Beyond “Just Talk to Them”: Why Communication Alone Won’t Solve Obstetric Litigation

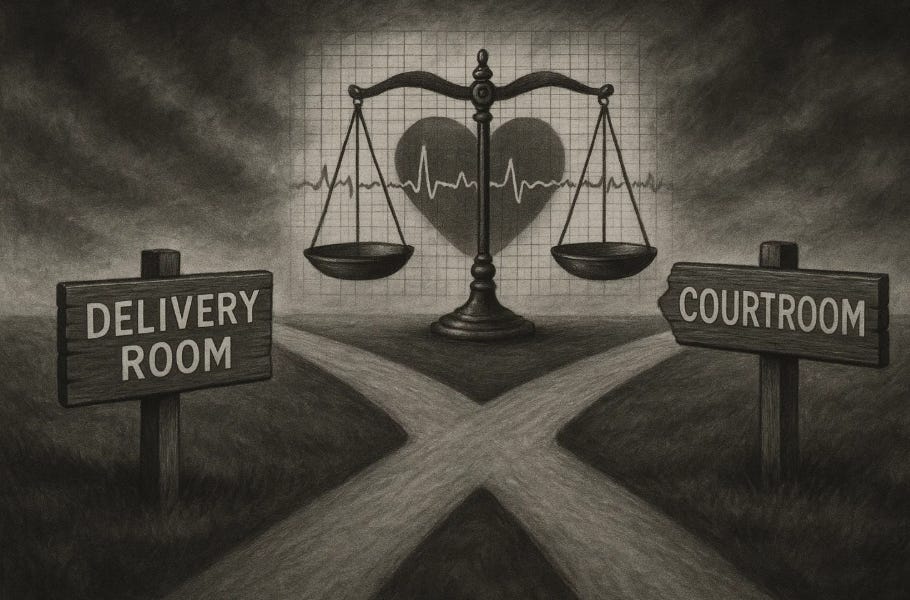

The Safety Ledger: Every lawsuit starts with harm and hinges on two questions: Did care meet the standard, and did any deviation cause the outcome?

In American tort law, the elements for a cause of action such as negligence follow a familiar framework: duty, breach, causation, and damages. To prevail, a plaintiff must prove all four.

Duty: The defendant owed a legal duty of care to act reasonably under the circumstances. For example, physicians owe their patients competent, evidence-based medical care.

Breach: The defendant failed to meet that standard—through action or omission.

Causation: The breach directly caused the injury. In other words, the harm would not have occurred but for the alleged failure, and the injury was a foreseeable result.

Damages: The plaintiff sustained measurable harm—physical, emotional, or financial—stemming from that breach.

Without all four, there is no legal case. This framework is critical to remember in obstetric litigation because it distinguishes tragedy from tort. Every lawsuit begins with harm, but not every harm reflects a breach of duty or a failure of care.

Litigation doesn’t start with bad communication. It starts with harm, and hinges on whether care met the standard—and whether anything different could have changed the outcome.

Duty and the Standard of Care

In medicine, duty is clear: clinicians and hospitals must provide care consistent with what a reasonably competent peer would do under similar circumstances. The standard of care doesn’t demand perfection. It allows for variation in clinical judgment, since obstetrics is filled with uncertainty. Two physicians might make different decisions about labor management and both still meet the standard, provided their reasoning and actions reflect accepted medical practice.

A breach occurs only when a provider’s actions fall outside what informed, careful peers would have done. It is not enough that the outcome was poor or that hindsight reveals alternate paths. Medicine is probabilistic, not predictive.

Causation: The Hardest Link to Prove

Even if a breach is established, plaintiffs must prove causation—that the deviation led directly to harm. In obstetrics, this is rarely straightforward. Was the baby’s cerebral palsy caused by a 15-minute surgical delay, or by an unpreventable cord accident that occurred before arrival? Would an earlier cesarean have changed the outcome, or was the damage already done?

These are not rhetorical questions—they are the crux of almost every case. Establishing causation requires credible medical evidence, expert testimony, and the ability to link an act or omission to an outcome with reasonable probability. The “but for” standard—but for this act, the injury would not have occurred—is easy to say and difficult to prove in medicine, where multiple factors interact in unpredictable ways.

Damages: The Human Cost

When a baby is injured or a mother dies, the damages are profound—emotional, physical, and financial. Families face years of therapy, lost income, and lifelong caregiving. The law seeks to compensate those losses, but litigation is a crude instrument for doing so. It often takes years and deepens grief on both sides.

This is where the myth of “just communicate better” enters. Because communication failures clearly worsen distress, it’s tempting to believe that improved empathy could prevent lawsuits altogether. But no amount of warmth, honesty, or apology can reverse neurological injury or cover the costs of lifelong care. Communication can mitigate anger—it cannot erase causation or damages.

The Comfortable Myth

In many hospital risk meetings, one hears, “Most lawsuits aren’t about medical mistakes—they’re about poor communication.” It’s half true.

Communication failures often amplify litigation risk, but they rarely create it. Families may start seeking answers, not lawyers.

Yet when answers don’t come—or when explanations feel evasive—trust collapses, and the legal process becomes the only remaining path to information and security.

The Questions That Deepen Over Time

Week 1: Will my baby be okay?

Month 1: What happened?

Month 6: Could this have been prevented?

Year 1: Was someone responsible?

Year 2: How will we afford lifelong care?

The first two can be met with compassion. The last three require causation analysis, transparency, and practical support. Without them, communication feels hollow.

What Real Reform Requires

If we want to reduce obstetric litigation, we must address each pillar of negligence, not just the communication gap:

Duty: Maintain and teach clear, evidence-based standards of obstetric care.

Breach: Encourage system-wide learning to prevent repeated errors, not blame. And if an error happens, as they often due, create a system that prevents that error from harming the patient.

Causation: Establish expert peer review systems that can explain outcomes credibly to families.

Damages: Create predictable compensation programs, such as no-fault birth injury funds, that separate financial help from fault-finding.

Training clinicians to “talk better” is a beginning but not enough. They need institutional support to analyze causation honestly and discuss uncertainty without fear. Communication should be the final link in a chain of accountability, not the substitute for it.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Families who litigate are not malicious, and clinicians who are sued are not reckless. Both are trapped in a system that conflates tragedy with negligence and forces grief into legal language. Better communication matters—but only when grounded in truth, transparency, and a framework that recognizes the difference between medical imperfection and breach of duty.

Until medicine develops fairer ways to explain, compensate, and learn from adverse outcomes, obstetricians will keep practicing in the shadow of courtrooms, regardless of how gently they speak.

Reflection / Closing:

Empathy can soothe, but injury and causation decide. To rebuild trust, we must align communication with accountability, compassion with evidence, and apology with action. And first and foremost build systems that help us prevent errors, and if errors occur (and they will) prevent them from hurting patients.