.

What We Should Say Instead

If we need a guiding principle for medical ethics, the original Hippocratic idea is actually quite good: help the patient while avoiding intentional harm.

Even better is the modern framework:

- Be honest about all the options

- Be clear about risks and benefits

- Support the patient’s informed choice

- Take action when benefits outweigh risks

This isn’t as catchy as a Latin motto, but it’s far more useful.

The Bottom Line

“First, do no harm” sounds wise. It sounds ancient. It sounds like bedrock medical ethics.

But it’s none of those things.

It’s a 19th-century invention, wrongly attributed to the Greeks, that has been used to justify inaction when action was needed.

Real medical ethics isn’t about avoiding all possible harm. It’s about honest conversations, weighing risks against benefits, and making decisions together with patients.

The next time someone invokes *primum non nocere* in a medical debate, you have my permission to point out that it’s not ancient, it’s not Hippocratic, and it’s not actually how good medicine works.

This was a FREE post. If you like my writings, please subscribe:

The linguistic sleight-of-hand here is fascinating. A Greek physician supposedly coins a Latin maxim 400 years before Latin medical terminology even existed. The home birth stat comparison really drives home how "fewer interventions" gets confused with "less risk" when interventions exist precisely to handle emergenceis. Risk-benefit analysis over fake ancient wisdom is way more honest.