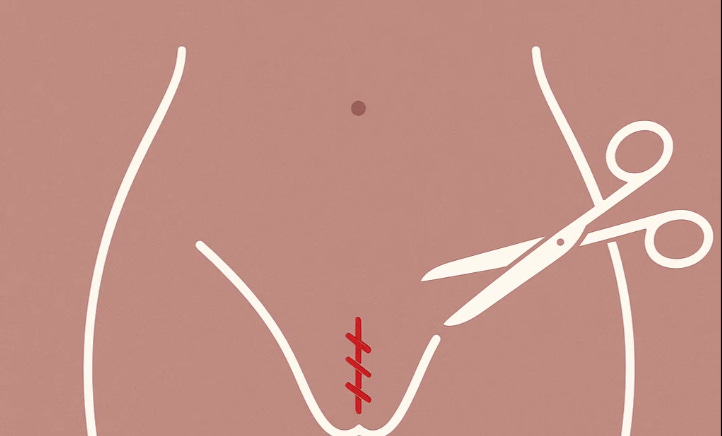

Beyond the Myths: Real Science in Women's Health - Episiotomy Prevents Severe Tears? Think Again.

Rejecting routine episiotomy doesn’t mean we should never perform it. There are situations where an incision can truly help protect mother and baby.

I still remember the early years of my training.

When a baby’s head began to crown, it was almost automatic: scissors in hand, we cut an episiotomy. The reasoning was simple and, at the time, widely accepted—better a clean surgical cut than a ragged tear. We were taught that this quick snip would prevent severe perineal trauma, protect the pelvic floor, and ensure a smoother recovery.

But medicine, like life, has a way of humbling us.

What Exactly Is an Episiotomy?

An episiotomy is a surgical incision made in the perineum—the tissue between the vagina and the anus—during childbirth. The idea was that by enlarging the vaginal opening in a controlled way, doctors could prevent spontaneous tears that might extend deeply into muscles or the anal sphincter. For decades, this was routine practice in labor wards across the world.

To many of us, it felt protective, even merciful. Parents were rarely asked; the procedure was “standard.” But standard is not always the same as safe.

The Research That Changed Everything

In the 1980s and 1990s, researchers finally began asking the obvious question: did routine episiotomy actually prevent severe trauma? The answer was a resounding no.

Large studies showed that routine episiotomy didn’t reduce third- or fourth-degree tears (the most severe kinds, extending into the anal sphincter or rectum). In fact, it sometimes increased the risk, since the incision itself could extend unpredictably into the very areas we hoped to protect. Women also faced longer healing times, more pain, and higher rates of infection.

The World Health Organization, ACOG, and other professional bodies now recommend a restrictive use of episiotomy, performed only when clearly indicated.

When Is Episiotomy Still the Right Choice?

Rejecting routine episiotomy doesn’t mean we should never perform it. There are situations where an incision can truly help protect mother and baby. These include:

Fetal distress: when the baby needs to be delivered quickly and safely.

Operative vaginal delivery: when forceps or a vacuum are required, and more room is needed.

Shoulder dystocia: if extra space can aid in maneuvers to free a stuck shoulder.

Rigid perineum: in rare cases, when tissue simply will not stretch despite efforts to support it.

The difference today is that episiotomy is no longer reflexive. It is a deliberate decision, based on clear clinical need, not habit.

Why Did This Myth Last So Long?

Medicine often lags behind evidence. Once a procedure becomes ingrained, it takes years—sometimes decades—to unwind. Episiotomy was part of a culture of control in childbirth, where doctors, not mothers, determined what was “best.” It took carefully designed trials, persistent researchers, and courageous patients to shift the paradigm.

It’s also a reminder of how easily plausibility can masquerade as truth. A clean cut looks tidier than a jagged tear, so it felt safer. But the body isn’t a piece of cloth; living tissue heals differently.

What We’ve Learned

Today, routine episiotomy is recognized as an outdated practice. Rates have dropped significantly in many hospitals, though in some parts of the world, old habits remain stubborn.

What have we gained from moving away from routine cuts?

Less unnecessary trauma: Most births do not require an incision.

Better healing: Natural tears are usually smaller and heal more effectively.

Respect for autonomy: Parents are now more often asked, informed, and included in decisions.

This is one of the quiet revolutions in obstetrics—where evidence replaced tradition, and women’s bodies were finally trusted to do what they were built to do.

Beyond the Scissors

The episiotomy story isn’t just about one procedure. It’s about the larger lesson: in medicine, “routine” should never be confused with “necessary.” Every cut, every intervention, every “standard practice” must stand up to evidence.

For patients, it’s a call to ask: Is this truly needed, or is it just what’s always been done?

For clinicians, it’s a reminder to stay humble. We may feel certain today, but tomorrow’s research may prove otherwise.

Reflection

Episiotomy went from unquestioned ritual to a cautionary tale in just one generation. How many other “next-level” myths still shape what we do in the delivery room today? And how do we balance tradition, urgency, and the humility to admit when the evidence says: less is more?