6 Essential Ways to Help Prevent a Stillbirth

What it is, when it happens, and what actually lowers risk.

What a stillbirth is

A stillbirth is the death of a fetus at or after 20 weeks of pregnancy. In the United States it occurs in about 1 in 170 pregnancies, roughly 21,000 cases per year. Most happen in the third trimester, particularly after 32 weeks.

Stillbirth is not a single disease. It is the final outcome of different processes.

The most common is placental failure, where the placenta no longer delivers enough oxygen and nutrients.

Other causes include fetal growth restriction, maternal medical illness, infection, and acute cord events. Importantly, many stillbirths are preceded by warning signs or identifiable risk factors. Prevention in obstetrics therefore means risk reduction and earlier intervention, not the unrealistic promise of zero risk. Stillbirths can still happen despite everything being done correctly.

1. Recognizing decreased fetal movement

The most frequent warning sign before many stillbirths is a change in fetal movement. In multiple studies, a large proportion of mothers who experienced stillbirth noticed their baby moving less in the days beforehand.

Beginning at about 28 weeks, a patient should know her baby’s usual pattern of activity. A sudden quiet pattern, weaker movement, or prolonged time to feel movement should prompt immediate evaluation. A practical method is to lie on the side and confirm that 10 movements are felt within two hours. Failure to reach that, or a clear deviation from the baby’s normal behavior, warrants calling labor and delivery the same day. Decreased movement is a physiologic symptom of fetal hypoxia, not maternal anxiety, and evaluation is simple and safe.

2. Detecting fetal growth restriction

A fetus that is not growing properly is at substantially higher risk of stillbirth, often because of placental insufficiency. The baby may appear normal but is receiving inadequate oxygen.

Routine prenatal care addresses this by measuring fundal height and performing ultrasound when growth is uncertain. When restriction is suspected, Doppler studies and surveillance are used. Detecting growth restriction often changes management and may lead to earlier delivery. This is one of the clearest examples in obstetrics where monitoring directly prevents fetal death.

3. Controlling maternal medical conditions

Maternal disease significantly affects placental function. Diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, thyroid disease, and autoimmune conditions all increase stillbirth risk through placental vascular injury.

Careful medical control lowers that risk. Good glucose control in diabetes, treatment of hypertension, and aspirin prophylaxis in high-risk pregnancies reduce placental complications. Prenatal care is therefore not only observation. It is active physiologic management aimed at protecting placental circulation.

4. Avoiding smoking and nicotine exposure

Smoking approximately doubles the risk of stillbirth. Carbon monoxide reduces fetal oxygen delivery and nicotine constricts placental blood vessels. The effect is dose related and biologically consistent.

The important point is that this applies not only to cigarettes but also to vaping and other nicotine products. Stopping smoking during pregnancy measurably reduces risk even if cessation occurs after the first trimester. Among modifiable factors in pregnancy, this is one of the most powerful.

5. Appropriate timing of delivery near term

The placenta ages. After 39 weeks its function gradually declines in some pregnancies. Stillbirth risk rises as pregnancy continues beyond term, particularly after 41 weeks.

Monitoring in late pregnancy and delivery at appropriate gestational ages reduce fetal death without increasing neonatal harm in properly selected pregnancies. Timing of delivery is therefore a biologic decision about placental function, not a matter of convenience.

6. Maternal sleep position in late pregnancy

Research from several countries shows that falling asleep on the back in the third trimester is associated with increased stillbirth risk. The likely mechanism is compression of major maternal blood vessels, reducing uterine blood flow.

The recommendation is simple and low burden. After about 28 weeks, begin sleep on the side. If a woman wakes on her back, she should simply turn back to the side. No intervention is needed beyond repositioning.

A realistic closing perspective

Not every stillbirth can be prevented. Congenital anomalies, sudden placental abruption, and acute cord accidents still occur even with excellent care. However, evidence consistently shows that many stillbirths are preceded by reduced movement, placental dysfunction, maternal disease, or modifiable exposures.

Stillbirth prevention is therefore based on vigilance, communication, and timely medical action. The purpose of prenatal care is early recognition of fetal compromise while intervention is still possible.

A clear, evidence-based way to monitor fetal movement in the third trimester

Advice about fetal movement is often imprecise. Patients are told to “be aware of movement,” but awareness alone is not a reliable clinical instruction. There is a simple, studied method that can be explained clearly and used at home.

Beginning at 28 weeks, the patient should pick a time of day when the baby is usually active, commonly in the evening or after eating. She should lie on her side, minimize distractions, and focus only on distinct movements such as kicks, rolls, or stretches. Hiccups are not counted.

