Antibiotics in Pregnancy: Life-Saving When Needed, Harmful When Not

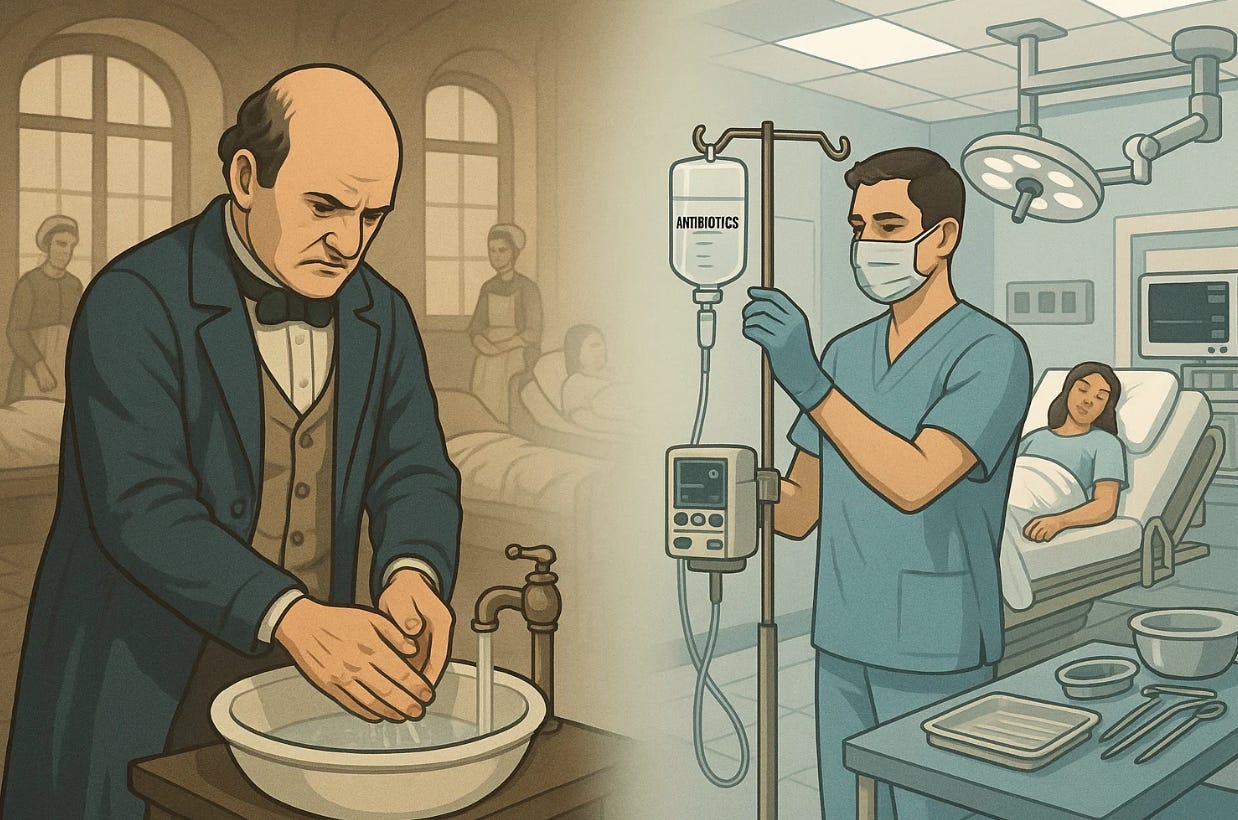

From Semmelweis to stewardship: why infection prevention still defines safe maternity care. The Safety Ledger — Notes on accountability, error, and what it really takes to keep patients safe.

Antibiotics once conquered maternal infection. Today, their overuse risks undoing that victory. True safety in obstetrics means knowing when and when not to prescribe.

It’s easy to forget that a century ago, childbirth was often deadly. Before antibiotics and antiseptic technique, infection was the leading cause of maternal death. In the mid-1800s, Ignaz Semmelweis, a Hungarian physician, observed that women delivered by doctors who came straight from autopsies were dying of “childbed fever” at far higher rates than those delivered by midwives. His simple intervention—handwashing with chlorinated lime—cut maternal mortality dramatically. Yet his colleagues mocked and dismissed him. He died in an asylum before his ideas were accepted.

Only later, with the discovery of penicillin in 1928 by Alexander Fleming and its widespread use during World War II, did infection rates in obstetrics fall sharply. Antibiotics transformed medicine. Sepsis, once the number one killer of mothers, dropped to near the bottom of the list. But with this triumph came a new danger: overuse. The same drugs that once saved lives are now breeding resistant bacteria and disturbing the microbiome of mothers and newborns alike.

What Are Antibiotics?

Antibiotics are medicines that fight bacteria—the germs that cause infections. They don’t work against viruses like the flu or a cold. When bacteria enter the body, they can grow and make toxins that make us sick. Antibiotics stop bacteria in one of two main ways: some kill the bacteria directly by breaking their cell walls, while others stop the bacteria from multiplying, giving the immune system time to finish the job. Each antibiotic works differently, and not all antibiotics treat every kind of infection.

