Birth Defects: A Public Health Challenge and a Shared Opportunity for Prevention

There is much that can be done by both women and men to prevent birth defects

Defining the problem

Birth defects, also called congenital anomalies, are structural or functional abnormalities that occur during embryonic or fetal development. They include conditions such as congenital heart defects, neural tube defects, and orofacial clefts, which together represent some of the most common and serious outcomes in perinatal medicine. In the United States, about 1 in 33 babies (3%) is born with a major birth defect, making them a leading cause of infant mortality and long-term disability.

Although many birth defects are genetic or chromosomal in origin, a significant portion are influenced by health behaviors and environmental exposures. Research suggests that up to 30% of birth defects may be preventable. This places prevention squarely in the realm of shared responsibility—something that involves both women and men well before conception.

Modifiable risks: what couples can change together

Several risk factors have been clearly linked to birth defects and adverse pregnancy outcomes. These risks apply not just to the mother but often to the father as well, either through direct biological influence on sperm quality and DNA or through shared household environments and behaviors.

Folate and vitamin B12 deficiency: Folate is essential for neural tube closure, and deficiencies raise the risk of neural tube defects and possibly congenital heart defects. While women are advised to take supplements (≥400 mcg folic acid daily), men also benefit from adequate folate intake, which supports sperm quality and reduces DNA damage.

Obesity and diabetes: Maternal obesity and pre-gestational diabetes increase the risk of congenital heart defects, neural tube defects, and stillbirth. Paternal obesity and diabetes are associated with impaired sperm quality, altered epigenetic programming, and higher risk of miscarriage. Both partners adopting healthy weight management, balanced nutrition, and physical activity can reduce risks.

Tobacco use: Maternal smoking is linked to orofacial clefts, growth restriction, and placental complications. Paternal smoking lowers sperm quality and exposes partners to secondhand smoke, which independently raises risks of low birth weight and possibly birth defects. Quitting together is more effective than one partner quitting alone.

Alcohol use: Alcohol is one of the most potent teratogens, causing fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs). There is no safe level of alcohol during pregnancy. For men, heavy drinking impairs sperm DNA integrity and increases oxidative stress. For couples planning pregnancy, abstaining together offers the strongest prevention strategy.

Food insecurity: Limited access to healthy foods undermines nutritional status for both partners. It contributes to folate and vitamin deficiencies, unhealthy weight, and reliance on processed foods that worsen metabolic risk. Addressing this requires both family-level strategies and policy-level solutions.

Taken together, these risks remind us that birth defect prevention begins with the couple, not just the woman.

What the new study shows

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007–2020 examined more than 5,300 nonpregnant, nonlactating U.S. women of reproductive age. The findings highlight how widespread modifiable risks remain:

66% had at least one preventable risk factor, and more than 10% had three or more.

Obesity increased from 28.9% to 37.9%.

Diabetes nearly doubled, rising from 3.2% to 6.0%; prediabetes affected more than one-third.

Smoking exposure decreased from 21.2% to 16.8%, but still involved nearly one in five.

Very low food security worsened, from 5.0% to 7.6%.

Folate deficiency persisted: nearly 20% had red blood cell folate levels below the protective threshold, and almost 80% consumed less than the recommended daily intake.

Although alcohol use was not included in this dataset, other surveys show that about 10% of pregnant women report alcohol consumption and 3–5% report binge drinking. Given its causal role in birth defects, alcohol must be considered alongside the risks highlighted by NHANES.

Why shared prevention matters

Birth defects often develop in the earliest weeks of pregnancy—before many people know they are expecting. That makes preconception health the most effective window for prevention. Both women and men can contribute:

A woman entering pregnancy with good nutrition, optimal folate status, controlled blood sugar, and without alcohol or tobacco exposure sharply reduces risk.

A man entering conception with healthy weight, good sperm quality, and no smoking or alcohol improves fertility, reduces DNA damage in sperm, and lowers miscarriage risk.

Together, couples who share lifestyle changes—improving diet, exercising, quitting alcohol and smoking—are more likely to sustain those behaviors and achieve healthier outcomes.

The risks are interconnected. For example, if the man smokes, his partner may be exposed to secondhand smoke. If both partners consume alcohol, abstaining together is far easier than one person doing it alone. And if a family struggles with food insecurity, it affects the health of everyone in the household, not just the pregnant woman.