She then counts how long it takes to feel 10 movements. In most healthy pregnancies, ten movements occur within about 30 minutes and almost always within two hours. The exact speed is less important than the baby’s usual pattern.

The key instruction is this. The patient should call Labor and Delivery immediately if ten movements are not felt within two hours, or if the baby’s activity is clearly weaker or quieter than its normal behavior, even if some movement is present. A sudden change matters more than an absolute number.

The biological reason is well understood. In placental insufficiency, the fetus becomes relatively hypoxic. To conserve oxygen, activity decreases. Reduced movement frequently precedes abnormal fetal heart rate testing and, in some cases, fetal death.

Observational and interventional studies show that structured fetal movement monitoring leads to earlier clinical evaluation. Most evaluations provide reassurance. A smaller number identify compromised fetuses and lead to timely delivery. The intervention itself is safe and noninvasive, and professional guidance supports responding promptly to reported decreased movement.

Clinically, decreased movement should be treated as a symptom, not as maternal anxiety.

Graph A — Reassuring pattern (normal variability 30–60 min)

How to interpret:

Day-to-day fluctuation is normal. The time to reach 10 movements changes, but it consistently stays within a healthy physiologic range. This is what we typically see when placental oxygen delivery is adequate.

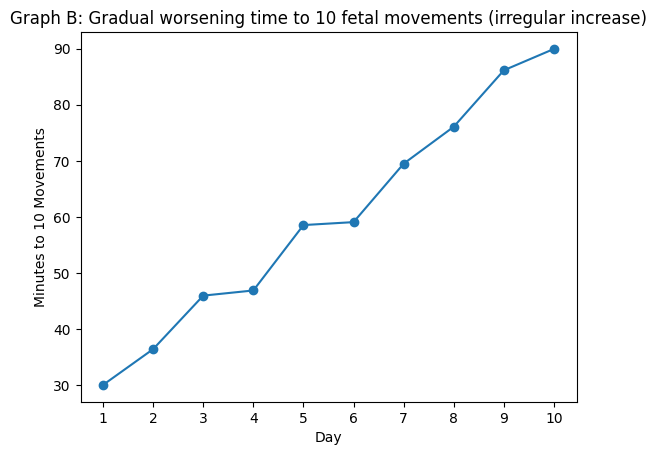

Graph B — Concerning trend (progressively slower movements)

How to interpret:

The baby is still moving, but each day it takes longer to feel 10 movements. This is clinically important. A progressive increase in time to reach 10 movements can reflect developing placental insufficiency. Many stillbirths are preceded by exactly this pattern rather than a sudden complete absence of movement.

Key counseling message for patients

A single slow day may not mean danger.

A trend toward slower movement over several days is a symptom and should trigger evaluation.

How your partner can help

Stillbirth prevention is not only a medical issue. It is also an observation issue. The partner is often the first person to notice behavioral changes in the pregnancy.

A partner can help by learning the baby’s usual movement pattern together with the mother, especially in the evening when activity is easiest to feel. Sitting quietly together for a few minutes and asking, “Is the baby moving like usual today?” is not trivial reassurance. It is a form of monitoring. If the mother is unsure, the partner should encourage lying on the side and focusing on movements, not dismiss the concern.

Partners also play an important safety role in decision making. Many mothers hesitate to call the hospital because they worry about bothering staff or being told everything is fine. A partner should actively support contacting labor and delivery the same day if movement seems decreased or clearly different. Prompt evaluation is appropriate care, not overreaction.

Finally, partners can help by supporting medical recommendations that protect the placenta, including smoking cessation, keeping appointments, and attending visits when possible so that warning signs and instructions are understood by both parents. In several studies of delayed presentation after decreased fetal movement, hesitation and reassurance at home contributed to late evaluation. The practical message is simple. When in doubt, the partner should help escalate concern, not minimize it.

References

Stacey T, Thompson JMD, Mitchell EA, Ekeroma AJ, Zuccollo JM, McCowan LME. Maternal perception of fetal activity and late stillbirth risk. BMJ. 2011;342:d340. doi:10.1136/bmj.d340. PMID: 21273389.

Winje BA, Saastad E, Gunnes N, et al. Fetal movement counting and stillbirth prevention. BJOG. 2016;123:2079-2087. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13818. PMID: 26846771.

ACOG Committee Opinion No. 828. Indications for outpatient antenatal fetal surveillance. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e177-e197. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004407. PMID: 33831926.