The most common antibiotics used in pregnancy are penicillins (like amoxicillin and ampicillin), which are safe and effective against many common bacteria. Cephalosporins (like cephalexin or cefazolin) are close cousins to penicillin and are often used for urinary tract infections or before a cesarean delivery. Nitrofurantoin is often prescribed for bladder infections early in pregnancy but usually avoided close to delivery. Macrolides (like azithromycin and erythromycin) are used for certain respiratory or sexually transmitted infections. Some antibiotics—such as tetracyclines or fluoroquinolones—are avoided during pregnancy because they can affect the baby’s bones or teeth.

Used correctly, antibiotics can save both mother and baby from serious harm. Used when they’re not needed, they can cause side effects, allergic reactions, and lead to resistant bacteria that are harder to treat in the future.

When Antibiotics Save Lives

In obstetrics, antibiotics remain essential. According to ACOG and CDC guidelines, their use in pregnancy is indicated in specific, well-defined situations:

Group B Streptococcus (GBS) prophylaxis: Penicillin or ampicillin is given during labor to women who test positive, preventing newborn infection and sepsis.

Preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM): Broad-spectrum antibiotics can delay delivery and reduce neonatal infection.

Chorioamnionitis (intraamniotic infection): Immediate intravenous antibiotics are critical for both maternal and fetal survival.

Cesarean delivery prophylaxis: A single preoperative dose of cefazolin (with or without azithromycin in certain cases) reduces surgical site and endometritis risk.

Urinary tract infections and pyelonephritis: Prompt antibiotic treatment is essential because infection can trigger preterm labor or sepsis.

In these scenarios, antibiotics are not optional—they are lifesaving. The evidence is robust, the benefit-to-risk ratio clear, and the guidelines uniform.

When They Are Misused

Yet antibiotics are too often prescribed “just in case.” In some hospitals, more than half of all obstetric patients receive antibiotics at some point during pregnancy, even when no infection is confirmed. Upper respiratory infections (often viral), mild vaginal discharge, or low-grade fevers can trigger unnecessary prescriptions. Some clinicians use antibiotics as reassurance—something to do—rather than a measured response to evidence.

This misuse carries consequences. Antibiotic resistance in obstetric pathogens such as E. coli, Klebsiella, and Ureaplasma is rising. Broad-spectrum antibiotics alter the maternal and neonatal microbiome, which emerging research links to asthma, obesity, and autoimmune disease later in life.

Even short-term overuse in labor wards can cause harm: increased risk of Clostridioides difficile infection in mothers and early antibiotic exposure in newborns that disturbs gut colonization.

The Principle of Stewardship

Antibiotic stewardship in pregnancy is both a clinical and ethical duty. Antibiotic stewardship means using antibiotics thoughtfully and responsibly to protect their power for those who truly need them. It focuses on giving the right drug, at the right dose, for the right reason—avoiding both overuse and undertreatment. The goal is not necessarily to use fewer antibiotics, but to use them better. ACOG, the CDC, and the WHO all recommend targeted prescribing based on:

Clear indication – Is there laboratory or clinical evidence of infection?

Correct drug – Is the antibiotic safe in pregnancy and active against likely pathogens?

Right timing – Is it administered when benefit outweighs risk?

Shortest effective duration – Is therapy continued no longer than necessary?

Amoxicillin, cephalexin, and nitrofurantoin (except near term) are generally considered safest.

Tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones, on the other hand, are avoided due to potential fetal toxicity.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is used only when alternatives are unsuitable.

Stewardship also extends to surgical teams. A single preoperative dose at cesarean is enough; postoperative “just-in-case” antibiotics offer no proven benefit and promote resistance.

The Ethical Responsibility of Physicians and Patients

Antibiotic stewardship is not only a matter of science but also of ethics.

Physicians have a duty to use their knowledge wisely—to prescribe only when evidence supports it and to explain clearly why an antibiotic is or isn’t needed. That explanation is part of informed consent, not a courtesy.

Patients, too, have a role. They have the right—and the responsibility—to ask questions: What infection are we treating? How do you know it’s bacterial? Is this drug safe in pregnancy?

When both sides engage honestly, unnecessary treatment decreases and trust increases. Good medicine depends on shared understanding, not blind compliance. The most ethical prescription may sometimes be no prescription at all.

Learning from Semmelweis Again

If Semmelweis taught us anything, it’s that infection control begins not with technology, but with discipline and humility. He did not have antibiotics. He had evidence and courage. His story reminds us that good medicine is not only about prescribing the right drug, but about asking the right question: Is this truly needed?

A modern “Semmelweis moment” in obstetrics is not handwashing, but accountability in antibiotic use. The stakes are high. The same miracle drugs that once saved millions could lose their power if we fail to respect them.

Lessons for Clinicians and Patients

For clinicians: Follow evidence-based protocols, culture before treating when possible, and resist pressure for unnecessary antibiotics. Discuss risks and benefits transparently.

For patients: Do not demand antibiotics for viral illnesses. Ask your provider why a specific drug is needed and whether it’s safe in pregnancy.

For institutions: Monitor prescribing patterns, support antimicrobial stewardship committees, and educate staff.

Antibiotic use is a moral as well as a medical issue. Each unnecessary dose contributes to the global resistance crisis that threatens everyone, including the next generation.

Reflection / Closing

The arc from Semmelweis to stewardship is a story of progress—and amnesia. We celebrate the fall of maternal sepsis yet forget the discipline that made it possible. In pregnancy, antibiotics should be viewed as sacred tools, not routine conveniences. The ethical question remains: when faced with a worried patient, are we prescribing for her benefit or for our own comfort?