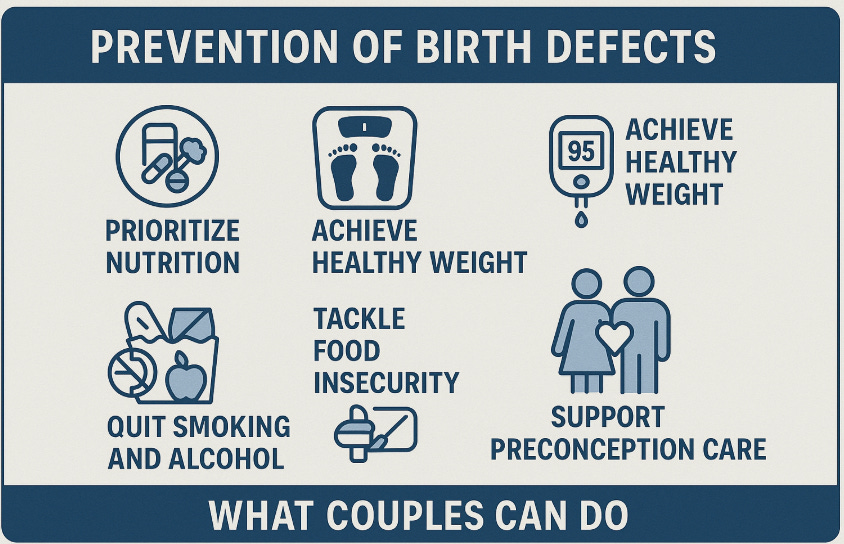

What couples can do

Start before pregnancy is confirmed: Because defects develop early, both partners should optimize health when pregnancy is possible or planned.

Prioritize nutrition: Women should take folic acid supplements starting at least 3 months before conception, but preferable even before. Men also benefit from folate and B12 for sperm health. A diet rich in vegetables, fruits, lean proteins, and fortified grains supports both partners.

Achieve healthy weight: Even modest weight loss improves metabolic health. Couples can set shared goals for physical activity and cooking healthier meals at home.

Address diabetes and prediabetes: Screening and early management for both men and women improve outcomes.

Quit smoking and alcohol together: Shared commitment makes cessation more successful. For alcohol, abstinence before and during pregnancy is the safest approach.

Tackle food insecurity: Using available community resources, food assistance programs, and policy advocacy helps ensure both partners enter pregnancy nourished. Food insecurity is not only about the absence of food but also about the quality of food available. Many families rely on fast food because it feels quick and accessible, yet meal-for-meal, fast food is often more expensive than preparing balanced meals at home—especially when considering nutrient value. A single fast food meal for two can easily cost more than buying ingredients for a simple home-cooked dinner that yields leftovers. The problem is not just price but convenience, time pressures, and lack of food preparation resources. Public health solutions must therefore go beyond supplementation programs to include nutrition education, incentives for healthy eating, and structural supports (such as subsidized produce, cooking classes, or policies that make healthy choices the easier and cheaper option). By addressing these barriers, couples can move away from reliance on calorie-dense but nutrient-poor foods and toward diets that genuinely support reproductive and long-term health.

Support preconception care: Men should accompany women to preconception visits, reinforcing the message that this is a joint responsibility. Preconception care refers to medical and lifestyle interventions provided before pregnancy occurs, aimed at identifying and modifying risk factors that could affect fertility, maternal health, or fetal development. These visits typically include counseling on nutrition and supplements (such as folic acid), screening and management of chronic conditions like diabetes or hypertension, vaccinations, and guidance on avoiding harmful exposures such as smoking and alcohol. When both partners are present, it strengthens adherence to recommendations and ensures that men also receive counseling on their own health—such as managing weight, reducing alcohol, and improving sperm quality. Preconception care, therefore, is not just a women’s appointment; it is a couple’s opportunity to create the healthiest possible foundation for conception and pregnancy.

From risk to action

Effective prevention requires both individual and systemic action. Couples can make lifestyle changes together, but they need the support of broader systems: access to affordable healthy foods, insurance coverage for preconception visits, community nutrition programs, and public campaigns against alcohol and tobacco use.

Framing prevention as a partnership also changes the narrative: it’s not just about what women must do to protect a pregnancy, but about what couples can do together to create the healthiest possible environment for a future child.

Conclusion: prevention is within reach

The NHANES data highlight a sobering reality: two-thirds of U.S. women of reproductive age carry at least one preventable risk for birth defects. Combined with what we know about paternal health, it is clear that prevention must be viewed as a couple’s responsibility.

With better nutrition, healthier weight, improved diabetes control, elimination of alcohol and tobacco, and stronger social supports, we could prevent a substantial fraction of birth defects—perhaps up to 30%. Not every anomaly can be avoided, but many are influenced by conditions that couples can change together.

Birth defects remain one of the most serious yet under-recognized public health challenges. By reframing prevention as a shared responsibility of both women and men, we have an opportunity to improve maternal and infant health, strengthen families, and create healthier future generations. The science is clear: prevention is possible, but only if we act together, and act early.